![]()

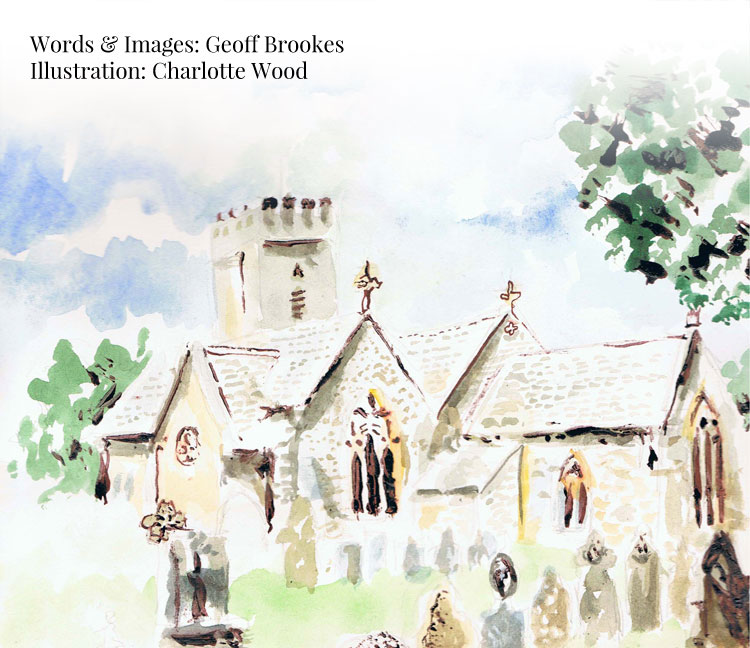

There is a sense of ancient history about St. Llawddog’s church in Cilgerran in West Wales…a sense of forgotten stories…of secrets.

To find Cilgerran you should leave Cardigan on the A478 towards Narberth and turn left into the town. It is a pretty place, with a dominant and picturesque Norman castle standing above the river Teifi. It has always been an important market centre, gathered tightly about the protecting castle. Today, tourists come and enjoy the coracles and the atmosphere of a small town connected to its past.

As you enter the High Street, turn immediately to the left and follow the road round and down, and it will bring you to the church of St. Llawddog. It is surprisingly well ordered. The churchyard has been tidied considerably, and the stones in the older part are placed in neat rows. This happened during restoration work in 1836 when, sadly, Thomas Phaer’s grave disappeared. There was a lot of tidying to do. The building had been there for a long time and had become dilapidated. The church was probably there in the 6th century and the earliest written record of it is from 1291. It is a church that Thomas would have known very well and it is where his gravestone was once a respected feature.

Another older stone was preserved, however. A megalithic standing stone is here, upon which Ogham script was carved; there are short and long notches along the edge, a form of writing used by the Irish and dating back to the 6th century. Such stones were often erected over the graves of chieftains.

This one says: “Here lies Trenegussus, son of Macutrenus.”

Turn left outside the vestry and you will see it, standing like a piece of rock that has fallen randomly from the sky, in the second row. It has an air of mystery. It makes you feel quite small to confront such a message from so long ago.

We were there in search of Thomas Phaer – writer, magistrate, customs searcher and Commissioner for Piracy. Oh yes, he packed a lot into his fifty years. And, he should be remembered not only for these things but, most importantly, for his work, ‘The Boke of Chyldren’, the first book in English on childcare.

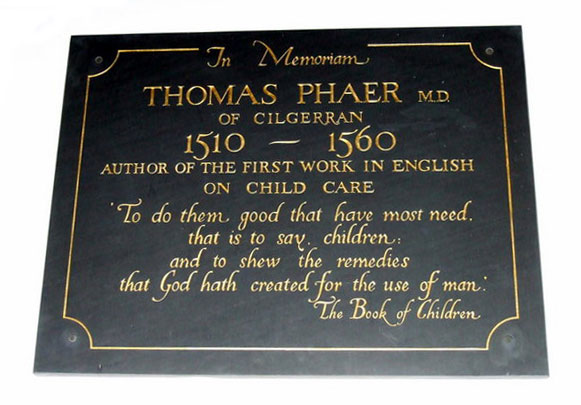

There is a memorial to him on the left-hand side on the wall of the church as you approach the altar. It carries a quotation:

“Thomas Phaer M.D. of Cilgerran 1510 – 1560

Author of the first work in English

on child care.

To do them good that have most need,

that is to say, children:

and to shew the remedies

that God hath created for the use of man.

The Book of Children.”

The plaque is an apology for the disappearance of his tomb, and was installed as a result of donations from national and international medical societies, because Thomas Phaer is a very significant figure, a pioneer of paediatric medicine.

It is hard to piece together accurate details of a life lived long ago, a life which was largely unrecorded. But we do have some significant details. He was born in Norwich, perhaps in 1510, to Thomas and Clara. The family had Flemish origins. He was a highly educated man, attending Oxford University and then Lincoln’s Inn. He followed a highly successful legal career.

The key moment in his life was when he became Solicitor to the Council of the Marches and settled in Cilgerran. He married Anne, daughter of Alderman Thomas Walter of Carmarthen, and lived at Fforest farm, where they had three daughters: Eleanor, Mary and Elizabeth. Thomas was a JP and Member of Parliament for Cardigan, and he devoted himself to his extensive official duties.

In 1551, he surveyed the coast of Wales for Edward VI. He wrote, “All along this coast is no trade of merchandise but all full of rocks and danger.” It was an isolated, largely unknown place at this time. He became Customs Searcher and, later, Commissioner for Piracy – because, no matter how wild West Wales appeared, there were always those ready to exploit its remoteness.

But, he combined his work with other things, particularly with writing. His first book was a legal work and he was also known as a highly regarded translator. He was especially well known for his translation of Virgil’s Aeneid, which remained the standard version of the text for almost 150 years.

Perhaps it was this interest in translating ancient texts that inspired the medical writing upon which his reputation is based. Medical practice then relied upon ancient texts written by Galen and Avicenna, and had thus largely remained unchanged for some considerable time. Thomas Phaer translated a poem called ‘Regimen Sanitatis Salernitanum’, which was, unusually, a medical poem written in this form to make it easy to memorise. He called his translation ‘The Regiment of Life’, and in 1545 he published an addition to the work which was called ‘The Boke of Chyldren’.

This was a highly significant moment and the book became extremely popular, running to several editions until 1596. It contains 40 diseases with “remedyes” in each case, including “bredyng of teeth” and “pyssyng in bed.” The book recognises children as a special class of patients, often ones who cannot explain, precisely, their symptoms. He made a clear distinction between adulthood and childhood. He considers “manye [many] grievous and perilous diseases” in his book. So, you will find references to “apostume of the brayne” (meningitis) and “terrible dreames and feare in the slepe” (nightmares).

In 1559, he was awarded a Bachelor of Medicine Degree from Oxford and then a Doctorate, after having practised medicine, by his own admission, for twenty years. That level of experience is underlined by the strong thread of practicality that runs through his book. Of course, some of what he writes is rooted very much in the times in which he lived, and opens a fascinating window into his world. In this way it is a valuable record of social history. For example, he says “Stifnes of limes which thing procedeth many tymes of cold, as when a chylde is found in the frost, or in the street, cast away by a wyked mother.” And, whilst accidents in the home are as important now as they were then, few of us today would say that the major cause of ulceration of the head is from sides of bacon or salt beef falling from hooks in the ceiling!

As we can see, Thomas Phaer was writing at a time before spelling became standardised; you can see this in the different versions of his name: is it Phayer, Phaer or Phaire? There is certainly great pleasure in reading what he has to say, because it seems so quaint. But, never underestimate the informed good sense that his words contain. He speaks, for example, about how parents should avoid elaborate cures:

“Of small pockes and measilles the best and most sure helpe in this case is not to meddle with anye kynde of medicines but to let nature work her operacion.”

This is obviously not something that doctors would like to hear, but it was undoubtedly the best advice available at the time.

His book contains references to antibiotics made from mould, using “the musherom called iewes eares.” He includes several medicines to kill lice, including: “Take mustered and dissolve it in vinegre with a lytle salt peter, and anoint the place where as the lyce are wonte to breede.” There are some modern-sounding practices too. He writes about postural drainage: “Of the cough it is good nowe and than to presse his tong with your finger, holding downe hys head that the reumes may issue…”

Part of his mission was his desire to make medical advice accessible, to move away from the Latin that was normally used to obscure and preserve a mystique. This is clearly why his work was such a popular one. He offered reassurance and knowledge to parents who, just like ourselves, would suffer serious anxiety whenever one of their children was unwell. It goes to show that, whilst times change, people stay very much the same.

He was a great and influential man, and it is such a pity that we no longer have his grave to honour.

When Thomas died, in the autumn of 1560, his neighbour George Owen said of him that he was a “man honoured for his learninge, commended for his governmente, and beloved for his pleasant natural conceiptes.” We remember him still, 500 years after his death, a sure sign of the great influence his productive life had upon others.