![]()

This is a grave that either contains mysteries – or contains nothing at all.

It is simple and unassuming, close to the wall of the parish church in Caio in Carmarthenshire. It is the grave of John Harries (interred with his father) who, together with his son, Henry, became known as the dynion hysbys (cunning men) of Cwrt y Cadno. They achieved considerable fame and notoriety in the early nineteenth century. And whilst the gifts were allegedly shared by many in the family, John (1785-1839) and Henry (1821-1849) were the most notable exponents of the dark arts.

The family lived at Cwrt y Cadno at Pantcoy in the Cothi valley. John and Henry, his son, received a conventional education. They both went to Haverfordwest Grammar School. John trained as a surgeon, probably in Edinburgh. He then practised in Harley Street, interestingly with an astrologer called Robert Smith, also known as Raphael. Henry later attended London University and the Royal College of Surgeons.

When John returned to the Cothi valley he used an unusual combination of conventional training and traditional remedies in his practice. Anxious people came from far and wide to consult him on matters involving healing (both human and animal), fortune-telling and prophecy, much of the work undertaken with the aid of astrological projections.

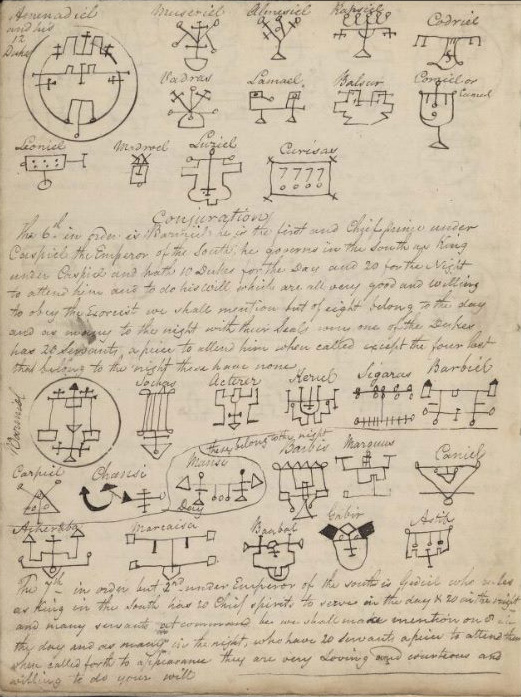

These were superstitious times. Any sort of learning or knowledge had a mysterious quality. In a semi-literate society, book ownership was not very widespread. Most homes would contain only a Bible. John Harries had an extensive library of medical books and various Latin and Greek texts. A library was dangerous, something to be feared, full of unknown things. And these things gave the Harrieses huge power. Belief in witchcraft and magic was commonplace. Urban society might scoff and embrace all those scientific and technical advances that changed nineteenth-century life, but out in the country the old beliefs persisted – and Caio in the Cothi valley was remote.

It was believed that the Harries family derived its powers from a large padlocked book of spells, bound in iron. The book, if it ever existed, has been lost – though most believe that it was in fact merely a case that held surgical instruments. But people believed in them because they wanted to, because they wanted simple answers to complex problems. They believed that Harries could intercede for them and call down solutions from the supernatural world.

They were seen as charmers and healers, who could stop bleeding, heal wounds and cure skin disease whilst restoring mental balance. I wouldn’t mind an appointment myself! They promoted their ability to influence both the mind and body of their patients. They promoted the use of fresh spring water as a cure for most things.

As John Harries’ reputation spread, people came from all parts of Wales to consult him. It is claimed that he had a particularly successful approach to mental disturbance. He used three different approaches to effect a cure: the herbal treatment, the bleeding treatment and, of course, the water treatment; this involved taking the poor afflicted person to the edge of a river and firing an old flint revolver behind them so that, startled, they would fall into the river. The concept of ‘For goodness sake, pull yourself together!’ had its pernicious hold in rural Wales even then.

The division between religion and superstition became blurred. Everyone went to church, accepted the concept of demonic possession and still believed in witchcraft. One man who came to see Dr John was convinced that he was bewitched. He had had numerous treatments from other doctors, with no effect. Harries abused the family for taking him to see quack doctors and said that, obviously, the problems had arisen from swallowing an evil spirit in the shape of a tadpole which had grown into a frog. He consulted his books and called upon the spirits, which made the patient vomit – and yes, you are right, there amongst the vomit was a frog.

It was particularly the claims made that they could predict the future, recover missing property and consult with the supernatural that brought father and son notoriety. Henry was not one to shy away from publicity. He promoted his ability to determine:

‘… what places best to travel in or reside in, what trade or profession best to follow, and whether fortunate in speculation, viz: lottery, dealing in foreign markets, etc’ services which, sadly, my own general practice does not currently offer.

He claimed to be able to determine whether marriage would prove happy or otherwise, and whether children were born lucky or not, from the planetary orbs at the time of birth. Such knowledge did not help him, however. Henry married Hannah Marsden in the face of some hostility from his family. He was felt to be marrying beneath him, for she was the daughter of a local workman in Caio, but he told everyone that he had no choice. Their union had been pre-ordained in their astrological charts. Sadly it was not a happy marriage. Perhaps he had missed that part in the stars.

It was also said that after John’s death in 1839, Henry tried to contact Raphael about consulting his father in the spirit world – which in fact was far more difficult than he realised, since Raphael had died eight years earlier.

Stories gathered around them. One of the most famous cases involved a local girl who had disappeared. Dr John was consulted and he immediately told the family that she had been murdered by her lover. He told them where the body was buried, near Maes yr On, under a tree with a bees’ nest, next to a stream. And of course they found her. Her lover confessed. But the magistrates called Harries before them. Clearly he knew too much. Perhaps he was involved. So he was charged with aiding and abetting. How else could he have known? His defence was based upon his ability to predict the future. He promised the magistrates that, if they would tell him the hour of their birth, he would tell them the hour they would depart from this world. They quickly set him free.

People would travel on long journeys to see him, to discover the whereabouts of their lost cattle, for example. After a fruitless search, a woman sought advice from him about her lost wedding ring. On her arrival and before she could speak, Dr John told her that a relative would return it. On her return home her son returned the ring and expressed his regret and relief that he could now die in peace, as he did, two days later. Stories about Dr John using his gifts to recover lost spoons perhaps suggest a certain wasting of talent.

But even their revelations were to be feared. An old man sought their help to recover money he had lost. Harries promised that he would certainly get his money back and that the thief would be punished by being bedridden. Good news for the old man. Revenge is always sweet – except that the money had been taken by his wife. She took to her bed and remained there for eighteen years.

The doctors generated their own mythology and promoted an image they were happy to exploit. They would end their bills with: ‘Unless the above amount is paid to me … adverse means will be resorted to for the recovery.’

Sceptics might say they gulled the credulous for many years and reaped a bountiful harvest, but for many the Harries were not men you would wish to have as enemies. They inspired fear and compliance.

And yet no matter how good the physician was he could not protect himself. Henry’s health was delicate. He died of consumption in 1849, aged twenty-eight.

As for his father, it is said that Dr John saw his own death written in the stars. It was apparently booked in for 11th May 1839. To avoid his fate, John took to his bed for the whole day. However, the house caught fire. He ran downstairs and went up a ladder to throw water on the roof. The ladder slipped and he fell and was killed.

His body was taken to Caio and as the bearers approached the churchyard the coffin suddenly became lighter. This was because the Devil took possession of Dr John’s body, just as he had previously taken possession of his soul.

Obviously.