Thomas Johnes had a mad idea, that you could tame and order a landscape as wild and extensive as the Ystwyth Valley. Like others he believed that human intervention could improve what nature had created. But the Hafod Estate, no matter how beautiful, was always a wild and unsustainable dream.

You can find the estate on the B4574 in Ceredigion as it leads away from Devil’s Bridge. It was once owned by the monks of Strata Florida, but with the dissolution of the monasteries it passed into the ownership of the Herbert family, who were interested in exploiting the timber and the mineral resources.

Feature image: Eglwys Newydd Church (also known as St Michael’s Church, Hafod)

Thomas Johnes was born in Ludlow in 1748 and educated first at Eton and then at the University of Edinburgh. He became an MP; he took a military commission. But his life changed on a visit to the family property at Hafod which became his through inheritance. He was captivated by the estate. He wrote to a friend to tell him that he had found paradise. Hafod became a passion that never left him.

His first wife Maria died in 1782 within a year of their marriage. He then married his cousin, Jane Johnes, in the face of considerable family disapproval. Together they took up residence at Hafod and in 1784 their only child, Mariamne, was born.

They built a mansion designed by Thomas Baldwin of Bath and the building was finished in 1788. It was built in Bath stone, which glows in the gentler climate along the Avon but the soft stone was not a wise choice for driving Welsh rain. It weathered quickly.

In 1793 he employed the architect John Nash, to add a library and a conservatory. It was a grand building, sheltering in its green valley and was painted by Turner, one the many famous figures who was drawn to the estate. Coleridge is said to have based the ‘pleasure domes’ of Xanadu in his poem ‘Kubla Khan’ upon the shape of the Hafod building that stood in the valley below him when he came to visit. The house was regarded as ‘one of the most attractive and admired seats in the principality’ and was noted for its library. It contained a printing press and produced literary texts, particularly of French Chronicles from the Middle Ages, about which Johnes, a noted translator, was something of an expert. Every effort was made to create a cultured environment that reflected the very best of human achievement.

Johnes was clearly a benevolent man and devoted his energies to the estate and its people. He built cottages, employed doctors and started a school for girls. His influence was everywhere. Over a period of five years more than 2 million trees were planted. He certainly brought employment to the area as he tried to carve something out of the wilderness. The estate was designed to be enjoyed on foot, providing an enormous variety of experiences. His intention was to provide sketching stations where the privileged could stop and sketch the views that lay before them.

His visitors stayed either at Hafod itself or in the Hafod Arms at Devil’s Bridge, which was built for the purpose. From there they would travel up to the estate to look at the interior of the house, the kitchen garden and then they would follow the paths until it was time to go home, admiring ‘majestic mountains and romantic rocky precipices, rivers foaming in cataracts’.

Yet the whole project was dogged by fire, destruction and tragedy.

Whilst Thomas was away in London, the house was destroyed in a fire in 1807 which ‘broke out early in the morning; and, with the exception of a very small portion of the books rescued from the flames by the intrepidity of Mrs. Johnes, the whole of the library, consisting of many thousand volumes, several of the paintings, and nearly all the splendid furniture of the house, were consumed.’ Jane and Mariamne then watched the destruction of their home from a hill on the estate. What an awful sight it must have been, with the flames lighting up the vast darkness of the valley.

The house was re-built by Baldwin again, at great expense, but the drain upon the estate was immense and it was funded largely by the sale of timber. But the greatest tragedy of all was Mariamne. She was very intelligent and she had a great interest in the natural world. She was educated by tutors, who taught her music, drawing and languages but it was botany that was her greatest love and from an early age she corresponded with the leading naturalists of her time. But there was a problem. When she was 10 years old she became chronically ill. There have been a number of subsequent diagnoses, which have included tuberculosis and congenital syphilis. Certainly she was very ill. She suffered from tumours and curvature of the spine and required a steel brace to support her. She never married and died suddenly in 1811, aged 27, on a visit to London and in some ways Johnes’ purpose disappeared with her. Yet in 1810 everything was possible. He built an arch over the road at the highest part of the estate to mark the golden Jubilee of King George. But Mariamne’s death tore the heart out of the family and all the energy that had maintained the estate suddenly dissipated. It was too great a task and the money was running out.

In 1815 the Johnes moved to Dawlish and Thomas died a year later in April 1816. Paradise had made him bankrupt. It had absorbed his time, his energy, his money and then destroyed him.

It was sold for £70,000 to the Duke of Newcastle in 1833. He was a highly unpopular owner but he made one significant contribution to the sad history of Hafod. The Johnes family had commissioned a statue of their beloved Mariamne from the great Victorian sculptor Francis Chantry. But Johnes was unable to pay for it and it remained in London until the Duke settled the bill and moved it to Egwlys Newydd on the estate.

Johnes replaced the original church on the estate in 1801, with something far more elegant, designed by James Wyatt who restored Salisbury Cathedral. Behind the church there are the railings which surround the Johnes family vault. Within it lie the remains of Thomas, Jane and Mariamné, absorbed into the soil to which they devoted their lives.

Chantry’s sculpture within the church brought many to see to it and yet this too was hunted down by tragedy. In April 1932 the church, which had just had a new heating system, caught fire. The nearest telephone was at Devil’s Bridge and by the time the Fire Brigade arrived from Aberystwyth, the roof had already fallen in. Their jets of water, cracked the overheated marble of the statue. It shattered into fragments.

It is still there, a suitable symbol for the failed project that the Hafod estate became. A thing of beauty that time has taken away from us. It is the final tragedy of the Johnes family. The vicar told me it would cost too much to have it properly restored or replicated, so it still sits there, forlornly speaking of sorrow rather than art.

The estate was owned by a succession of timber merchants. But it seemed to need more money than it could generate. Where once it was the most visited place in Wales, it became lost and forgotten and by 1946 it was declared derelict. In 1958 what remained of the mansion was demolished by explosives as a health and safety measure.

The ruins are still there. You can scramble over them as I have and you can see features appearing through the rubble – a brick arch, a cornice.

The Hafod Estate Trust is now helping the estate to re-emerge from beneath the tangled embrace of the rhododendrons and the undergrowth. You can take fantastic walks through the estate, with different levels of difficulty. (The Gentleman’s Walk. The Ladies Walk) the walks are now tamed and clearly marked but they remain wild and isolated. You can find yourself down the river and suddenly think you are in Alaska.

Mariamne’s garden is slowly emerging too. We know now that the garden paths were originally made from crushed quartz, which would have sparkled so much in the sunshine.

Another thing that we have lost.

Words: Geoff Brookes

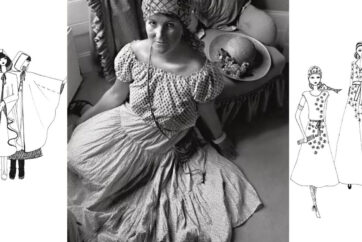

Illustration: Charlotte Wood