![]()

As you drive the short distance out of Merthyr to Vaynor, the scenery changes in an instant. Suddenly, you are on twisting country lanes that lead into the rugged hills of the Brecon Beacons. It is so different from what you have left behind, namely the industrial wasteland that Merthyr became. Even the Crawshays in their grand castle would have recognised this.

It is a journey the Crawshay family would take to this pretty little church every week, for it is not far up the valley, only four miles. A pleasant walk, or ride if it rained, from their grand home in Cyfarthfa to church: green, isolated, timeless, the air fresh and pure.

You arrive at St Gwynno’s church in a place that is completely separated from that world of poverty, suffering and disease. But not death. Of course not. That comes to everyone. We mark it in different ways, that’s all. You can see this in any cemetery.

You will find his grave in a prominent position inside St. Gwynno’s Churchyard. It is so huge that it is impossible to miss. It is surrounded by iron railings to the left of the church as you enter the churchyard. The slab is tinged with encroaching moss. It is monolithic, alien. Thirteen horses dragged it twenty miles from the quarry at Radyr. Eleven tons of granite put there, some say, to prevent his soul from rising up at the Resurrection. No, he was not a popular man.

It was never intended that Robert Thompson Crawshay should become an Ironmaster, but the death of his brother, drowned whilst crossing the River Severn at Beachley, pushed him into adopting a role for which he was wildly unsuited. He suddenly inherited the family business from his father, the charismatic William Crawshay.

A journey began from success to failure. Under Robert’s leadership, the Cyfarthfa ironworks entered a long and terminal decline. Already, the local iron ore deposits had been exhausted and they began to rely on imports. The business required far more energetic leadership and business acumen than Crawshay could provide. His interests and his problems lay elsewhere, because you could never really say that he was a happy man.

His family had been at the heart of the unimaginable changes that had transformed Merthyr. It had once been a small village, home to farmers and shepherds. But, then came the rapid and uncontrolled expansion fuelled by the accidents of geology: the iron ore, the coal, the limestone deposits.

Suddenly, the town had grown far beyond the capacity of the area to cope. The gentle pastoral life on the edge of the Brecon Beacons disappeared, to be replaced by a vision of hell. By 1801 it was the largest town in Wales. Thousands were drawn there by the possibility of regular work, and there was plenty of it. Merthyr was an important place, doing important work. The town provided the materials that defeated Napoleon, but at considerable cost. There had never been either adequate water supply or sanitation systems to cope with a population of 40,000. Space was in short supply and houses were crammed closely together, built quickly and cheaply. Water was collected from pumps in the street or from the polluted River Taff. Cholera was rife. In 1849 over 1,400 people died of the disease. Infant mortality was high. ‘Some parts of the town are complete networks of filth, emitting noxious exhalations,’ said a report in 1844.

Whilst the Crawshays and the other ironmasters brought employment and prosperity for some, they were responsible too for squalor and death. Wales, the first industrialised nation on Earth, was built upon foundations of overcrowding and disease and the suffering of the weakest. At the top of the pyramid, though, were the Crawshays. Their home in Cyfarthfa was an incongruous island of gentility in this poisoned land.

You cannot visit Cyfarthfa Castle as it is now, without being aware of the tremendous contrast that must have once existed: the grand house, the style, the chandeliers, the staircases and the panelling. It gives the impression of an ancient family seat. A very short distance away, their employees lived in degrading squalor. The majority of the elegant residence was built by Richard Lugar, in only twelve months at a cost of £30,000 in 1824. It is a house of 365 windows, of gardens and hothouses. It was built to overlook the successful ironworks, looking down proudly upon the foundation of their wealth.

Today, it is an interesting museum. Then, it was a symbol of power, a self-contained community that emphasised their prosperity and position. But people died to keep the Crawshays living in such splendour.

Steel began to supersede iron, but Robert was unwilling to take up its manufacture. Bessemer Converters were too expensive. He would not invest in the new process; so his works were left behind and others took their business. They would never win it back. The success carefully nurtured by his father and grandfather would never return to Cyfarthfa and Robert’s interests lay elsewhere.

In 1846, Robert married Rose Mary Yeates, just before her 18th birthday. She was a well-connected and cultured young woman, acquainted with Darwin and Browning. However, the marriage did not prosper; he was a complex person and never truly happy, she was ambitious and energetic, with a strong belief in the role and status of women.

No compromise. No meeting of minds. They drifted apart and Rose Mary eventually spent most of her time in London. Initially, Robert was not entirely divorced from the community. He began the Merthyr Horticultural Society; he helped establish schools. He particularly enjoyed music and founded the celebrated Cyfarthfa Brass Band; it was founded largely for his own pleasure, so he always ensured that they had the best of everything. But outside of his private and enclosed world, his workers lived in poverty and filth. Certainly, his reputation amongst his workforce swung wildly between hatred and affection. They never knew what to expect of him. Nothing about him was ever straightforward. He rebuilt St Gwynno’s Church in Vaynor on condition that parishioners helped towards the costs of rebuilding Cefn Coed church on the northern edge of Merthyr. Why did he do this? Vaynor was his church; he worshipped here; he had huge amounts of money and he could afford to restore it; yet, he had to make some sort of point.

Eventually, Robert Crawshay became alienated from his workers. His unwillingness to invest in steelmaking processes damaged the business and impacted on wages. Threats of strike action and unionisation led him to close the works for a time in 1875. He failed at home and at work. An authoritarian figure, inflexible and ultimately lonely, his very authority was questioned and rejected by those he believed should merely obey; and when they rejected his authority, they rejected him. The plight of his workers and the contrast between their hardships and the comfortable luxury of the Crawshays provided the perfect conditions for the growth of valley socialism. It was not only the physical landscape that the Crawshays changed; it was also the political landscape.

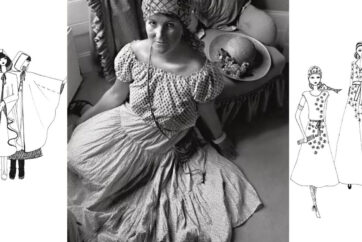

A stroke in 1860 left Robert Thompson Crawshay profoundly deaf. He replaced music with photography and left a legacy of important and historic pictures. He was dedicated to this enthusiasm, investing heavily in new equipment. He had a studio constructed in the castle and a travelling hut that he would take with him to locations in the Brecon Beacons. But, his favourite subject of all was his eldest daughter. When his wife retired to London, his life became focused upon Rose Harriette. He had her pose in exotic costumes, often dressed as a member of the picturesque poor; they were just like rich people, except that they had less money and certainly they lived in fewer rooms than the Crawshays, but they were fragrant and clean.

The real poor were just a little way away from Cyfarthfa but dealing with them was more complicated. They were far less attractive and certainly less tractable. Rose was made to process the films. Robert, it seems, believed that his enthusiasm should be hers too. She was less impressed. This is an extract from her diary, 23 March 1868:

‘Washed a lot of prints, got 3 fresh chilblains; really what with chilblains and chaps from the coldness of the water washing prints and the stains from all the chemicals all over my hands, they are not fit to be seen. It is too bad. I don’t believe another lady in the kingdom has such hands’.

He possessed her and could not conceive that she could ever desire a life separate from his own, and when he had to confront what the rest of us would regard as inevitable, his response was unpleasant and unreasonable. In his portraits he looks a stern man, hard, inflexible, certainly thoughtful and perhaps troubled. He has a heavy beard. There is a distant look in his eyes. Is he a man carrying a burden, a sense of guilt?

Some people would like to think so. They are encouraged by the epitaph he wrote for himself. Finally, they say he showed remorse for the misery his family had inflicted across the generations.

Carved upon that enormous 11 ton granite slab that marks his grave in Vaynor are the words:

God Forgive Me.

Yet it is an enigmatic epitaph. Forgiveness for what?

See into it what you will. Many have already done so. A final repentance for the sins inflicted upon the working classes? An admittance of his role in creating the hell on earth that was Merthyr?

If only it were so clear cut.

Rose Harriette had once promised her father that she would never leave him: the promise of a child. But, on 23 May 1877 she met local barrister Arthur Williams. When she did leave to marry Arthur, her father exacted a spiteful revenge. Her entirely natural desire for marriage, he regarded as a personal betrayal. He refused to attend her wedding. He added a codicil to his will, disinheriting her children. We may read remorse into the epitaph, but it isn’t necessarily there, for he didn’t subsequently change his intentions. He left things exactly as they were in the material world, with no inheritance for his grandsons. He then asked God to forgive him in the afterlife.