Outside the castle in the heart of the lovely town of Kidwelly, you will find a fine Celtic memorial, unveiled by Gwynfor Evans in 1991. It stands there defiantly, as if confronting the bulk of the Norman castle before it. This memorial represents a fascinating and unexpected story, even though it happened so long ago, at a time when history and myth are almost impossible to separate. Because this is the story of Gwenllian, our very own fighting princess.

The myth tells us that she was a warrior, Wales’ own Boadicea, a beautiful wife and mother, cut down too soon, who died defending her people. The perfect flower of a perfect race, assassinated by cynical, leering foreigners, swinging her severed head by her beautiful bloodstained curls, a brutal death which has always represented the oppression and the subjugation of the Welsh. But she was never just a symbol. She was a real person, living in difficult and brutal times.

After the defeat of the English at the Battle of Hastings in 1066, the Normans spread unchecked across the whole of the country, pushing ever further westwards and on into Wales. For them this was a wild land – remote, mountainous, threatening, sadly the Welsh, typically perhaps, could find little unity amongst themselves with which to face a common enemy. For victory, the Normans needed to do very little, other than to ensure that the Welsh continued to disagree with each other. Any minor victories the Welsh had were always temporary ones and slowly they were pushed out and replaced. The Norman presence slowly but inevitably changed parts of Wales forever.

This is how nations are truly defeated; their culture is destroyed or driven underground. It happened in Wales when Flemish settlers were granted land, particularly across the south, which loosened the grip of the Welsh on their own country. The clock could never be turned back.

There were rebellions, with brutal attacks and brutal reprisals. But only unity could effectively confront the invaders and Gwenllian was the means by which just such an alliance between north and south was briefly created.

Gwenllian was the youngest daughter of Gruffudd ap Cynan, the king of Gwynedd and she married Gruffudd ap Rhys, the son of Rhys ap Tewdur, king of Deheubarth, in modern-day Carmarthenshire. It was a political alliance but also, so legend has it, a love match too. She was born on Anglesey at Aberffraw in 1097 and spent much of her childhood in political exile in Ireland. She was born into politics, into a family of Vikings and Irish kings. There are those who believe that she was a tomboy, with long blonde ringlets, who joined with her brothers in military training. Of course this is complete conjecture, fanciful myth-making that goes way beyond the historical record. No one can ever know.

But over time, the myth of Gwenllian has been enriched by so many romantic images. They say she eloped with her lover, the charismatic Gruffudd ap Rhys, after he travelled north to meet her father. This part might be a romantic embellishment but it was certainly a politically astute union, bringing together north and south.

They lived initially at the family home in Dinefwr and they had to fight to maintain their position. Gruffudd ap Rhys’ success and reputation grew in.attacks on Carmarthen and Kidwelly, especially since he re-distributed the wealth within the towns to the local people. But a serious defeat at Plas Crug just outside Aberystwyth sent the family into hiding in the hills and the forests.

Her name became a rallying

cry throughout the great rebellion of 1136. “Revenge for Gwenllian” was a chant that accompanied the sacking of Aberystwyth castle by troops lead by her brothers.

The unexpected death of Henry 1 in 1135 brought about a confused and chaotic succession. Would it be Stephen or Matilda? The response to this in Wales was the great revolt of 1136.

It began in the south with the defeat of the Normans at Penllergaer, on the edge of Gower, and it soon spread throughout Wales. Perhaps this was the moment they had been waiting for, when they could drive out the invaders.

Gruffudd went north to meet with his father-in -law to plan their strategy, leaving Gwenllian behind. At this moment, reinforcements for the Norman troops in Kidwelly Castle under Maurice de Londres, landed in Glamorgan and advanced westwards.

Gwenllian, with her two youngest sons Maelgwn, 16, and Morgan, 18, led out a force to intercept them. This is the only known example of a medieval woman leading an army of Welshmen into battle.

They marched secretly through the forest of Ystrad Tywi to Kidwelly and camped two miles upstream alongside the river Gwendraeth, at the foot of Mynydd y Garreg and waited. She sent out detachments to intercept the re-inforcements.

Legend has it however that they were betrayed by a local called Gruffudd ap Llewelyn. In such fragmented and uncertain politics there was always treachery. It was in truth always going to be difficult. The Welsh were completely out manoeuvred. Not only did the Normans evade the Welsh detachment but also they circled around the encampment and took up a position on Mynydd y Garreg. They attacked at speed down the hill, whilst Maurice advanced from the castle.

Gwenllian was trapped with her back to the river and the remnants of her army were quickly hacked to pieces. It is believed that Maelgwyn was killed when he threw his own body in front of his mother to protect her. Morgan was wounded and captured. He could only watch as Gwenllian was taken prisoner and immediately beheaded.

The field where it took place is known as Maes Gwenllian, a small piece of flat land between hill and river.

It was a brief and a bloody encounter, entirely successful as far as the Normans were concerned, and of no more importance than so many others. The victors write the history after all. But for the Welsh the death of Gwenllian had much greater significance. She became a nationalist symbol. The warrior princess fighting for her family and her country. There were legends, of course. A spring welled up on the spot where her head fell. Her headless ghost haunted the battlefield looking for her missing head. She only found peace when her skull was recovered and buried. An oppressed people needed a romantic heroine. But it is unlikely that she ever was what the myths say, “A queen of the Amazons”, riding out at the head of an army.

Her name became a rallying cry throughout the great rebellion of 1136. “Revenge for Gwenllian” was a chant that accompanied the sacking of Aberystwyth castle by troops lead by her brothers. Her name remained a badge of identity for centuries after her death.

But history moved on. Her father and her husband both died in 1137. Her story soon only survived in an oral tradition, passed on by the travelling bards in the distant valleys where the Welsh survived, in opposition to Norman rule. And although it was Norman culture which represented the future, outside their castles an older culture survived, believing in symbols and portents, waiting for the spirits of King Arthur and of Merlin to arise from their slumbers and drive out the invaders, crying out, perhaps, “Revenge for Gwenllian!”

She became part of their common heritage, a part of the stubborn individuality and identity of the Welsh, always ready to defy the odds.

As a symbolic figure her name carried more weight with our ancestors than it does generally today. She features in the ancestral line of the Tudor line of the present Royal family, but with little recognition. She is just a name, with little of the significance that she once possessed.

But she is remembered in Kidwelly. Hers has always been a popular name there, and is remembered in the quieter lives that are remembered more conventionally in the churchyard. There is a school in her name, a street – Llys Gwenllian – a Community Hall, a hotel. And a farm with the field in which she died.

The site of the battle is a little way upstream along the Gwendraeth river that curls around the foot of the castle. It is just a field now, green and marshy, where a mother and a son died and a legend was born, and then slowly forgotten.

Words: Geoff Brookes

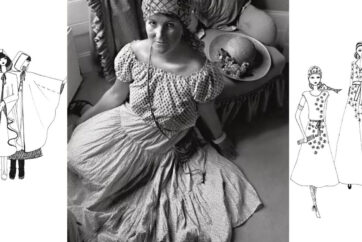

Illustration: Charlotte Wood

First published in Welsh Country Magazine May-Jun 2019