![]()

The graves that symbolise a moment of shame stand clean and bright. They are a mute but significant reminder of one of the darkest moments in Britain’s social history. Leonard Worsell’s grave stone announces – “Workers of the World Unite”. John “Jac” John’s says, rather more pointedly, “Shot by the Military.” Simple words which tell of a moment everyone did their best to forget. We are in the Box Cemetery and these are the graves of the victims of the Llanelli Riot of 1911.

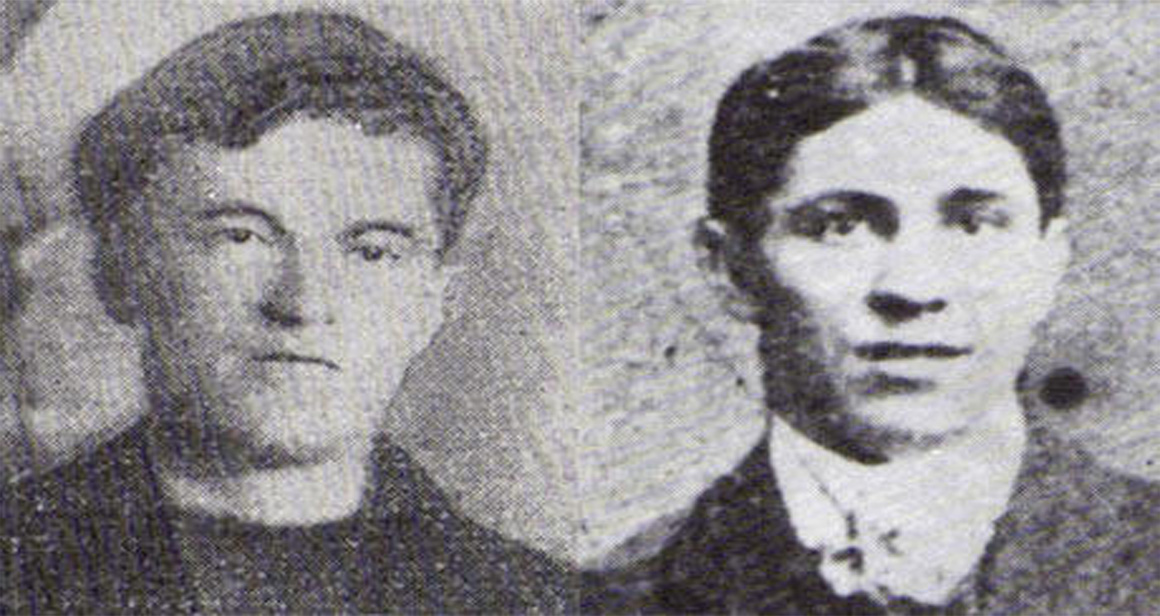

The National Railway Strike of 1911 was an expression of serious grievances about pay. Average wages on the Railway were £1 a week – 20% below those of skilled workers elsewhere. In an act of solidarity, the railwaymen were supported by miners and tinplate workers who received much better rates of pay themselves. One of these was John “Jac” John, who was 21 years old and a millworker at the Morewood Tinplate works. Like all young men who have ever lived in Llanelli, he was described as a promising rugby player.

The dispute began on Thursday and by the early hours of Friday, Thomas Jones a local Councillor, Magistrate and grocer, requested assistance from the army to maintain order in the town. The Home Secretary Winston Churchill agreed. Anxiety after all was rife. The and the most important duty it had was to maintain order in the face of industrial unrest and anything which might threaten social order.

The Lancashire Fusiliers were sent down from Cardiff. They had been stationed there after policing the Miner’s Strike in Tonypandy. They were skilled and experienced and relations between the strikers and the troops on Friday were fine.

However, Thomas Jones did not want the strike sensitively policed. He wanted the strike broken – perhaps because, as a shareholder in the Great Western Railway, he was concerned about his dividends. More troops were ordered in, this time the Worcestershire Regiment under the command of Major Brownlow-Stuart. By now there were 370 soldiers in the town, which was hardly likely to improve the mood of the dispute.

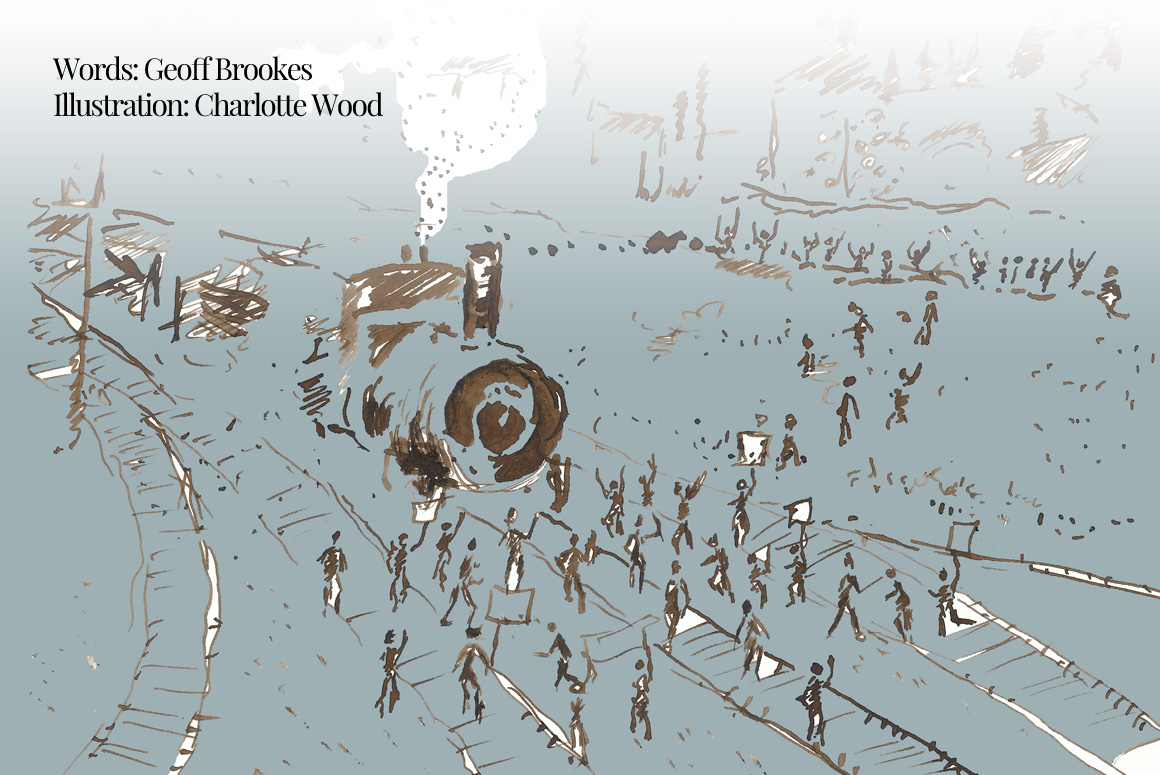

On Saturday 19 August there was a mass picket at Llanelli Railway Station. This was a powerful gesture by the strikers, showing they could block the Great Western Railway. Sadly what the railway workers saw as a negotiating strength became a fatal weakness, since this disruption to supply routes to Ireland and the troubles there could not be tolerated.

A train allegedly carrying strike-breaking workers tried to pass along the line through the town, enough to inflame further highly-charged emotions. The train had been held up and the Commanding Officer of the Worcesters ordered the troops to use bayonets to part the crowd. This allowed it to creep through carefully, but strikers forced themselves on board and raked out the engine fire, thus immobilising the train. The troops who had followed it were trapped in a cutting where the strikers threw stones at them. Major Brownlow-Stuart asked the JP to read the Riot Act, which he did, but so quietly and nervously that it is unlikely that anyone heard him. It was the last time it was read in mainland Britain and had fatal consequences. The Major then ordered his men to fire their rifles. Shouts went out from the crowd that they should not worry, the shots would be blanks. But they were not, the rifles were loaded with live ammunition. Two men were shot, one entirely unconnected with the disturbance – John “Jac” John and Leonard Worsell. In that moment they became working class martyrs.

Leonard was not a Llanelli man at all. He was 19 and came from Penge in south London and was visiting the Allt y Mynydd sanatorium near Llanybydder where he was convalescing after contracting TB. He had been shaving and had come into the garden of 6 High Street to see what all the fuss was about, after the strikers, including Jac John, had spilled into the garden. He stood there, bare-chested and bare-foot watching the show.

Leonard was not a Llanelli man at all. He was 19 and came from Penge in south London and was visiting the Allt y Mynydd sanatorium near Llanybydder where he was convalescing after contracting TB. He had been shaving and had come into the garden of 6 High Street to see what all the fuss was about, after the strikers, including Jac John, had spilled into the garden. He stood there, bare-chested and bare-foot watching the show.

Major Brownlow-Stuart said they were merely warning shots that unfortunately went astray. Leonard had bared his chest as an act of defiance which naturally required a response. Some witnesses however later claimed the two men were deliberately targeted. What is beyond dispute is that Leonard was shot through the heart. Jac received a serious and fatal chest wound. Others were wounded.

There was an inevitable explosion of rage. The Worcesters were forced to withdraw to the station and they barricaded themselves inside to protect themselves from the howling mob outside. Llanelli was poised on the very edge of an insurrection.

Shops were attacked and looted, starting inevitably with Thomas Jones’ shop and two of his farms.

One man used dynamite to open an armoured freight truck, looking for whatever he could get. Sadly the truck contained munitions and he was killed, along with three others, in a huge explosion. A soldier, Harold Spiers, refused to fire on the crowd. He was arrested but escaped and went on the run. There was a real fear that there might be a mutiny.

The streets were eventually cleared by another 300 soldiers from the Sussex Regiment who were rushed to the town. There were now almost 700 troops in Llanelli, this ordinary Welsh town had an army of occupation. In these circumstances people with bayonet and baton wounds refused to seek treatment for fear of arrest. When Monday came the children at Bigyn School in the town went on strike in sympathy.

The great irony was that whilst the crisis was unfolding a national settlement of the dispute was reached, brokered by Lloyd George at the Board of Trade. The strike was at an end.

The madness ended too and sense of shame descended on the town. The local paper said “Llanelli from now on will not be known as a peaceful town but as the abode of rioters, thieves and drunkards.” So it did its best to try and wipe it away. Saturday 19 August 1911, a day to forget. The day that never happened.

As the years have gone on there has been greater willingness to engage with these shocking events.

There is now a blue commemorative plaque at Union Bridge on Queen Victoria Road, which marks the cutting where the train was stopped. The centenary was marked by rallies. There were speeches and of course there are the graves which have been refurbished as part of a town’s duty to its past. They can’t be forgotten now as they are well-cared for and often visited too, as everyone knows how to find them. They are about 50 yards apart and the path between them is well worn. They will never slip into a comfortable obscurity.

Leonard’s family could not afford a funeral so the War Office kindly donated £4. Major Brownlow-Stuart was promoted and retired as a Brigadier-General in 1919. He died in 1952. The court returned verdicts of “justifiable homicide.” Everything became ordered once more. But for a long time the Worcestershire cricket team was known locally as “The Murderers.”

Feat image: Funeral of two men killed at Llanelli during the 1911 Railway Strike (Source)