![]()

The grave seems overlooked now, an event once important enough to be mentioned in Parliament, but now long forgotten. The stone is one of many that line the pay & display car park at the end of King Street in Aberystwyth. It was moved and placed here some time ago. It is next to the church of St Michael, which lies on the edge of town, up against the sea. The castle grounds, neat and picturesque, protect the church from the sea, though the church was not always able to protect its congregation: many gravestones refer to death at sea – sailors lost overboard, for example.

You will find such graves in all of our seaports, men who went out to sea and never returned to their families. The last time we were there, generations of families were stretched out on the grass, enjoying the sun. They still had to shelter from the traditional wind off the sea, which always seems to throw itself at Aberystwyth. Children played on the grass, surrounded by the re-sited gravestones whose histories and stories are now less important than their role as a border.

You will find an archway in the south corner where there is a lovely inscription which begins with the arresting words,

Stop Traveller, stop and read. This stone was erected by those who fully appreciated the integrity and fidelity of David Lewis, alias The Old Commander.

David Lewis died in 1850 at the age of 66. He fought on the ‘Conqueror’ under Nelson at Trafalgar and for 13 years he was a respected deputy harbourmaster. He was able to build a longer life of achievement than James Williams, the young man whose grave we had come to find.

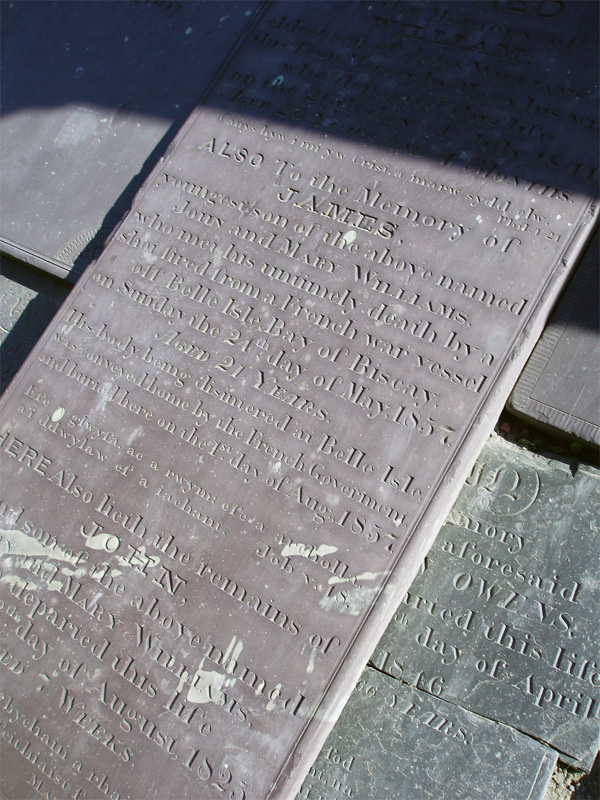

Down by the arch you will find the Williams boys, three of them. Their father, James, was a mercer and he and Mary buried their three sons, John, William and James. How difficult that must have been. Squeeze past the bumpers of the cars and you will find them all. The stone has slipped down to cover those beneath it but it remains, thankfully, undamaged.

The parental grief that it describes is hard to imagine. William died in July 1841 and John, their second son, died in 1825, only 7 weeks old. But it was James who had drawn me to this car park. When he died at the age of 21 he was serving in the Merchant Navy on the schooner John and Edward. It had left Bordeaux bound for Liverpool on 24th May 1857. A contrary wind forced them to shelter in Quiberon Bay in Brittany in the harbour of Sarzeau on the north-east coast of Belle Isle. Since they had been driven in by the weather, the necessary signals were not ready to be hoisted. They anchored close to the stern of a French man-of-war, the Maratch.

The French hailed the John and Edward, but the captain, James Evans, could not make himself understood.

The French hailed the John and Edward, but the captain, James Evans, could not make himself understood. All he could do was shout loudly, “Liverpool!” This was not good enough and the French fired a shot – a blank as it turned out – to persuade the British ship to fly its flag. They were keen to know who they were.

The captain’s wife immediately produced a flag and a member of the crew waved it frantically.

A second blank shot was fired. This perhaps reflected impatience, rather than a sense of threat. James Williams was scrambling in the rigging when there was a third and this time live shot. It hit James as he worked to haul up the ensign. He fell to the deck. Mrs Evans said in a letter, “He did not sigh or groan.”

They launched a boat and went to the Maratch to tell them. They sent their doctor, but it was too late. James was dead and was buried in Belle Isle.

Mr Lewis Dillwyn, MP for Swansea, outlined these unnecessary events, in Parliament, and his comments were duly recorded in Hansard. It was the Prime Minister, Viscount Palmerston, who replied to the issues he raised. He confirmed that the first two shots were blank musket rounds. He acknowledged that the John and Edward was at fault, for “no ship ought to enter the harbour of a foreign country without colours to distinguish her nationality” but there was certainly no justification for ordering a live round to be fired at the ship. The French officer said he ordered the shot to be fired high, but “the ball glanced and unfortunately the shot took effect.”

Even before the British Government could complain, the French had called in the British Ambassador in Paris, and Count Walewski offered a full apology of “the most satisfactory and handsome kind”, according to Palmerston. Orders had already been given to “dismiss from the French service the officer who had given orders to fire the fatal musket shot”, which provoked cries of “hear, hear,” in the House. Palmerston’s reassurances that the French Government wanted to “mitigate the affliction of the family of the unfortunate seaman” led to cheers.

How easily the House was moved to emotion, even in those days. In fact, Palmerston was impressed by the way the whole incident had been handled, certainly in ways which would not impact adversely upon the Williams family back in Aberystwyth. “Nothing can be more honourable and proper than the manner of their proceeding towards the English Government on the subject,” he said. How very noble and supportive, but cold comfort to a family that had now lost its third son.

The Williams family were assisted by their MP, Captain Pryce, and through his attentions Sir Anthony Perrier, Her Majesty’s Consul in Brest, arranged for James to be sent home. He arrived in Aberystwyth, in state, on 1st August 1857 on a French ship and was reburied in his home town.

The perfidious French. The press made much of the patriotic details – a young boy in the rigging, tangled up in the Union Jack and killed by a musket shot that had gone through both James and the flag. However you want to present it, the fact remained that he was dead, but a major diplomatic incident was avoided through carefully choreographed compassion. The right things were said, and the world moved on.

James Williams was an ordinary boy from Aberystwyth who became an unexpected issue for the Prime Minister, and a family tragedy was carefully managed by the Civil Service – so well, in fact, that his gravestone is now a forgotten part of the boundary of a pay & display car park above the sea in Aberystwyth.

So what of his ship, the John and Edward? That, too, was lost, in a severe storm off Holyhead in October 1858.