![]()

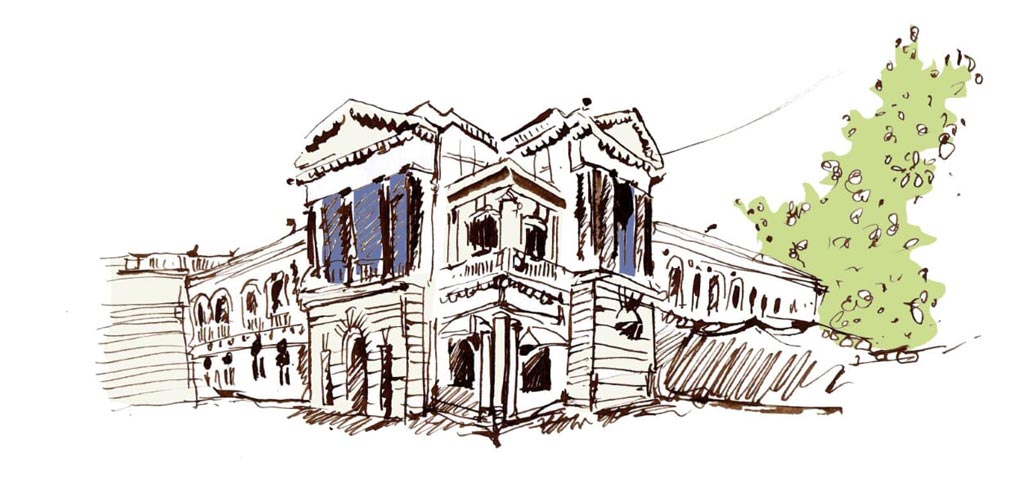

In the graveyard of the fine parish church of St Giles in Wrexham you will find the substantial tomb of Elihu Yale, who was buried here in 1721 and has a world-famous American university named after him. It is large and unmistakeable, sitting close to the porch on the right hand side. It has on it an interesting biographical epitaph, allegedly written by Yale himself.

Born in America, in Europe bred

In Africa travell’d and in Asia wed

Where long he liv’d and thriv’d; In London dead.

Much good, some ill, he did; so hope all’s even

And that his soul thro’ mercy’s gone to Heaven.

You that survive and read this tale, take care

For this most certain exit to prepare

Where, blest in peace, the actions of the just

Smell sweet and blossom in the silent dust.

His is a strange and unexpected story, one that challenges our modern sensibilities and still causes real discomfort. Elihu Yale was certainly a man of his times, but as a sometimes brutal slave trader, his legacy is unsettling.

His family had been part of the Puritan migration to Massachusetts and had settled in Boston. Elihu Yale was born there in 1649 but, even though his grandmother had married the governor of Newhaven, the family returned to London in 1672, finding the regime of the colony rather grim.

Yale never returned to America and spent much of his adult life working in India for the British East India Company, rising steadily to a senior position, which enabled him to amass a considerable personal fortune through a range of corrupt practices. He became the governor of St George Fort in Madras (now Chennai) marrying his predecessor’s widow, Catherine. He also kept two mistresses, one of whom, Catherine Nicks, was a notorious diamond smuggler.

It is impossible to establish just how much money he accumulated in India, through numerous illicit activities including diamond smuggling. Yale also earned a great deal from his involvement in the slave trade.

He sold a large number of slaves to the settlement of St Helena and introduced a regulation that every European ship leaving Madras must carry with it a minimum of ten slaves to be sold, which he provided. In 1687, in just one month, 665 people were trafficked out of India. When demand for slaves increased, the traders began kidnapping young children. Yale himself was notoriously brutal. Slaves were whipped and branded. He “hanged his groom for riding out with his horse for two or three days to take the air without his leave.”

His lasting legacy in Madras was the building of a hospital in 1664 to care for the health of English families, soldiers and merchants but his greatest motivation was always profit.

Yale was eventually removed from office in 1692, his habit of buying land for his own purposes using East India Company money proving to be a step too far. Catherine had left him earlier, in 1688 and Yale removed her name from his will, substituting the words, ‘my wicked wife.’

He was detained in India until he was eventually allowed to leave in 1699. Back in England he lived quietly, dividing his time between London and the family property in Plas Grono near Wrexham which had been acquired by his great grandfather David Yale and is now part of the Erddig estate, a National Trust property. Plas Grono was demolished in 1876.

Despite his fall from grace in Madras, he was still ridiculously wealthy. It is believed that he acted as the first auctioneer in England when he sold off some of his property, since he had brought home so many possessions he did not enough room for them in his house. After his death, seven separate auctions were required to dispose of his property. It included several hundred snuff boxes, 500 rings, 100 canes, 7,000 paintings and 116 pairs of cufflinks.

As he grew older, Yale devoted his time to the church and served as the high sheriff of Denbigh. Perhaps his Christian beliefs encouraged a time of reflection and regret, who can say? He was certainly a benefactor of St Giles’ Church, donating devotional paintings. He paid for a new gallery across the east end of the nave which “contained several pews, of which the six front ones were to be at the disposal of Mr Yale and the remainder at the disposal of the Churchwardens.” In 1718, he became dissatisfied with the position of this gallery and so removed it and reinstalled it at the west end of the nave. It is on occasions like this that you may be reminded of the old Welsh proverb – “The closer to the church, the further from God.”

It was in that same year that Yale created his place in history. He had previously presented a set of thirty two valuable books to the Collegiate College at Saybrook in Connecticut but when it relocated to Newhaven, he received a letter from Cotton Mather, the religious writer in Connecticut.

Mather had written Magnalia Christi Americana about God’s chosen people – the puritans – and their heroic story, “fleeing from the deprivations of Europe to the American strands” where they “irradiated an Indian wilderness.” He was not too proud however to accept European money and asked Yale to help the school, now that it had moved. Yale responded by sending a gift of nine bales of goods, together with 417 books and a portrait of King George I. The sale of the goods raised money for a new building, creating the basis on which the university was founded, the third oldest institute of higher education in America. It later changed its name in recognition of this gift in 1745 to Yale University. It may be interesting to note that, just before his death, he sent out a further miscellany of goods for them, though they were, allegedly, lost in transit.

Yale was 73 when he died in London in July 1721 and was buried in St Giles’ in Wrexham, where that solid tomb still squats.

For a while there was a desire to promote the links between the University and Wrexham. It was certainly something about which the town was proud and the university liked the idea of its Old World origins. There were frequent exchanges and visits, enthusiastically reported in the press.

On a visit in 1874 members of the University found that those words of the epitaph had eroded so badly that they arranged for the letters to be recut. In 1900 American visitors expressed some dissatisfaction with the tomb and decided to send over a new memorial “of elaborate design showing Yale lying at rest under an open canopy worked in stone and marble.’ The plan, perhaps thankfully, came to nothing, as did the scheme to take the tomb and his remains back to America. In 1902, on the bicentenary of the founding of the college in Saybrook, Yale University raised £400 to restore the north porch of the church and representatives laid wreaths on his tomb. In 1918 a stone from the west tower was taken to America and inserted in the walls of a new university building as a physical representation of the links between them.

But the interest faded as times changed. His legacy began to conflict with the modern world and eventually those links proved to be an embarrassment. As an enthusiastic slave trader and fraudster, Elihu Yale was no longer the sort of person with whom a university might like to celebrate a relationship, since he hardly complies with Yale’s values. After all, he is regarded in India as an “arrogant ruthless braggart…who cheated both his employers and the people of India.” After complaints from students in 2007, a portrait of Yale with a dark-skinned servant wearing a metal collar was removed from a wall in the university.

Yale University has already changed the name of one of its constituent colleges that had been named after an advocate of slavery. They might well move on to the renaming of the university as a whole.

But that epitaph on his tomb that he allegedly wrote himself? Well, the last two lines are lifted from a seventeenth century poem by James Shirley, Death the Leveller. If you look at it closely you will notice the regret and anxiety of lines 4 and 5. “Much good, some ill, he did; so hope all’s even /And that his soul thro mercy’s gone to Heaven.” Those words are, I think, particularly revealing.