![]()

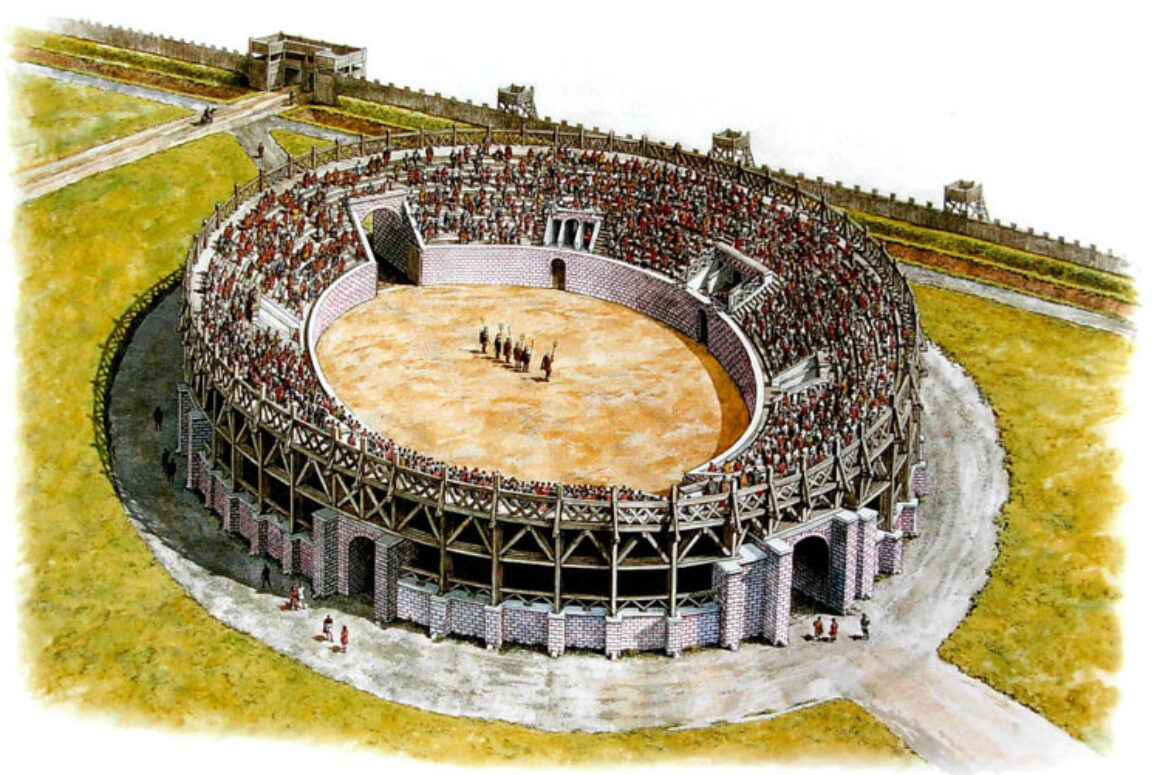

The year of 700 A.D. heralded the end of Roman Caerleon, which was destroyed by the Saxons in a sudden attack. Yes, the attack was definitely sudden and it could have been at night because excavations there in 2010 discovered Roman steel armour for fighting purposes and yet more Roman bronze armour for ceremonial use, complete with chainmail and weapons, lying intact in the ruins of the armoury there, which clearly proves that Caerleon’s legion was caught by surprise.* The same series of excavations also discovered accidentally – when some students were practising with geodesic surveying instruments in a nearby field during pauses in the excavations of the fortress under the present town – the largest building complex in Roman Britain, namely, a huge palace and two or even three much smaller and superficially identical buildings, which I conclude must have housed the archives and administrative staff of Caerleon’s succeeding kings and former governors. Everything had been burnt and therefore all the records of Caerleon’s administration and history were destroyed ‘at a stroke’. The Saxons continued with their genocidal policy of killing the ‘waesla’ (which meant ‘foreigners’ in the Saxon language: what a blinking cheek!) by murdering as many of Caerleon’s inhabitants as they could catch, followed by burning the city down to the ground and demolishing as much of it as possible but they gave up trying to destroy the massive stone amphitheatre as a bad job: it is still the most complete example in Britain. The population of Roman Britain is estimated to have been around 3,500,000 in 410 A.D. when Britain declared independence from the Roman Empire but the invading Saxons had reduced it to roughly 500,000 by 700 A.D.

The last King of Caerleon was Morgan ap Athrwys¹² (also called Morgan Mwynfawr, which means Morgan the Benefactor in English). He was the son of the preceding King Athrwys ap Meurig¹³, who had died in about 665 A.D. King Athrwys ap Meurig was a brilliant military leader who kept the Saxons at bay by winning several important battles against them. Morgan ap Athrwys fled westwards to a safe area with the remnants of his army and the surviving citizens of Caerleon, where he founded Glamorgan (named after him) in the same year of 700 A.D. I assume that he chose the Roman city of Cae r Dydd (Cardiff) as his military capital and Llanilltyd Fawr (Llantwit Major) as his cultural capital, which was a sizeable town with a huge and internationally renowned “monastic college that incorporated 7 halls” according to a Welsh text. It had been founded by Saint Illtyd¹⁴ himself in about 520 A.D. on the orders of Saint Dubricius to replace the ruined and equally famous Cor Tadwys (College of Theodosius I) on the same site, which had been founded in about 385 A.D. (probably by Theodosius himself) and was destroyed by Irish raiders in 446 A.D.

The ruins of Roman Caerleon, which I estimate comprised about 20,000 buildings, were still clearly visible to the Welsh historian called Gerallt Gymro (Gerald of Wales in English) when he visited the ‘new’ town of Caerleon in 1188, i.e., almost five whole centuries after it had been destroyed. In fact, some of the city’s remains even survived for six more centuries: William Coxe mentions them in his famous ‘An Historical Tour Through Monmouthshire’ that was published in 1801, which actually summarizes three tours that Coxe had made there during the 1790s.

* On the other hand, Caerleon’s legion could have been routed by a vastly superior Saxon force in a pitched battle, as had happened to Chester’s legion (with supplementary Welsh troops) in 616 A.D. In that case, Morgan ab Athrwys and his defeated army would have beaten a hasty retreat to Caerleon and evacuated as many of its citizens as possible before the Saxon onslaught: they would simply not have had the time to remove their spare armour and weapons from the fortress.

I estimate that the population of Roman Caerleon was at least 120,000 (about the same as London at its zenith around 400 A.D.), which must have swelled by 50,000 or even more as refugees poured into it from what is now Herefordshire between roughly 570 A.D. until about 600 A.D. when the Saxons finally took over that Welsh territory. Even so, there are still several place-names in Herefordshire that begin with ‘Llan ….’, which is the Welsh word for “church and its parish” and the Romano-British culture lingers in Herefordshire nowadays in the form of cider, as it is does in Somerset and Brittany too. Cider is a Romano-British beverage

The Romano-British, or rather Brythons as they called themselves, (the word Welsh is derived from the Saxon word “waesla” – see above – which the Normans modified to “Walsh”) had been defeated but they were just as indomitable as ever and they were determined to recover their lost ground after making careful preparations. They had developed the most lethal of all mediaeval weapons during their exile in Glamorgan, namely the Welsh Longbow, which was 2 yards high and fired an arrow 1 yard long that could penetrate 1/2 inch of tempered steel (armour plate and chainmail) or several inches of hardwood (refer to Gerallt Gymro’s description in his Itinerarium Cambriae of Welsh arrows that penetrated and were embedded in Abergavenny Castle’s drawbridge) at a distance of 300 yards. It was this irresistible weapon that enabled them to recover Caerleon from the Saxons in about 730 A.D. (and also ensured that Llewellyn the Great’s army killed 3,000 soldiers of King John’s army in one day several centuries later and literally pinned down another of his armies for 2 days, thereby regaining independence).

However, the Welsh force that returned to Caerleon from Glamorgan merely repaired the breached walls of the ruined fortress and built a little town of Caerleon inside it; they utilized the ruins of the destroyed capital as a convenient quarry. In other words, they never attempted to rebuild Caerleon – which admittedly would have been a colossal task employing thousands of men for many years – but they did recover the county of Gwent, which the English later called Monmouthshire and it has always remained on the Welsh side of the border ever since, even though Shakespeare mentioned “Wales and Monmouthshire” in one of his plays, perhaps with the meaning that Monmouthshire was the most important part of Wales in his time, instead of it being an English county.

To summarize, the value of Chrétien de Troyes’ Legend of King Arthur lies in its perpetuation of the facts, albeit in a distorted form. In a similar way, it is thanks to Homer’s Legend of King Minos that Sir Arthur Evans travelled to Crete in 1900, stuck his “spade into a hillside covered with pretty flowers” and ….. discovered the Palace of Knossos along with the ‘mythical’ Minoan civilization.

Unfortunately, the ‘conventional wisdom’ that prevails in historical and archaeological circles nowadays falsely asserts that:

1) Caerleon has always been an insignificant village.

2) Caerleon was never a major Roman city – let alone a CAPITAL city and the ONLY major Roman city to have survived after York, London and Chester had all been destroyed by the Saxons (Chester lastly in 616 A.D., following the Battle of Chester when a combined Welsh army from Powys and Gwynedd was defeated by the overwhelming forces of the Saxon King Aethelfrith of Northumbria; a few days prior to which he had ordered 200 Welsh monks to be massacred because he feared that they were praying against him, despite being a heathen himself; he died shortly after the battle, which was interpreted by the surviving Romano-British as divine retribution).

3) Caerleon did not have a cathedral or a church during the Roman era.

4) King Arthur is the figment of a Frenchman’s imagination, as are the Isle of Avalon, Guinevere, etc.

BUNKUM!

References

12. Book of Llandaff: Morgan ap Athrwys (630 – 730 A.D.) was succeeded by Idwal ap Morgan, who reconquered Gwent.

13. Annales Cambriae

14 .Vita Sancti Sampsonis and Vitae Santorum Britanniae et Geniologiae

* Probable locations to search for this book: the Rhuys Peninsula in Cornualia, Brittany, especially around the ruins of Saint Gildas’ monastery there, which the Normans destroyed in the 10th century (the present abbey was built over it and consecrated in 1032); the town of Troyes, south-east of Paris; the town of Monmouth in the Welsh county of Gwent.

© John H. Griffith-Davies, 2020.

Feature image: Reconstruction of the Caerleon amphitheatre from the end of the 1st century. Source.