![]()

King Arthur has been a long time study of historian John Griffiths Davies who here gives an introduction to his detailed paper which we will publish over the next 4 weeks.

My study deals with some of the important events that occurred during the late epoch of Roman Britain in Cambria (Wales) and Britannia Prima (western and south-western England), which was brought to a violent and abrupt end in south-eastern Wales by the Saxons. I have discovered that they destroyed Caerleon in 700 A.D., which was the capital of Britannia Prima, as well as the last and largest of the major cities in Roman Britain. By the way, I have also discovered that Caerleon was the main centre of pilgrimage in Roman Britain from circa 325 A.D. to exactly 700 A.D., in order to visit the shrines of Saint Aaron and Saint Julius who had been martyred in the amphitheatre there in 304 A.D.

My study is an original work about the so-called King Arthur, whom I have incontrovertibly identified as Brenin (King) Athrwys ap Gwythr. He was a Romano-Briton living from circa 480 A.D. to exactly 537 A.D. in Caerleon. I have also solved the mysteries of ‘Camelot’, ‘The Isle of Avalon’, Guinevere, inter alia, while doing so. My ground-breaking study results from 3 years of intensive research and I wish to point out that it invalidates the commonly held view among historians about all of the aforementioned subjects by default.

Prof. Gareth Davies in the Faculty of History at the University of Oxford , who is one of many historians, archaeologists and classicists that have responded to my study favourably, commented on it as “How fascinating! Well done.” Prof. Davies has suggested that I should arrange for my study to be published in a magazine so as “to reach a wider audience“.

Mr. Gary Manners, Editor of Ancient Origins, commented on my study several weeks ago, as follows: “I think it is really excellent material. … You have found some good primary sources … while keeping the story alive. SO well done. I found the information very interesting.”

Prof. Roland Hutton, Department of History, University of Bristol, has complimented my study as “clearly relevant” and “very valuable“.

Prof. John Osborne, Department of History, Carleton University, has responded to my study as “very interesting“.

Mr. Jonathan Adams, President of the Caerleon Civic Society, has confirmed that my study “makes fascinating reading“.

Prof. Richard Wenghofer, Professor and Chair of Classics at the University of Nippisingu, Ontario, has described my study as “all very interesting” and “profoundly stimulating”.

Professor Helmut Reimitz , Professor of History at Brown University, Providence, Rhode Island, has commended my study as “fascinating material“.

Prof. Stephen Mexal, Chair of English, Comparative Literature and Linguistics at California State University, Fullerton, remarked: “Congratulations on your project.”

Dr. Gareth Davis (not Prof. Gareth Davies of Oxford!), History Tutor, Swansea University commented: “I congratulate you on your work.”

I would also welcome comments on my study too. In a nutshell, the matter concerns not only rehabilitating Brenin Athrwys alias King Arthur as an outstanding patriot of the Brythons (Romano-British) but also Caerleon as the last surviving and most important capital of Roman Britain.

The editor of Historic UK magazine, who signs herself as “Deborah J.”, has commended my study as “absolutely fascinating” and she offered to publish it too but only if I ceded the copyright to her magazine without further ado! I refused to do that of course because the legal (Roman) principle of quid pro quo applies, i.e., so-called author’s rights.

Regarding the archaeological aspect, I consider it highly likely that architectural and artistic remains, e.g., an intricately carved cornice that Coxe described in his guide entitled ‘An Historical Tour through Monmouthshire’ (published in 1801 and resulting from 3 exploratory trips that he made there during the 1790s) after visiting Caerleon, are waiting to be (re)discovered on this green field site around the present small town of Caerleon (which was refounded in about 730 A.D. within the breached walls of the ruined Roman fortress: the soldiers’ former billets were improvised as pig-sties!), not to mention some sculptures of saints, Roman deities and the like, as well as mosaics and artefacts such as pottery and coins.

Excavation of the Druid centre on the largest island in the Afon Lwyd tributory (i.e., the ‘Isle of Avalon’) of the River Usk near Caerleon would undoubtedly reveal the tomb of Brenin Athrwys (but not that of his second queen Gwenhwyfar, i.e., Guinevere, who I deduce was buried in the cemetery of the convent attached to Saint Julius’ Church because she ‘took the veil’ i.e., became a nun (which was even more of a one-way trip at that time than it is nowadays!) and the subsequent kings of the dynasty that he founded too.

Concerning the Christian aspect, excavating and restoring Roman Caerleon’s important religious buildings such as Saint Aaron’s Cathedral (perhaps including his shrine inside it and that of Saint Julius in his own mother church if there are enough remains left of them after the Saxon destruction by burning followed by demolition) would greatly benefit one’s appreciation of Roman colonial architecture and art. Please refer to Footnote 7 of my study concerning this matter.

In fact, I consider that the – as yet ‘undiscovered’- ruins of Roman Caerleon are the British equivalent of Pompeii and further excavations will definitely be required: the most recent excavations were halted abruptly in 2013 (I wonder why?) after students practising with geodesic surveying instruments in 2010 during breaks from excavating the fortress accidentally discovered the largest complex of buildings in Roman Britain: the excavation’s sole purpose until then had been to investigate the fortress. I have identified the main building in this complex as the governor’s residence (which became Brenin Athrwys’ palace, i.e., ‘King Arthur’s castle’) and the other 2 similar but smaller buildings (possibly supplemented by a third one that was subsequently built between them and the main building) as the archives and administrative centre.

© John H. Griffith-Davies, 2020.

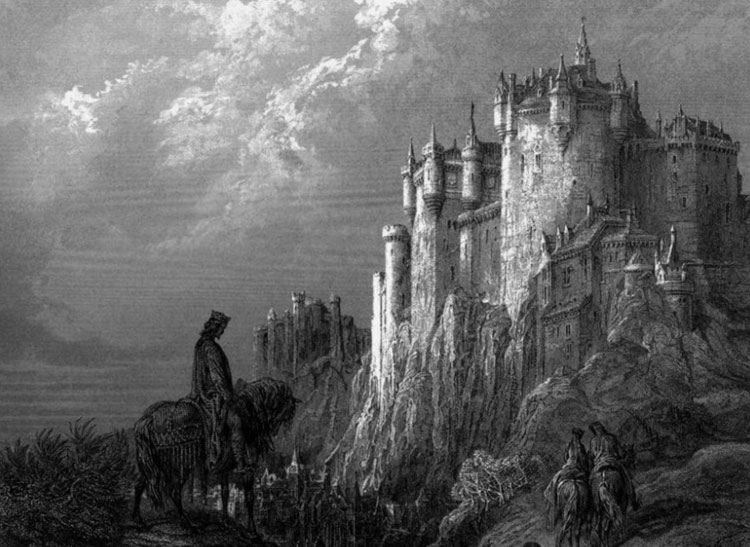

All images used are generic and relate to the many fictional tales of King Arthur.