![]()

At first, I didn’t like it. The Lower School was a tall, forbidding stone building on Meyrick St. in Pembroke Dock. The playground, too, had high prisonlike walls surrounding us and a covered area where we could huddle together in bad weather. The boys and girls appeared to be segregated in the playground though I can’t remember a physical demarcation. When play was over we lined up and a master would oversee us as we entered the buildings, boys and girls separately. I missed Angle Primary School where there was only a low wall separating you from the village street. You could sit on it and chat to local characters and even, on occasion, see your mother or father going into the village shop or post office. ‘The Corra,’ by comparison, was more of a fortification.

Inside, however, it was less gloomy. There was a large hall off which classrooms were reached by stairs, mine, I seem to remember, overlooking the street. There, our form-teacher, Mrs. Shaw, an elegant nice looking woman smiled at us. She also taught us English — and possibly history — and ran the library, I becoming one of her helpers which earned me an enamel badge proclaiming that position. Other lessons I remember were the ones given by the PE teacher, Mr. Allen, who advised us how to find where north was by reference to the bent SW facing Pembrokeshire trees. I suppose the subject was something like Outdoor Pursuits but as far as I can remember we never put theory into practice. Similarly, Bird Watchers’ Club, which met on a Friday afternoon in the nearby Bethel Chapel, run by Mr. Owen who was genial enough, never ventured out into the field. We painted pictures of birds which were then miraculously thrown up on a screen by some sort of projector. This took my fancy, so much so that I was elevated to chairman of the club but in the event I never chaired anything, a blessing as I was very retiring. I remember nothing of maths lessons — I struggled– though I do remember the handsome headmaster, Mr. E Lloyd-Williams, descending on us once from the Upper School in Argyle St. and conducting a mental arithmetic exercise where you were elevated — we stood in a line in front of him — if you answered correctly. Innumerate, I sank to the bottom.

The headmaster of the Lower School, however, was hardly a glamorous figure: Mr. Edgar Thomas was a short bald man with firm views on correct behaviour and morality, rather in the manner of an Old Testament prophet. It was under his eye that we chanted weekly, or was it daily?, the Code of Honour. Standing in straight lines, we wheeled to our left and read from a plaque, and bellowed:

‘Do the right because it is right!’

‘Help the weak and those that are down!’

‘Abhor mean actions!’

Benign Orwellian chanting! The last command conveyed little to me as I didn’t know what ‘abhor’ meant. There were other strictures but I can’t remember them. Sometimes we listened to, and sang with, hymns which crackled out from an ancient loudspeaker:

‘Hills of the North rejoice

Valley and Lowland Sing!’

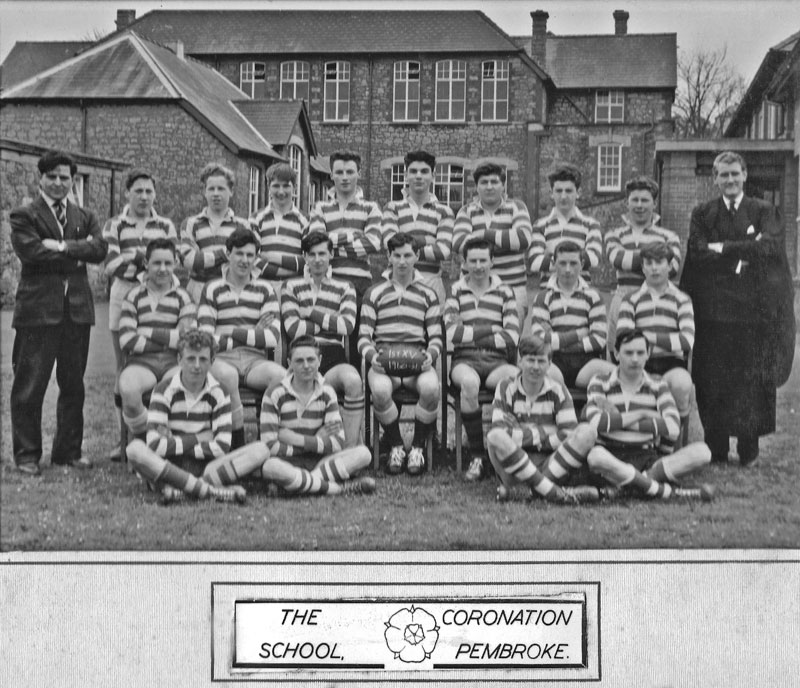

I had friends, of course, one in particular, Richard Thomas, who lived in Clarence St. There, at lunchtimes, I went along Bush St. for some way and turned right and played happily with a rather splendid train set. Another outlet was athletics. Although asthmatic I could run quickly over a short distance. ‘The Corra’s’ white and red stripe outfit, handed out in tissue paper from boxes when you represented the school at the County Sports, was the smartest strip there and treasured by you, even if it was only on loan.

In the third year we transferred to the Upper School in Argyle St, a building recently vacated by the grammar school who had a brand new site at Bush. Low railings which you could see through — and over if you were tall enough — surrounded a lowish building which had some grassy areas surrounding it. Furthermore, there was a park opposite in which we could roam at lunchtimes. The rather nice Mrs. Shaw followed us there and taught us history. I liked the humanities and was quite good at them but not the technological subjects which boys were supposed to follow. I rebelled and did Human Biology with Nursing and Arithmetic with Commerce, both subjects heavily dominated by girls. The former was taught by Mr. Griffiths, the latter by Mr. Sabido who later in life distinguished himself as a rugby official in the WRU. Human Biology was taught in a prep room, a small, friendly atmosphere pervading. Not so Physics which I did for a mercifully short time. Mr. Brown, scrupulous, of a stern, military bearing, explained — but not to the baffled me — fulcrums and pulleys. On one occasion a boy stepped out of line whereupon swift efficient corporal punishment was dispensed, the boy, understandably, returning from the prep room with tears in his eyes. But he didn’t catch Bernie Stone who, on one memorable occasion, warbled through an air vent from outside, the sound echoing around the classroom. We knew it was Bernie as he had a distinctive Cosheston chuckle. How Bernie wasn’t caught was something of a mystery as he wasn’t built for speed.

I began to get fitter and less asthmatic and eventually got in the rugby team by something of an accident, the team desperate on a Friday night as a prop had dropped out. Mr. Dai Williams intervened, spotted me as I was about to get on the Angle bus and said something like ‘he’ll have to do.’ My one game at prop! I was then isolated on the wing where I could do less harm. The late Hugh Jones was captain. He was an enthusiastic tackler and once felled a big lad, Raymond Lewis I think, who was stretchered off unconscious, Hugh distressed by the outcome of a legitimate enough tackle.

I suppose it could be argued that dancing was good training for rugby. It was taught by Mr. Dannie Hordley and the senior mistress whose name, I think, was Miss Hobson. Before battle commenced boys and girls lined up separately on either side of the school hall and when the order was given the boys shot across the hall and asked a girl to be a partner. I always asked a girl I knew well from Angle school, never an exotic creature whom I might have fancied. Then Miss Hobson demonstrated some steps — I think it must have been country dance orientated — which we attempted to emulate. The music was played by Mr. Hordley, possibly on the piano though something tells me it might have been a squeezebox. This, together with the practice provided by Angle Village Hall dances, has made me a tolerable practitioner of, say, The Gay Gordons.

I enjoyed Art with the charming Mr. Carradice — and later with Mr. Wyndale — who once a week or so addressed the whole school about a painting. We stood in serried ranks, listening, trying to see the picture from the floor of the hall. Once, the boy behind me, asked to be taken out as he said he felt faint. He bounced off me and others as we assumed he was fooling about. When he crashed to the floor we realised he wasn’t joking.

Mr. Finch — aka ‘Tweet’ naturally enough — was the deputy head and attempted to keep us quiet as we filed in and took our places. Once he shouted: ‘You, the boy with the red tie, get out!’ We were confused as we all wore red ties. Similarly, in his youth, he bamboozled the New Zealand fullback, Nepia, when he scored a try for Llanelli in 1924.

I tended to avoid performances largely because of shyness, apart from being in the school choir. This was thoroughly rehearsed for the annual carol service in Bethel Chapel, Mr. Dannie Hordley the major domo. He controlled us with a thin white baton with a cork handle which snapped when he got exasperated. But things such as drama and eisteddfodau, I avoided. However, ambitious productions were put on under the expert guidance of Mr. Aubrey Phillips. I remember a friend, Roy Campodonic in, I think, The Merchant of Venice. And very good he was too. A greater number of people participated in the Eisteddfodau. There was keen competition between the four houses, named I now realise after the Anglo-Norman war-lords Clare, Marshall, Valence — and one I forget! I was in Clare, our house colours blue. I can’t say I enjoyed four house choirs singing the same song, but worse was the artificial chanting of choral speaking. But I was interested in submitting a painting — though I couldn’t compete with the very talented Keiths (Palmer and Beynon) but I was delighted one year when I won the metalwork entry. Mr. Harry Jones, a keen fisherman, based in the Lower school, taught this whilst Mr. Norman Nash — ‘You stand like a boxer, boy, when you plane wood’ — taught woodwork, he based in the Upper School. I suppose I couldn’t have had the necessary pugilistic stance as I was turned down for the woodwork class.

My best friend in the Upper School, Kenny Crockford, came from Tenby and was considered by many to be the best clown in the school: his humour was facial, he specialising in boggle eyed expressions based on, I think, Mike and Bernie Winters, a comic pair of brothers of the 1950s. Like me, he avoided technology and did subjects such as typing, usually the domain of the girls. Some of these were far flung, one in particular from over the water in Neyland. Because of her beauty I formed the opinion that Neyland must have been an exotic place. She took the ferry every day to Hobb’s Point. The fact that these two came from outside the catchment area demonstrated the fact that ‘The Corra’ wasn’t a ‘bog-standard’ sec. mod. Indeed, there was even a Certificate Class which studied for ‘O’ Levels. And in 1961 I managed to cobble together, with the help of supportive teachers and a patient father, some ‘O’ Levels and was admitted to Pembroke Grammar School. But that’s another story.

Words: Andrew Thomas

This article was first published in Pembrokeshire Life sadly no longer in existence.