Moelfre is a beautiful village, in a sheltered bay. It has a long history, yet one event still lives in the memory of Moelfre: the wreck of The Royal Charter.

October 2025 marked the 166 anniversary of the disaster. It has had a proud lifeboat station for many years. 100 years to the day after the loss of The Royal Charter they put to sea to rescue the crew of The Hindlea. It hit the same rocks – now called “The Royal Charter Rocks” – but this time all were saved.

They could do nothing in 1859. It was impossible to launch lifeboats in the “Royal Charter Storm.” The fiercest in living memory, a hurricane. 133 ships were wrecked, 90 were badly damaged. In conditions of such ferocity all ships were entirely alone.

![The Royal Charter [1] Moelfre and the Wreck of The Royal Charter](https://www.welshcountry.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2025/11/StateLibQld_1_186783_Royal_Charter_ship.webp)

The Royal Charter [1]

When Charles Dickens arrived to view the scene at the end of December 1859 everything was calm. He watched divers continuing to recover gold from the wreck, divers who had spent Christmas on the rocky beach, with roast beef and rum. In the days after the disaster sovereigns had been scattered over the beach like seashells but they had long since been collected.

It was quiet when we were there too. Just ourselves and a couple playing with their dog on the pebble beach below the holiday caravans positioned carefully for the splendid view.

It wasn’t what Dickens saw. He saw “masses of iron, twisted by the fury of the sea into the strangest forms.” He comments that no more bodies had come ashore since last night.

Although the wreck was only 25 yards from the shore it took months for the bodies to come ashore. There were so many of them. Perhaps 450. He expected that the spring tides would dislodge others still trapped in the wreckage. A grim harvest from an angry sea.

![The Royal Charter broke up on these rocks near Moelfre [2] Moelfre and the Wreck of The Royal Charter](https://www.welshcountry.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2025/11/MoelfreRocks-scaled.webp)

The Royal Charter broke up on these rocks near Moelfre [2]

Dickens had come to see the Rector of St Gallgo’s church in Llanallgo, at the top of the hill above Moelfre. This was Stephen Roose Hughes, another prodigious writer, a man who opened his house and his heart to distressed strangers. He was a true and unaffected Christian, “delightfully genuine”, with “noble modesty.” What he had done, with the help of his wife and of his brother, another clergyman, Hugh Robert Hughes, was worthy of recognition. Dickens travelled from London to offer his respect.

Stephen Roose Hughes became one of the heroes of the Royal Charter. His church, St. Gallgo’s is one of the oldest Christian sites in Anglesey. He turned it into a mortuary where he worked “surrounded by eyes that could not see him,” amongst dead strangers who someone else had loved.

And in the end he also became one of its victims.

You can read Charles Dickens’ admiration for Hughes in “The Uncommercial Traveller.” He tells us how Hughes examined ripped clothes and buttons, how he looked for distinguishing scars, crooked toes, tattoos. And all the time he was wrapped in the suffering and pain of others, seeking those they had lost so suddenly.

Their graves are scattered all over the north side of Anglesey, wherever the bodies washed ashore. They make the story of the shipwreck so horribly real. In Llanallgo there is the small stone for William Thompson from Cardross in Dumbartonshire who was an engineer in Hobart Tasmania. There is also a large chest tomb containing a family – James Davies and Louisa Francis and four of their children – twin daughters Sophie and Florence and their sons Walter and Derwent. The tragedy is still alive. The descendants of Marius Boyle, a miner who was lost, laid a memorial outside the door to the church for him in 2004.

![St Gallgo's Church, Llanallgo [3] Moelfre and the Wreck of The Royal Charter](https://www.welshcountry.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2025/11/St-Gallgo.webp)

St Gallgo's Church, Llanallgo [3]

At least they are named. In St Mary’s Church in Pentraeth there are stones paid for by Lady Vivien from Plas Gwyn. There are six small graves planted in a square. In the middle there is a larger stone erected in 1876. “Near this stone lie buried six bodies which were washed ashore in this parish.They shall be mine saith the Lord of Hosts in that day when I make up my jewels.”

The Royal Charter, built to bring Australia that bit closer, now lies beneath the sea. Much of the gold was recovered by those salvage divers in the months after the wreck. But it is still visited by divers, who still believe in treasure.

It didn’t get off to a good start. It was built in the Sandycroft shipbuilding yard near Chester for the Australian Steam Navigation Company. The launch in July 1855 inspired great interest, “on account of its vast proportions and the novelty of the construction of such a ship on the banks of the Dee.” It was a steam clipper, a hybrid ship, built of steel. It was a sailing vessel but with the addition of a steam driven propeller installed to keep the ship moving in calm conditions.

On 26 August 1859 she left Melbourne for the last time. There were about 371 passengers and a crew of 112. There was plenty of official gold on board. There was a consignment in the cargo – Captain Taylor signed a receipt for £322,440 of gold. But the passengers had plenty of their own, their personal fortunes carefully accumulated in the gold mines. Thus the true wealth on board can never be accurately calculated.

It was a tough voyage with bad weather throughout but the ship made excellent time. The Northern Times tells us that “the greatest happiness prevailed amongst the passengers,” and, in an act of some irony, “off Ireland a collection was made for a testimonial to Captain Taylor and a purse made by the lady passengers for Rev Mr Hodge of New Zealand, who had discharged the religious duties during the voyage.” In spite of the difficulties this was a record breaking run. Only 55 days to Ireland.

![St Mary’s Church in Pentraeth [4] Moelfre and the Wreck of The Royal Charter](https://www.welshcountry.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2025/11/Pentraeth.webp)

St Mary’s Church in Pentraeth [4]

Then on 25 October the barometer started to fall dramatically. The Captain did not put into Holyhead as Brunel’s SS Great Eastern had already done. He wanted to outrun the approaching storm and maintain the ship’s reputation for speed and service. It was 1.30 pm.

Off Bardsey Island the steam tug United Kingdom came alongside and asked if they would give a lift to eleven riggers on their way back to Liverpool. They boarded a ship heading for disaster.

Taylor signalled for a pilot to guide him into Liverpool from Point Lynas near Amlwch but it was impossible to reach the ship. The winds reached hurricane force and swung around from east to north east, driving the ship inexorably towards Anglesey. They tried to fight the sea with their steam engines but they were powerless. At 11.00 pm Taylor dropped anchor but within 2 hours their chains snapped. The crew frantically chopped down the masts to reduce the drag of the wind but it made little difference. Then the propellers stopped, possibly fouled by the abandoned rigging. She drifted powerless on to a sandbank. They fired rockets and distress flares but the storm was so fierce that those on the shore could do nothing other than watch. Boats were lowered but were instantly smashed.

On the ship things were grim indeed. The Captain tried to reassure passengers that they were secure now they were on a sandbank. They were so close to the shore that they were sure of rescue. But however he tried to re-assure the passengers, he knew things were desperate. He quietly sent one of the crew to smash all the bottles of drink in the stateroom to stop the crew drinking them. One of the few survivors described the scene. “Families were all clinging to each other; children were crying out piteously.” Reverend Hodge held a prayer meeting.

At this moment a crew member offered to swim to the shore in the boiling sea with a line. This was Joseph Rogers, although his real name was Giuseppi Ruggier, a Maltese seaman. His act of heroism was recorded by the artist Henry O’Neil in 1860 in a painting called “A Volunteer.” Although badly injured by the waves that crashed him into the rocks, he managed to take a line to the shore. As a result 39 men were saved. Women were reluctant to trust their lives to the bosun’s chair they rigged up. Crew members used it and joined in the rescue from the shore but no women or children were saved, though two boys aged 11 and 9 may have been washed ashore at Conwy, strapped to a plank and launched by their father.

![Survivor of the Royal Charter shipwreck Guzeppi Ruggier anglicised to Joseph Rogers [5] Moelfre and the Wreck of The Royal Charter](https://www.welshcountry.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2025/11/137217_WM-1976-6-Joseph-RodgersEDIT.webp)

Survivor of the Royal Charter shipwreck Guzeppi Ruggier anglicised to Joseph Rogers [5]

Just before 7.00 am on 26 October 1859 the rising tide picked up the ship and drove her onto the rocks just to the north of Moelfre. Winds of over 100 mph broke the ship in half. Passengers were “closed up in the jaws of death.” They fell into the sea with machinery and ironwork. In these conditions they had no hope at all. At the bow the crew were still desperately operating the bosun’s chair. At the stern the remaining passengers could only watch, separated from this fragile line to safety. Soon both sections were destroyed by the power of the waves. Iron work recovered from the wreck had sovereigns, and in one case a gold bar, driven into them as if it were clay.

No one really knows how many died or what the ship was carrying, for the Purser and his records were lost. It is believed that at least 450 died so close to the shore. It is said that many were dragged to the bottom by their money belts stuffed with gold before being beaten to death on the rocks.

Captain Taylor “succumbed to a sailor’s fate.” He was seen struggling in the water until a boat fell, hitting him on the head. He wasn’t seen again.

The men of Moelfre formed a human chain and reached out into the waves to rescue who they could. They became known as “The 28”, but in truth there was little they could do. The storm was sudden and it was shocking and then it was over. Their shoreline was covered in gold – and in bodies.

It was reported by the steamer Druid which arrived in Liverpool from Anglesey, having seen out the storm, that the wreck was being plundered and that the military had been dispatched to protect property. But there were also conflicting reports that everything found had been handed in to the Customs House agents who kept a record of it all. The truth probably lies somewhere between. One reporter says “I saw men picking sovereigns out of the holes of the rocks as if they were shellfish.” You can’t really blame them. There is a long tradition of gathering what you can from the sea. The militia from Beaumaris and an Army detachment from Chester arrived to protect the gold. Certainly the greatest part was recovered. But local knowledge is always crucial. Some was sure to have got away. And some scraps are sure to be there still.

There is a memorial Stone erected in 1935 above the rocks where The Royal Charter was smashed. It is on the beautiful Anglesey coastal path. You can stand by it and look down at the quiet sea as we did, beneath which the wreck still lies. Still visited by divers, who talk like fishermen of the big one that got away, of gold that appears and then slips away again in the tide. It is a skeleton of bulkheads and ribs that never changes.

It surrendered its dead slowly. Bodies were washed up on the beaches of Anglesey for weeks afterwards. Dealing with them was a mammoth task.

![Memorial Stone [6] Moelfre and the Wreck of The Royal Charter](https://www.welshcountry.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2025/11/Memorial-2.webp)

Memorial Stone [6]

Roose Hughes realised that something needed to be done, and something that preserved dignity and humanity in the aftermath of this shocking tragedy. He took the lead. The people were paid ten shillings for each body they brought up the steep track to the church of St Gallgo. It was not a great deal for such awful work. They were laid out in the church which became a mortuary. The furniture was removed and services held in the Church school which later also held the inquest.

Many turned up to find bodies of their loved ones. The visitors would speak to the Rector and offer some details. Then Roose Hughes and his wife would search the long rows of bodies. If they felt they had a positive identification, they would take the relatives in to the church blindfolded to save them from the horror of the scene. They would allow them only to see one particular body.

Many more wrote letters. Roose Hughes replied to every one of them. Yet sometimes there was little to say. Bodies were often battered beyond possible identification. Many had dressed in haste and were not wearing their own clothes. Sailors could sometimes be identified by their tattoos but it was harder with passengers. The presence of a receipt for the purchase of a parrot about which the family had heard in a letter was not always sufficient. Many parrots went down with the ship. But he did what he could, checking and listing possessions, and noting distinguishing features.

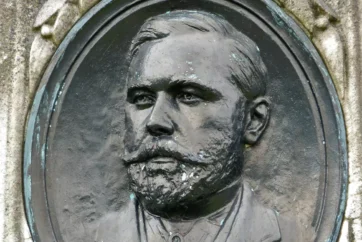

![Obelisk, St Gallgo's Church, Llanallgo [7] Moelfre and the Wreck of The Royal Charter](https://www.welshcountry.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2025/11/136758__MG_4227-Straightened-scaled.webp)

Obelisk, St Gallgo's Church, Llanallgo [7]

Roose Hughes realised that something needed to be done, and something that preserved dignity and humanity in the aftermath of this shocking tragedy. He took the lead. The people were paid ten shillings for each body they brought up the steep track to the church of St Gallgo. It was not a great deal for such awful work. They were laid out in the church which became a mortuary. The furniture was removed and services held in the Church school which later also held the inquest.

Many turned up to find bodies of their loved ones. The visitors would speak to the Rector and offer some details. Then Roose Hughes and his wife would search the long rows of bodies. If they felt they had a positive identification, they would take the relatives in to the church blindfolded to save them from the horror of the scene. They would allow them only to see one particular body.

Many more wrote letters. Roose Hughes replied to every one of them. Yet sometimes there was little to say. Bodies were often battered beyond possible identification. Many had dressed in haste and were not wearing their own clothes. Sailors could sometimes be identified by their tattoos but it was harder with passengers. The presence of a receipt for the purchase of a parrot about which the family had heard in a letter was not always sufficient. Many parrots went down with the ship. But he did what he could, checking and listing possessions, and noting distinguishing features.

145 bodies were buried in the small churchyard in graves of four and then exhumed and reburied when identification was possible. Sometimes Roose Hughes performed a funeral service twice over the same body. He saw all this as his duty.

He replied to every letter he received, offering comfort and understanding. He wrote 1075 replies. The effects on him were considerable. Dickens noted that he was “unable for a time to eat or drink more than a little coffee now and then, and a piece of bread.” He absorbed grief and pain and yearning and in so doing exhausted himself. It says as much on his grave.

His noble and disinterested exertions on the memorable occasion of the terrible wreck of The Royal Charter are well known throughout the world. The subsequent effects of those exertions proved too much for his constitution and suddenly brought him to an early grave.

![The grave of Stephen Roose Hughes [8] Moelfre and the Wreck of The Royal Charter](https://www.welshcountry.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2025/11/Roose-Hughes-2.webp)

The grave of Stephen Roose Hughes [8]

Today his church is neat and comfortable, recently restored after a serious fire, but the memorial is collapsing. The obelisk was raised by public subscription and was placed in the church but was moved outside in the early 20th century. The ground on which it stands is unstable and the obelisk leans and sags.

His grave, erected by his widow Jane Anne, was also neglected for many years but now restored, it rests behind its railings. A proper memorial to a hero.

He died on 4 February 1862. He was 47.

Words: Geoff Brookes

Images:

Feature image: Geoff Brookes

[1] Item is held by John Oxley Library, State Library of Queensland, Public Domain, Source

[2] Rhion assumed (based on copyright claims), Public Domain, Source

[3] The People’s Collection, CAL, Source

[4] Geoff Brookes

[5] The People’s Collection, CAL, Source

[6] Geoff Brookes

[7] The People’s Collection, CAL, Source

[8] Geoff Brookes