Geoff Brookes tells the tale of Laura Ashley, pioneer of the infamous Laura Ashley Welsh textile design company.

It was her sixtieth birthday; she did not want any fuss, just a quiet night in. She went to bed, got up in the night and in the darkness of her daughter’s house, fell downstairs. Quite simple and quite tragic. She died after nine days in a coma. The Dowlais Male Voice Choir sang at her funeral in Carno.

For centuries very little happened in Carno in Powys. In that way, it is no different to many other small communities in rural Wales. Perhaps there had been a legendary battle between two sons of Hywel Dda in Cwm Nant y Penglog, the valley of the stream of the skull. Perhaps it is just a story. But what is undoubtedly true is that for a brief period of time, Carno was famous throughout the world and that was because of Laura Ashley.

Today you can find three slate graves in a neat row in the churchyard of St John the Baptist by the side of the A470, facing the softly wooded hills. To the right is the grave of Laura Ashley, the first to die in 1985. Next to her is Bernard, her husband, and to the left, his father Albert. Simple, uncomplicated graves, all carrying the name of an iconic brand, an international label. One of the world’s most famous companies, and for so many years it was based in Wales.

Laura Mountney was born in Dowlais, near Merthyr Tydfil in 1925, and was educated there and in Croydon, returning to Wales as an evacuee during the war and attending Aberdare Secretarial School. She also served in the Women’s Royal Naval Reserve as a teleprinter and was one of the first women to be sent to France after D-Day. She married Bernard Ashley in 1949 and worked as a secretary for the National Federation of Women’s Institutes. This organisation played a key role in the genesis of the Ashley brand through an exhibition of traditional handicrafts at the Victoria and Albert Museum in London.

Laura and Bernard were inspired to assemble their own screen printer. They bought some dyes and linen and started creating small patterns on squares of fabric in response to the small space in which they were working – their kitchen table in Pimlico.

Laura Ashley designed clothes for mothers to wear at home, stitched initially by women in their own homes in mid Wales.

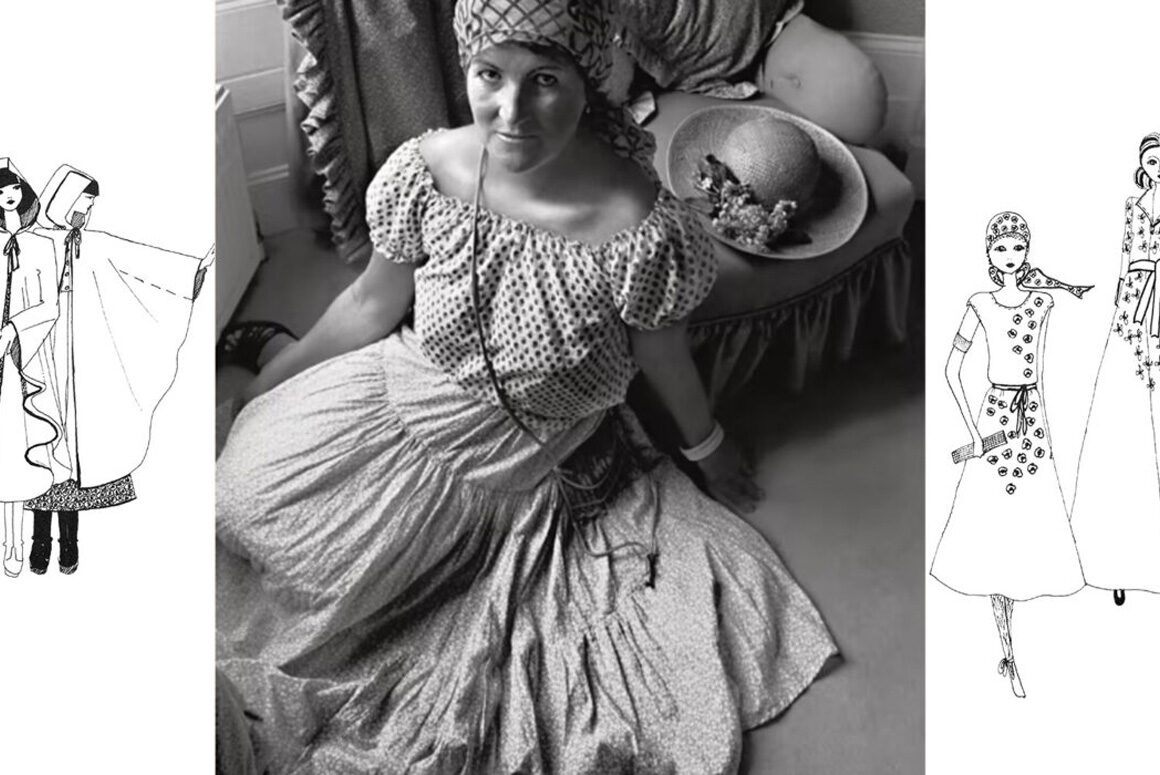

The floral patterns came to represent a type of Englishness, a suggestion of sunshine on the lawn outside an elegant Country House perhaps. Natural fabrics, Victorian high necks, full sleeves, lace and ruffles, smocked pinafores and long, flowing dresses. A fantasy of a time that, if it existed at all, was never so clean. But the clothes they sold were always very distinctive; instantly recognisable, which is the most important thing you could ever say. Laura Ashley once said, “living quite remotely as I have done, I have not been caught up with city influences and have just developed in our own way.” She sold a dream which perhaps expressed a yearning for an apparently simpler past. She unconsciously tuned in to the spirit of the times, a neo – Victorian fashion template for a life of self-sufficiency in the country – like her own life in mid Wales with four children.

It worked. It brought enormous wealth and the presence of a global brand had a huge impact on the economy of central Wales.

Soon, it was evident that an enormous shift was taking place. A company that was in some ways anti-fashion, became the fashion itself, creating the trends. She drove the switch from mini to maxi for example. She was able to create an image of permanence in the bewildering world of fashion trends, maintaining apparent truths about how women should look. She believed that women looked their best at the end of the nineteenth century and so her clothes use more material, not less – covering up and suggesting, rather than exposing and revealing.

In 1968 the first shop opened in south Kensington. Initially business was slow, but advertising on the Underground brought a sudden and sustained increase in turnover. By 1970 a branch in Fulham Road sold 4,000 dresses in one week. They surfed on waves of success throughout the seventies. Shops were opened in major cities across the world, starting with Paris in 1974.

The Laura Ashley style evolved too, it embraced perfume, home furnishings, interior design; integrating patterns to coordinate fabrics, wall paper and tiles.

Bernard Ashley once said, with a sense of awe it seems to me, that Laura had “dressed the women of the world as milk maids.” Quite an insight. Except that real milk maids were never quite so self-consciously polished.

Laura apparently turned down the offer of an OBE, allegedly upset that it hadn’t also been offered to Bernard and perhaps because she recognised what a blow it would be to his ego. She did accept a Queen’s Award for Export in 1977 and he was eventually knighted in 1987, two years after her death in 1985.

She died when the company was about to float on the Stock Exchange. When it happened, shares were 34 times oversubscribed as investors tried to invest in the dream. But sadly the company soon announced a loss and the value was suddenly halved. By 2001 the family had lost any connection with the business.

Bernard Ashley died of cancer in 2009. During the war he held a commission in the Royal Fusiliers and was seconded for a while to the Gurkha Rifles. After that seminal moment in the Women’s Institute exhibition, he gave up his job in the City and became the business man at the heart of the Laura Ashley brand. Originally, he designed the printing equipment and Laura remained responsible for the design until just before her death. Their partnership, with their skills complementing each other perfectly, gave the company a strength and a purpose.

Bernard (or BA as he was known and remembered on his gravestone) was sometimes described as “flamboyant.” Obituaries described an intimidating bully who expected Laura to do as he wanted. He certainly felt that the world was a better place if he had his own way. There is talk of a combustible temper which was displayed regularly when he smashed wine bottles. They say he once threw a fridge downstairs. They say he ripped the phone from the wall so often that eventually BT were reluctant to reconnect it. They say he described his wife as a “husband keeper” and seemed aware that life with him was not always easy. What is clear is that Laura had the judgement and the vision; he had the drive that translated it into success.

But it could not last forever.

In the world of fashion, fashion changes. The Laura Ashley brand of anti-fashion was over taken by designer labels. Those humble beginnings on a kitchen table are now commemorated on a plaque outside 33 Cambridge Street in Pimlico, and neither should anyone forget how, from a base in mid-Wales, Laura Ashley reached out to touch the world.