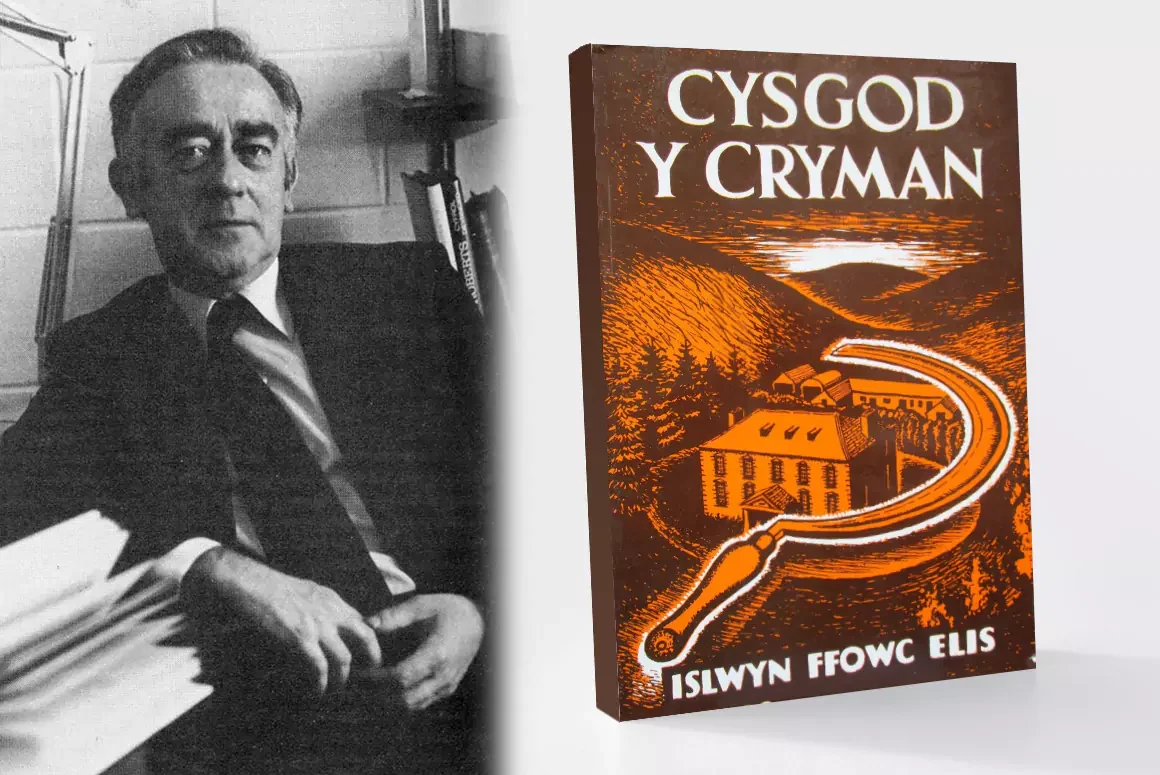

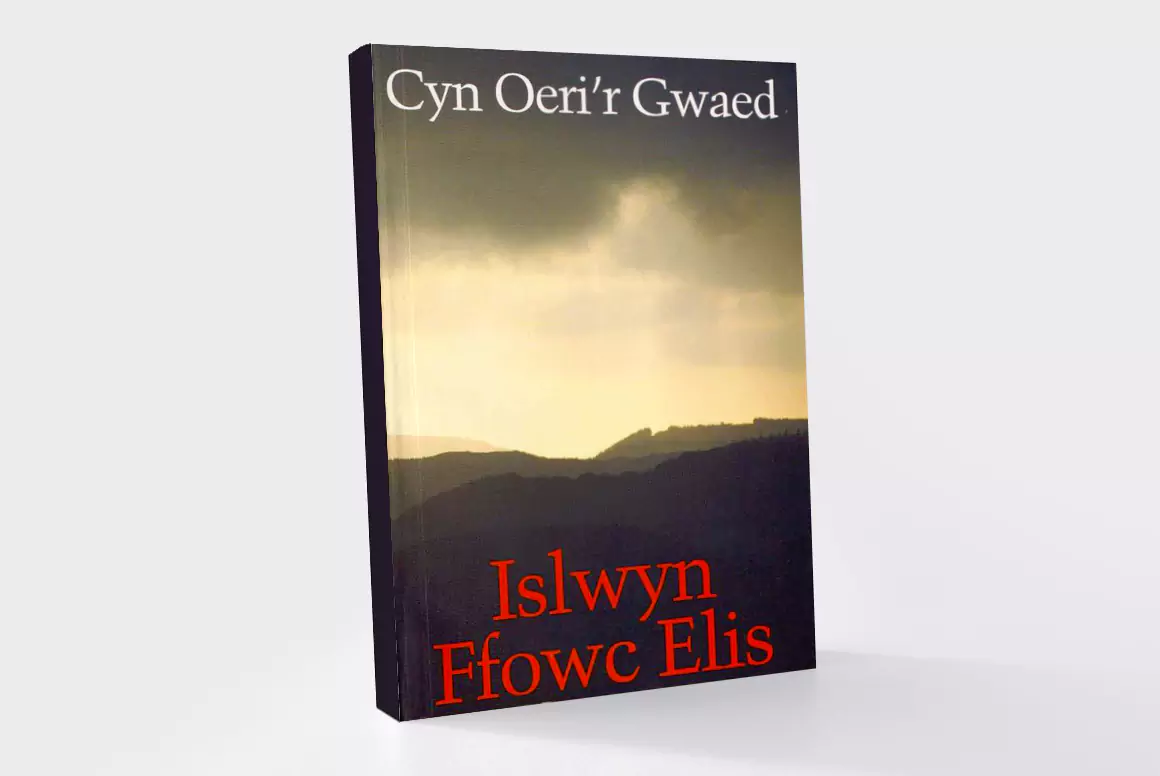

November 17, 2024, was the centenary of the birth of Islwyn Ffowc Elis, one of the most popular Welsh prose writers of the twentieth century. In 1947 he won the crown for poetry in Lewis’s Eisteddfod in Liverpool, and then in 1951 he won the prose medal at the National Eisteddfod for a collection of personal essays, Cyn Oeri’r Gwaed (Before the Blood Runs Cold). Upon its publication Thomas Parry stated, “Megis ar un sbonc fe neidiodd yr awdur i rywle pur agos i reng flaenaf llenorion Cymraeg.” (“As if in a single bound the author leapt to somewhere very close to the highest rank of Welsh writers.”)

Elis’s first novel, Cysgod y Cryman (Shadow of the Sickle) was published in 1953. In 1999 it was selected by the Arts Council of Wales as the most significant Welsh-language book of the twentieth century. This book and its sequel, Yn Ôl i Leifior (Return to Lleifior, 1956), both set on the fictional farm Lleifior, explore the complex of relationships between capitalism, socialism, and communism. A time-travel fantasy set in 2033, Wythnos yng Nghymru Fydd (A Week in Future Wales, 1957), contrasts a utopian vision of an independent Wales with an alternate scenario in which Wales has become “Western England” under autocratic domination. In a famous and particularly moving scene, Elis depicts the death of the last native Welsh speaker.

To list all of Islwyn Ffowc Elis’s novels, hundreds of short stories, essays, and articles would take more space than we have available here. Instead, I recommend that you find a copy of any of his work, sit down with it, and enjoy one of Wales’s most influential modern artists and thinkers. For those who don’t read Welsh, a number of his novels have been translated into English, but for language learners I recommend trying the original, even if you need to keep a Welsh dictionary close at hand.

To list all of Islwyn Ffowc Elis’s novels, hundreds of short stories, essays, and articles would take more space than we have available here. Instead, I recommend that you find a copy of any of his work, sit down with it, and enjoy one of Wales’s most influential modern artists and thinkers. For those who don’t read Welsh, a number of his novels have been translated into English, but for language learners I recommend trying the original, even if you need to keep a Welsh dictionary close at hand.

Cyn Oeri’r Gwaed has not, to my knowledge, previously been translated into English. I am, therefore, pleased to offer below my rendering of the first essay in the book, which introduces us to Islwyn as a child and as a young man.

Adfyw / Reminiscing

from Cyn Oeri’r Gwaed by Islwyn Ffowc Elis

(Translated by John K. Bollard)

Er cof am Islwyn ar ei ganmlwyddiant.

In memory of Islwyn on his 100th birthday.

The sun has risen nine thousand times since I first saw it. It doesn’t know that. It doesn’t know, either, how many of its sunsets I have kept, or how many starry nights after it sank below the earth. I have gazed upon them and stored them where there was no moth or rust to corrupt, or anything, except old age, and where there were no thieves digging through them, except death. And tonight I will take the key and go to the storehouse door, and pluck the tapestries and the curtains from the dust.

Just a word or two over the colours, before folding them gently and putting them back. Just a glimpse, very, very slyly.

I was a rather frail child, I realize. Not a great player, no expert at kicking the ball. A sort for sitting idly and daydreaming, and because I was so feeble and so good-for-nothing at sport, I saw myself as a hero and a terror to savage tribes, as a captain of ships, and shooting hosts of lions. Needless to say, the Union Jack was the flag of my childhood, English was the language of every adventure, and the far corners of the British Empire were the far corners of my dreams. But the change of my flag, my language, and my loyalty has not changed any of the romance of that childhood. The childhood when I played in front of the house in Glyn Ceiriog, between the columns of the little verandah, playing house with dishes, just like a girl. But in those blessed days, playing girls’ games or wearing a smock was not scandalous. That was before the beating and the cuffing; before the days of the gang.

We called it a verandah; but it wasn’t anything but the loft that came out over the garden, in the pleasant little shade above the blue pillars. And the stair descending to the road between the lavender and the lily-of the-valley and the little crooked gate wasn’t enough to keep a child from the perils of the road. I sat there a hundred times, after the days of the smock and the little dishes, through the years of boyhood and youth, on summer Sunday afternoons. There was a bench there, an old bench with arms, and when it was warm and the heat was shimmering on the village roofs and on the tips of the hay, I’d sit between those brown arms to dream. Gazing across the valley over the wool factory and the terraces where they would put out the flannel to dry, gazing at the hill opposite, asleep under its heather. And the swallows darting about and chirping together, in restless hundreds between us and the hill beyond. I hear their chirping still.

I didn’t have much love for learning. Much love for school. School was a sort of prison for me. But school was in the Nantyr valley, there was no prettier one in Wales, a tiny school with a front entirely of glass. And when it was fine and summery, lo, the glass walls opened and put the school in the fresh air. I have forgotten much that I learned in that modest little school, but one thing I learned will not leave me as long as I live. It is likely that’s because, as they say, it is bound up with my language and my background, alive in my lifetime. That one thing was a wreath of lyrics, and those were Welsh lyrics, which continue to throb in my memory every spring and beginning of summer.

It was a mile and a half to school, through sun and rain and snow – no mention of either bus or car – and the wind cutting into the ears and the little legs. But I saw those days in the wooded green vale, I saw the dew turn into pearls and the heather into fire. And I recited those lyrics while loitering by stream and stile, and I asked God to make me a poet, too.

Beth a welais ar y lawnt What did I see on the lawn

Gydag wyneb gwyn edifar? With a sad, white face?

Beth a welais ar y twyn? What did I see on the hilltop?

Wyneb oen, y cynta’ eleni. The face of a lamb, the first this year.

And I imagined, while reciting them, that the primroses were listening and the goslings nodding their heads.

Glas yw wybr Ebrill, The April sky is blue,

Glas fel llygad Men; Blue like Men[na]’s eye;

Mae enfys ar y cwmwl There is a rainbow in the cloud

A blagur ar y pren. And buds on the tree.

Where is that rainbow, I wonder, that I first spoke those lines about while gazing at it? And what became of the buds on the rowan-tree in turn?

Gwn ei ddyfod, fis y mêl, I know it will come, the honey-sweet month,

Gyda’i firi yn yr helyg, With its merriment amongst the willows,

Gyda’i flodau fel y barrug, With its blossoms like the frost,

Gwyn fy myd bod tro y dêl. Blessed will my world be when it comes.

Onid yw’r caeau yn wyrdd, yn wyrdd? Aren’t the fields green, green!

A melyn eithin And gorse yellow

Dan haul Mehefin Under the June sun

Hyd fin afonydd a min y ffyrdd. Along the riverbanks and the roadsides.

I was at times in the vale of Porthmadog, and there trying to connect the fields and the slopes with the poems that were sung there. But in vain, completely in vain. The poems had remained in the Nantyr valley, in the hedges and the hillsides and in the wary turns in the road. And no one could ever take them away. And you must forgive me, spirits of Gwynn Jones and Islwyn and Dafydd ap Gwilym, when I say that of all of you my first love and my most unqualified was Eifion Wyn[1].

I went then to Llangollen school, a valley of history and beauty and an eisteddfod with singers of the world. I learned there a bit of English, I learned the miseries of exams. One morning the boys found out that I was a Welsh nationalist, and I was put headfirst into the wastebasket. The result of that treatment was to make me a fiery nationalist. In Llangollen I began to write – passionate stories boiling with adolescence, and awkward poems, so clumsy that the Cocos himself would blush before them.[2] But the green patches of those six lonely years were escape to the heather of the hills in maths lessons, and escape body and all to the harvest of hay and corn. I can still hear the rattling of the cart on its journey to the yard, the hay scraping the hedges, and waiting for them in bundles, and the dew softening the stubble; there are red bars in the western sky where the sun was; there is the pure exhaustion of the body and the kettle humming on the fire; there is the land going to rest in the ancient stillness of the evening. These are the strong days that united my flesh with the earth.

And then came the days of Bangor. There never was, and there will never be their like. If the gardens of Babylon were given to me, or the countless millions of Rockefeller, I do not believe today that I would exchange them for those five intoxicating years. The Menai was blue and tempestuous, the Springs went through Sili-wen, and I never counted them.[3] There friends were made and lovers lost, leaving the school of agnosticism and learning faith.

Those were days of war. The number of students was small, and half of them were tall Englishmen and they were very loud. There was a crisis in Welsh life; the crisis went into our veins, and we clung tightly to each other. There was never such singing, no indeed, by the nightingales of the Rhondda as our singing in that time of crisis. Gathering in excited crowds, and the song venturing from the depths of some lone tenor or mellifluous soprano, and swelling until everyone is mesmerized. In the blind streets of the blackout, in the mornings of interrupted lectures, here, there, everywhere—the singing kept Wales alive in the stone college. And when we caused a commotion, and the song rose up in triumph, the English around us grew silent and became mute. Some would admire, some would frown, but all became mute. A kind of awe before the power of the singing that made Wales Wales.

And the renaissance that Bangor saw those years. National bards, philosophers, statesmen and comedians, pioneers in entertainment and learning—there they were nurtured. Each winter a handful would sniff their way to one of the messiest rooms in the college, and, after sitting in complete discomfort on the wooden benches, begin to think. And in those sessions, create marvellous follies. The songs that were created, the music that poured out, the fantasies and the skits, moulded into musical dramas that were christened “Nirvana Roundabout”, “Huw Huws’ Dream”, “The Magic Carpet”, “Glyndwr-itis”. And performing them shamelessly, and playing the fool in them, our peerless progeny. If Bangor sees their like again, blessed will it be.

But there were also times of silence. A student is not all noise. The agonizing nights before the summer exams, and the town in a sinister silence, except for the bleating of various frenzied students crying, “Too late! Too late!” Flitting from book to book like a moth, and failing to get any nectar. Getting up and walking round the block and back, and the cathedral clock announcing the passing of the hours with relish. Feeling the hysteria rising in the nerves and blood, staring and staring until each letter splits in two. And the call of the June cuckoo and the smell of the hay in Glyn Ceiriog so far, so hopelessly far away.

But those nights were not in vain. If they had not been, I would still not have seen one of the most beautiful scenes in my life. There were three of us in the grip of the books around the table, and midnight had been gone for some time. One went to bed cursing education miserably. The other and I laboured on and on. And at three o’clock in the morning getting up and stretching, and one opening his swollen eyes and saying,

“What about going for a walk?”

“What, now?”

“Yeah, c’mon.”

And slipping through the door like mice, and slinking along the wall, and at the corner, standing. Menai was like a sheet of silk with a heavy ball of a moon quivering in its midst, and Môn in pale hypnosis under the other moon above. A silence came upon us, and we walked between the trees that were tall and quiet and full of summer. And falling on our faces on the warm, white road with its surface a myriad of little holes oozing tar. We were there quite a while slumbering, and our blood rushing, bewildered, like poets and fools and fluent in Hindustani. There are faults in the educational system, and those are undoubtedly numerous, but it gave a chance one night for two students to be divinely foolish.

I could go on to Aberystwyth, where I listened credulously at night for the bells of Cantre’r Gwaelod in the water. I could go to Bala Lake, where I could see the Aran, with its head down in a cornet of snow. But now I must gather the colours and put them back. Things grow pale in the light of day. Yesterday is done, like the bones of some Pharoah turning to dust at a touch. But it was delightful to see them and to feel them. And before the sun rises nine thousand times again, there will be more to put into the storehouse where there is no moth but old age, no thief but death itself.

Words © John K. Bollard

[1] Eliseus Williams (Eifion Wyn; 1867-1926) was a poet from Porthmadog, the author of Telynegion Maes a Môr (1906), from which the poems above are taken.

[2] John Evans ‘Y Bardd Cocos’ [the cockle-bard] (1827?-1888) was an eccentric, barely literate cockle seller from Menai Bridge whose verses were famed for their lack of rhyme, reason, and scansion.

[3] Siliwen is a road and a wood along the Menai in Bangor.