![]()

Geoff Brookes shares with us the story of Richard Robert Jones, a man regarded as eccentric, enigmatic and downright odd.

He was known as Dic Aberdaron and the North Wales Express said of him “Among the singular characters which nature sometimes produces… few have been more remarkable than Richard Robert Jones, of Aberdaron, in Caernarfonshire, who although an excellent linguist, is, in almost every other respect, an idiot.” Harsh words perhaps, but the newspaper had no fear that their victim would object to their assessment, because Dic Aberdaron lived in his own insular and peculiar world.

He was called Richard Robert Jones and was born in Morfa Llwyn Glas, about two miles from Aberdaron, at the far end of the Llŷn Peninsular in 1780 and achieved fame – or notoriety – for his unusual facility with languages. Today we would say that he was a savant, someone with an autistic disorder who displays exceptional ability in one particular area. His father was a carpenter who owned a small cargo boat and shuttled between Wales and Liverpool, but any hopes he may have had of passing on the business to his son were lost in the strange tidal forces of his son’s unusual mind. Dic’s apprenticeship was an abject failure. He had no practical inclinations at all and found it easy to neglect his duties. His father used to flog him regularly for reading on the boat instead of watching the tiller but such retribution was futile. Dic had a consuming mania for learning languages. In response his father, perhaps understandably, regarded him as a waster. Dic’s interests and his inability to engage with the daily obligations of rural life clearly exasperated him.

His formal education had always been sporadic and it was not until he was nine years of age that he was able to read the Bible in Welsh. He apparently found it very difficult to learn English but once he had a basic understanding, the floodgates seemed to open. At the age of 10 Richard began to study Latin and soon he acquired Greek, closely followed by Hebrew, Chaldaic, Arabic, Persian, French and Italian. In the end, without the help of education, Dic Aberadon could converse in thirty five languages, considerably in excess of the number required for daily life in North Wales.

“At the age of 10 Richard began to study Latin and soon he acquired Greek, closely followed by Hebrew, Chaldaic, Arabic, Persian, French and Italian.”

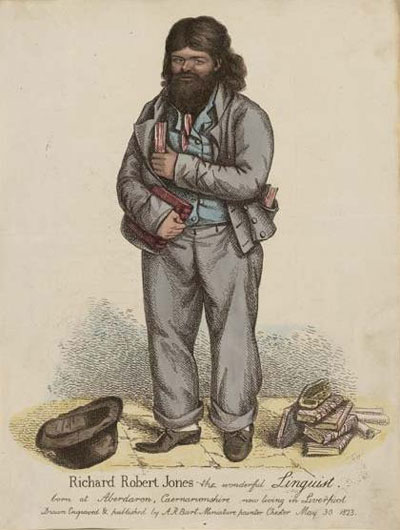

He left home to escape beatings from an exasperated father and spent much of his life in transit, learning different languages. He had a thick beard, a shapeless hat, often wore an old Dragoon’s jacket and travelled the country with his books and a succession of stray cats, wandering from country house to parsonage looking for support and arguing with inn keepers who were foolish enough to give him lodgings. He always carried with him a large number of books which he decorated with prints of cats cut from old ballad sheets.

Sometimes he had to sell books to buy food but he would always try to buy them back with any money he received. On one occasion he had to part with a precious Hebrew Bible which he was subsequently unable to recover so in 1807 he went to London to buy another. He ended up in Dover where he worked sifting ashes in the Dockyards. He was fed and given a chest in which to hold his books. He stayed for three years, and received instruction in Hebrew from a local Rabbi, which was probably more important to him than his pay of 2s 4d a day. His time in Chester a few years later was less distinguished. He was a complete nuisance and upset the residents by wandering through the streets, constantly blowing a ram’s horn. Although his favourite author was Homer, he particularly enjoyed singing psalms in Hebrew, whilst accompanying himself on a Welsh harp which he had been given and repaired.

He spent a lot of time living on the streets of Liverpool where he was a familiar figure, always with a book under his arm, not noticing or speaking to anyone. Dic was found on St. George’s Pier Head by the radical poet and abolitionist William Roscoe who was fascinated by the books spilling out of his clothes and then shocked by his ability to hold an informed conversation about ancient linguistics. Roscoe wrote a biography of him and went on to give him a small allowance which brought him some stability for a while and a room on Midghall Street. With his support some of his work was published, though it was all rather esoteric, including for example a Latin Treatise on the music and accents of the Hebrew language. But soon he was tramping around the countryside again.

He had little regard for his personal appearance which was described as “disgusting and offensive.” It was said that he was “filthy in the extreme and his hands resemble in colour the back part of a sole,” which has always been an image that has appealed to me. His clothes were threadbare and included “a nasty rag, which may once have been white and is probably still intended to represent a shirt.” His clothes were stuffed with books, “surrounding him in successive layers, so that he was literally a walking library. These books all occupied their proper stations, being placed higher or lower according as their size suited the conformation of his body, so that he was acquainted with each, and could bring it out when wanted, without difficulty.”

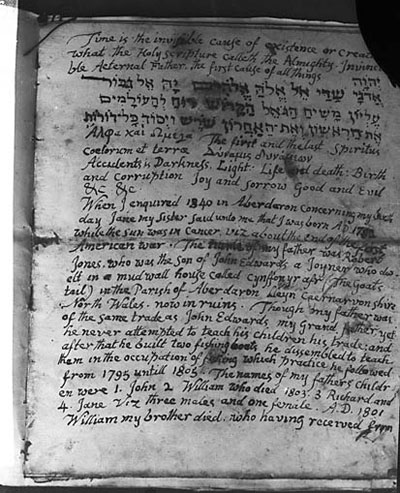

He turned up at the Beaumaris Eisteddfod in 1832 with an essay he had written in ancient Greek on the three versions of the ancient harp. Since there was no competition requesting entries on this subject, he could not be awarded a prize. There was undoubtedly an obsessive element to his character. His magnum opus was his Welsh-Hebrew-Greek Dictionary, a book he worked on for two years and which had by definition a limited appeal. The only copy is now in the National Library in Aberystwyth where you can also find Dic Aberdaron’s handwritten autobiography. Examples of his handwriting on their website bring you so much closer to this strange man.

There was in, some ways, pointlessness about his learning. It was pure in the sense that it was learning for its own sake because it benefited no one, least of all Dic. He learnt all those ancient languages which he was never able to use and acquired knowledge that he could never successfully share. Some regarded him as shiftless, with only a partial intellect “displaying the most remarkable want of capacity on every other subject.” He received much more generous understanding and freedom than perhaps he would have received today, when he would have been assessed, judged and treated. But in his own time his oddness brought with it a sense of mystery. Certainly the press were fascinated by what he represented. It was as if he had been touched by a divine influence which set him apart from others. They were wary of him as a consequence. There are elements that we can see in him that might today support a diagnosis of autism or Asperger’s Syndrome. He was argumentative and difficult and not too keen on other people. And perhaps in a way his talents were a curse – a barrier to proper engagement with the world and with other people.

In later life he returned frequently to St Asaph. Bishop Carey was very supportive and in fact was ready to do more for him, had not Dic been so independent. He used to lodge at the back of the George Inn in High Street, and it was there that he died in December, 1843 as penniless and alone as he had lived, and was buried in St Asaph Parish Churchyard.

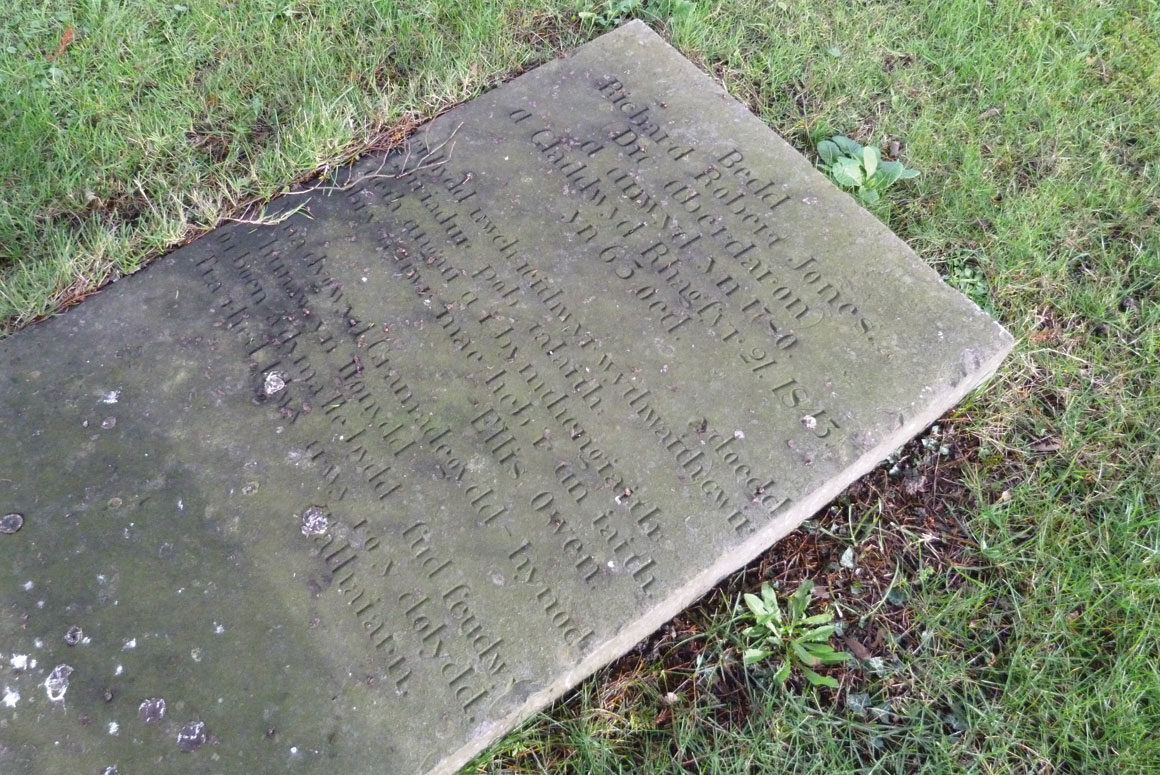

He was an important and unusual figure in his own time but is generally forgotten today, unless you are studying the work of R.S. Thomas, who wrote a poem about him. He is however remembered on a gravestone provided by residents of St Asaph, which you can find quite easily, lying flat in the grass close by the railings where there is a recently installed blue plaque on the corner of Lower Street.