When I asked about the tomb in the Cathedral no one seemed to know anything about it. Never really taken much notice of it I suppose. Just one amongst many. In the graveyard the great and the good of Brecon were surrounded by the falling leaves of autumn. It is a large and imposing tomb. Well proportioned. Solid. In its time it meant something. It was an acknowledgement of what he had done. Yet today it is neglected, ignored. The children from the school, laughing their way along the path close by, were not much troubled by him at all. I watched them as I kicked through the leaves. They were concerned only for life, not for the death all around them, as they called to each other carelessly and made their way home through the grounds of Brecon Cathedral. And why shouldn’t they? Their lives are in front of them; they have so much to look forward to.

Charles didn’t feel that way. And there is something very affecting about the life and death of Charles Lumley, I think. Something that troubles me. For he tumbled into darkness. Charles Lumley, VC. An early victim of post traumatic stress disorder.

There are life-changing moments for all of us I think. The trick is recognising them; many of us don’t know they’ve happened until it is too late. Perhaps Charles did realise that nothing would ever be the same again. For Charles, his life changed in a moment of bravado.

Charles Lumley was a military man. The details of his early life are sketchy and open to some debate, but the most reliable information would suggest that he was born in Kidbrooke in Kent around 1824, the son of a merchant. In 1841 he appears in the census as a gentleman cadet at the royal Military Academy in Woolwich and then, 10 years later, he is a soldier living with his mother at Shooters Hill. When he was married in 1852 to Letitia Beaulieu in Marylebone, he was described as a Lieutenant in the Army in the Earl of Ulster’s Regiment. So far, so good. A career soldier.

And then in 1854 he was posted to the Crimea.

The Crimea was an awful place, a genuine fore-runner for the trench stalemate of the First World War, just as bitterly cold, just as muddy and just as deadly. The triumphs of the Napoleonic wars were a distant memory. The army appeared incompetent and disorganised, particularly when compared to their allies, the well provisioned and efficient French. The British soldiers felt neglected and forgotten. 5,000 died in battle and 16,000 died of diseases like cholera.

The tomb of Major Charles Henry Lumley VC in Brecon Cathedral cemetery

The war itself ended in stalemate and those great battles, remembered in the names of rows of terraced houses, like Alma, Inkerman, Sebastopol and Balaklava were inconclusive.

But as always, amongst all this hopelessness and incompetence, there were individual acts of heroism which were recognised in the recently inaugurated Victoria Cross. And one of these was carried out by Charles Lumley.

The key strategic feature in the war was Sebastopol. To succeed the allies needed to take it from the Russians, but they had fortified the city and had strong defensive positions.

Their trenches were getting closer and closer to the city but the only way the allies could take it was in a direct frontal assault. After a bitterly cold and cruel winter when an inadequately provisioned army had shivered and died, the time had come they felt for a quick and decisive victory. Sebastopol had to be taken. The British were to attack a defensive feature called the Redan, against which their efforts had been directed throughout the summer of 1855. The French were to attack a defensive redoubt called the Malakoff.

The Russians came under heavy bombardment for three days prior to the assault. Over 13,000 shells were fired, though to little effect. When the British troops launched their attack at dawn on 8 September 1855 the defences were still intact. The Russian fire was very heavy but they still managed to fight their way into the Redan using scaling ladders. The dead and wounded were falling down these ladders as others fought heir way up, so it was impossible to get soldiers on to the Russian parapet in sufficient numbers.

One of the first officers into the Redan was Lieutenant Charles Lumley. As he reached the parapet he could see three Russian gunners reloading their field gun. He attacked them single handed.

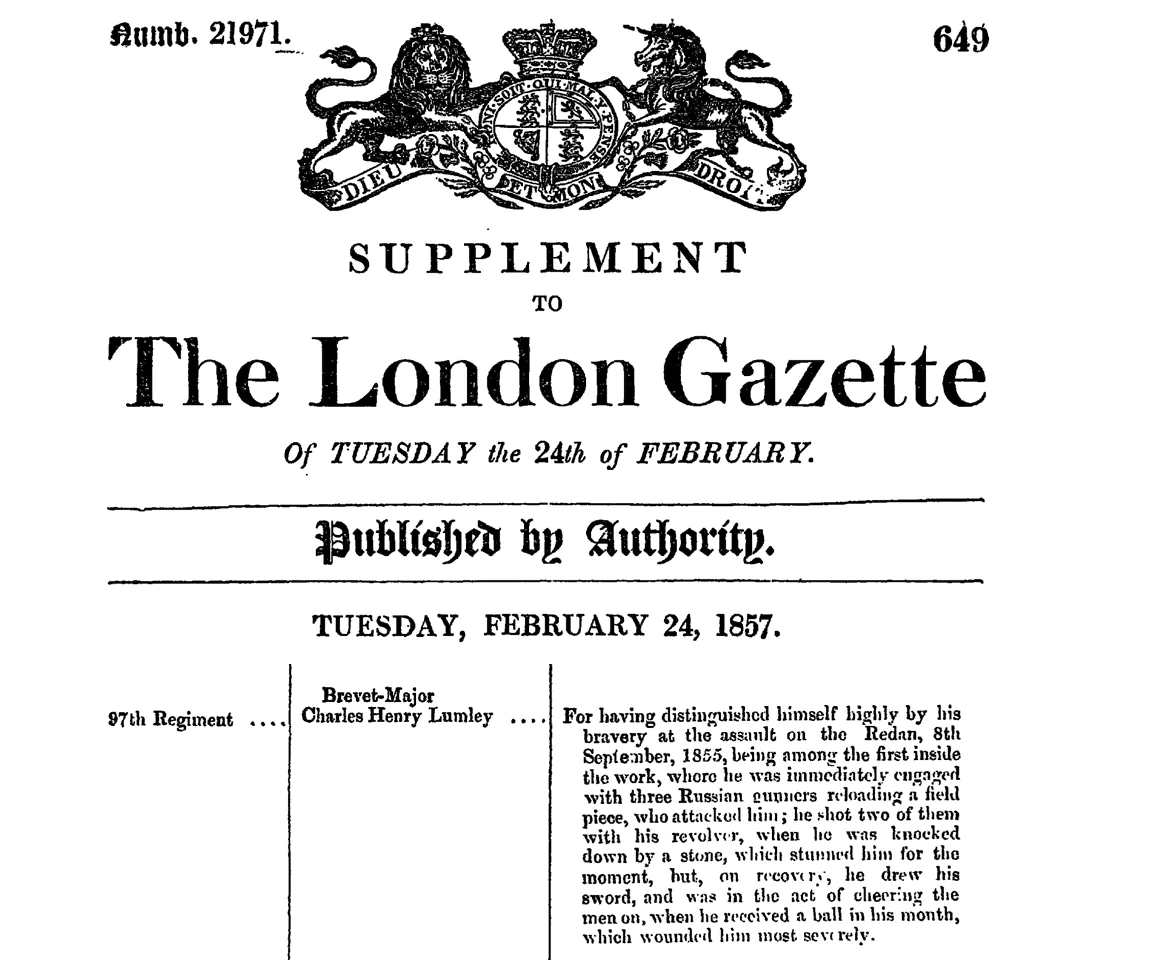

You can read his citation for the Victoria Cross in the National Archive, as it appeared in the London Gazette in February 1857.

The stone that hit him was most likely to be a handful of small cannon shot thrown by a desperate Russian who had no time to load his gun. It obviously worked, for it knocked Lumley to the ground. Perhaps it gave him time then to load his gun. The subsequent bullet in the mouth was of course most effective.

It was a severe wound, although not fatal and he was taken back from the Redan to the British lines for treatment.

The rest of the troops withdrew in confusion, despite the best efforts of their officers to rally them, and the Russians held the Redan. The French attack on the Malakoff however, was successful, which did little for British morale.

Charles Lumley was sent home on 29 September 1855. It was up to others now to play out the final few months of stalemate.

Earlier in the year Queen Victoria had met returning wounded. She wrote in her diary for 22 February 1855.

“We saw 26 of the sick and wounded of the Coldstreams. There were some sad cases: one man had lost his arm at Inkerman, was also at the Alma, and looked deadly pale – one or two others had lost their arms, others had been shot in the shoulders and legs, several in the hip joint…I cannot say how touched and impressed I have been by the sight of these brave, noble and so sadly wounded men and how anxious I feel to be of use to them, and to try and get some employment for those who are maimed for life. Those who are discharged will receive a very small pension but not sufficient to live upon.”

Depiction of the Siege of Sebastopol

The situation for Charles Lumley was no different. Bravery and suffering cut little ice. Although Charles’ actions had been recognised and he was promoted to major, he was still put on half-pay until he could find a new position. The Queen’s evident concern had not impacted upon the army authorities. But, along with the others decorated for their heroism on that day at the Redan, Lumley attended the first VC investiture in Hyde Park in London on 26 June 1857. He was a hero just like the others. But he was a changed man. His wound had profoundly altered his disposition and his outlook. He was a much troubled man.

He was appointed to the 23rd Regiment of the Royal Welch Fusiliers in 1858 and was stationed in Brecon. The appointment did not go well. He found the work difficult and felt that administrative duties prevented him from being an effective commanding officer. He was eccentric and hot-tempered. Matters came to a head on Sunday 17 October 1858.

He had had a difficult weekend. On the Saturday he was behaving oddly. He called his adjutant Richard Davies to his room on a number of occasions but each time there was nothing that he wanted. In the afternoon he and Letitia had planned to ride but the groom was not available. He flew into an enormous rage. Later when Davies brought him tea he refused to drink it and instead walked round and round the barrack square. He was still there when Davies went to bed at 10.00 pm.

On the Sunday morning he suddenly called out the guard which he had never done before. He was obviously very agitated. Davies reported that he kept going to the rear of the Officer’s Quarters and then returning.

“He was looking at me in a very strange manner. His look that morning frightened me.”

Mrs Lumley went off to church, as did Davies. Charles was not there when they returned. Letitia noticed that his pistol was missing. She sent Davies to look for him.

He didn’t have to go far.

He was in the toilet with the door closed though not locked. He was lying on his left side, holding the pistol in his left hand. He had clearly turned his head to the left and shot himself “two inches behind the right ear.” A single pistol ball was recovered from his brain. Although he was not dead when Davies found him, he died a few hours later.

Poor Charles. An inquest was held on the 25 October which decided that he had taken his life “whilst labouring under temporary insanity.” Obviously his mind was disturbed. But for how long had it been so?

When you look at his story it is clear that the events at the Redan had changed him. A serious head wound had caused a black cloud to settle over Charles Lumley that would not go away.

He felt compelled to complete what the Russians had started three years before.

It is not only here that he is remembered. His name appears on Letitia’s headstone in Bath, where she lived until she died in 1890. Her husband is still in Brecon, where he fell.

Charles Lumley VC was buried with full military honours in the churchyard of Brecon Cathedral. You will find his tomb quite easily if you look in the north east corner of the churchyard. Walk along the path that the children use and look up to the boundary wall.

Charles Lumley. Wounded at Sebastopol. Died in Brecon.

Words: Geoff Brookes

Images:

Brecon Cathedral – David Merrett (CC BY 2.0)

The tomb of Major Charles Henry Lumley VC in Brecon Cathedral cemetery – Bill Nicholls (CC BY 2.0)

The London Gazette citation – Source (OGL)

First published in Welsh Country Magazine in 2008