Long before short haul flights abroad were even thought of, we Brits liked to roll up our sleeves, turn up our trousers legs and even don our bathing suits as we holidayed at home. Numerous ‘hot spots’ around our coastline became ‘the places to see and be seen’ as our ancestors enjoyed the health benefits of the fresh air and the seaside location. In Wales, our long sandy beaches – often with a magnificent mountainous backdrop – became a magnet for those seeking rest and relaxation from everyday life in the towns and cities.

Feature image: Pier and Pavilion, Colwyn Bay, Wales, ca. 1890 – 1900 (Source)

A Picture of the Past

Before the nineteenth century, taking a holiday was a pastime only favoured by the wealthy upper classes. It was fashionable for young men – and some young women accompanied by a guardian or chaperone – to take off on a ‘Grand Tour’, visiting European cities to enjoy the sights and expand their knowledge of art, culture and traditions.

For those who preferred a change of scene on British soil, the Welsh equivalent of the English spa towns of Bath, Leamington and Harrogate could be found at Llandrindod Wells in Powys, attracting visitors to their pump rooms where cold water, mineral treatments and thermal baths were believed to improve wellbeing after illness. Trefriw in north Wales, with its close proximity to the coast, provided the prefect retreat for respite and recuperation and in 1874, when the current bath and pump house was built, Trefriw offered ‘hydrotherapy’ – bathing in, or drinking waters from a natural spring – to the public as a health restorative.

Sadly, the working classes were not quite so fortunate and were often only allowed one day off per week, which was intended for church going and time with their family. Before the introduction of the public Bank Holiday in 1871, workers could enjoy additional free time on religious occasions such as May Day, Easter or Christmas – the word ‘holiday’ deriving from the term holy day.

During the Industrial Revolution, the custom of holding a Wake, a religious festival held to commemorate the anniversary of a church or chapel, had been adapted into a regular summer break, especially for those working in the mill towns of northern England. Each area was appointed a particular Wakes Week in their annual calendar, during which all the cotton mills would close. Workers were given the time off, bunting went up, wells were dressed and flowers were gathered for decoration as fairs and celebrations were held in the towns.

But the growth of the railway network saw the working classes begin to use Wakes Week as an opportunity to travel affordably around Britain. With north Wales virtually on their doorstep, the Lancashire factory workers and those from the industrial cities of Liverpool, Manchester and Birmingham naturally migrated to the developing Welsh seaside resorts.

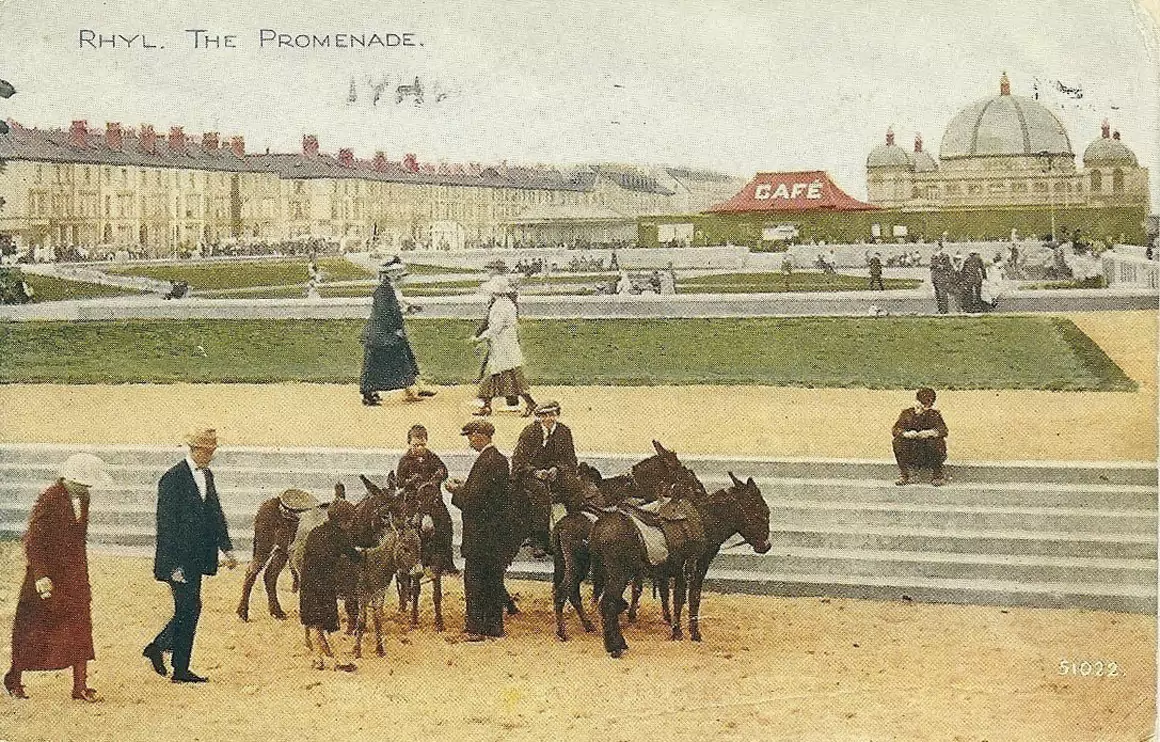

Families would alight from steam trains, buses and charabancs to enjoy a day trip or even a week by the sea in Rhyl, Llandudno and Colwyn Bay. Further down the coast, Barmouth, Pwllheli and Aberystwyth attracted holidaymakers eager for the freedom of the beachside location, a world away from their confined factory work and cramped conditions back home, whilst in the south, Tenby, with its cliff top walks and its Royal Victoria Pier, was popular with late nineteenth century travellers.

Depending on their finances, the working classes would stay in basic ‘digs’ or well regimented ‘bed and breakfast’ accommodation, presided over by landladies who instilled strict rules about the use of hot water and meal times, often expecting guests to vacate the premises each day by 9am and not return until 5pm.

A Window of Opportunity

Former Baptist preacher, Thomas Cook, believed that the lives of the working classes could be improved by guiding them away from alcohol through education. In 1841, he organised a special train to take a group of Leicester temperance supporters to a meeting in Loughborough. His venture proved an instant hit.

Former Baptist preacher, Thomas Cook, believed that the lives of the working classes could be improved by guiding them away from alcohol through education. In 1841, he organised a special train to take a group of Leicester temperance supporters to a meeting in Loughborough. His venture proved an instant hit.

By 1845, after numerous other planned excursions, he arranged trip to Liverpool which included low cost rail tickets, a handbook detailing the journey – the forerunner of today’s holiday brochure – and a supplementary charge for travelling by special steamer to north Wales. His trips to Wales, with its castles and beautiful scenery, were extremely well attended and he soon began to expand his itineraries to include locations further afield, even advertising his tours at the Great Exhibition of 1851.

Image: Thomas Cook (Source – CC BY-SA 3.0)

Making Memories…

For both the Victorians and later the Edwardians, certain requirements became synonymous with the perfect seaside holiday. A sandy beach with clean water to bathe in was paramount – inspiring the Blue Flag awards for cleanliness in later decades. One of the first bathing machines was introduced back in 1735 and the design gradually developed to enable maximum discretion whilst donning swimwear before entering the water.

Usually about six foot long and eight feet high, the Bathing Machine was like a sentry box on wheels which allowed bathers, especially women, to change from the restraints of their outer wear into a bathing suit in privacy. Some ‘machines’ were constructed with canvas walls whilst others were more robust wooden creations, either modestly decorated or emblazoned with brightly painted advertisements. All were wheeled into position by the water’s edge (either by man or horse power) allowing the bather to enter the surf via a set of steps whilst their clothes remained dry within a compartment inside. When their seaside experience was complete, the bather would return to the machine, dry off with the towels provided, change back into their street wear and alight from a door at the back of the contraption, their dignity intact!

Further diversions included a pier to promenade along, with the addition of a pavilion to showcase the latest entertainment, guaranteed to lure visitors for both matinee and evening performances. The ancient artistry of Punch and Judy puppetry amused the hoards of children who were mesmerised by the puppet characters, whilst donkey rides – introduced to the beaches of Britain in the 1890s – created the ultimate attraction for those with a love of animals. Llandudno remains the epitome of the nineteenth century elegant resort with its pastel coloured beachfront accommodation and its sweeping promenade. Richard Codman first set up his ‘Professor Codman’s Wooden Headed Follies’ show here in 1860; today, the Codman family Punch and Judy show continues to be as popular as it was over 150 years ago.

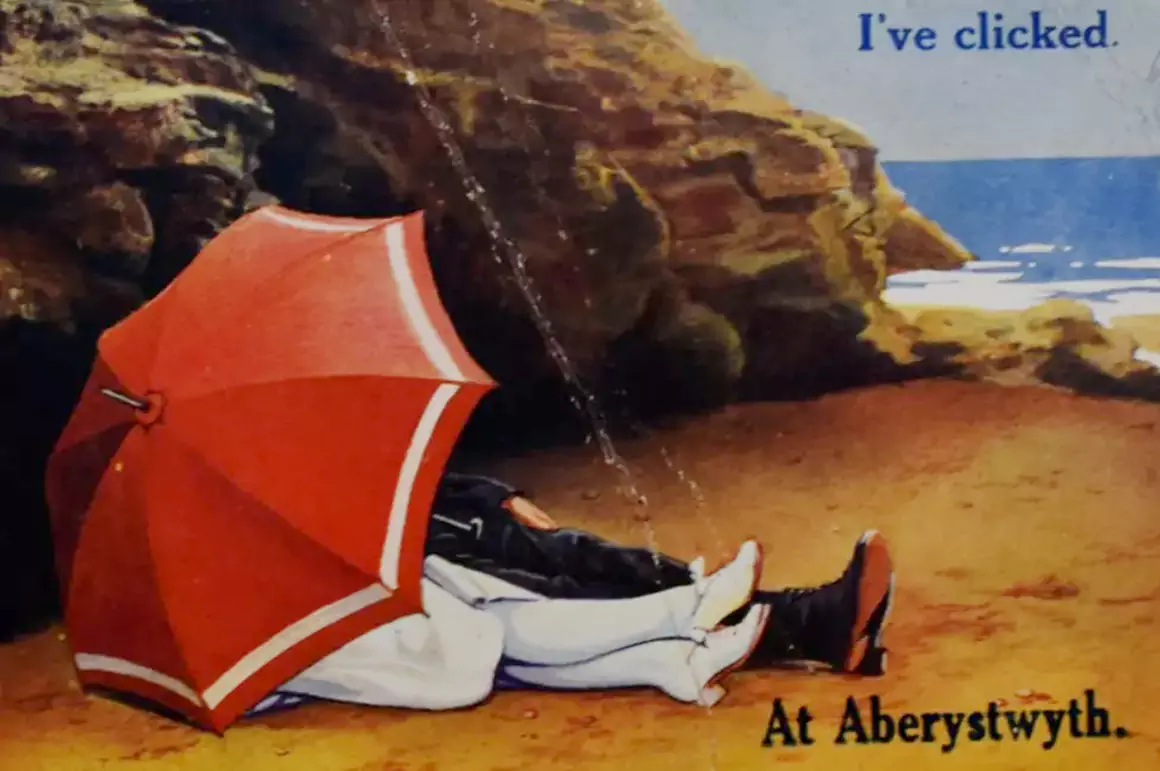

Tradition soon dictated that holidaymakers should take home a souvenir of their trip and manufacturers responded with a whole host of affordable seaside knick-knacks, shell-ware and ornaments decorated with mottos, or the gilded words ‘A present from…’ to provide a lasting reminder without breaking the bank. The 1870s saw the arrival of the postcard, enabling the traveller to write home and tell friends and family of their exploits whilst away. Initially, these cards were decorated with topographical scenes or historic landmarks, but later, cartoon style images appeared, embellished with saucy captions which appealed to the outgoing nature of the 1930s holiday maker. As a result, the souvenir industry became a staple trade in seaside resorts, providing seasonal jobs for many locals and becoming a vital part of the holiday culture for visitors.

Changing Times…

The war years inevitably limited travel and amenities and seaside towns concentrated more on defences from the enemy rather than deckchairs and donkeys. By the late 1940s, a new era dawned with the Golden Age of the holiday camp. In 1947, Billy Butlin took back his Llyn Peninsula camp from the Admiralty and Butlin’s Pwllheli with its famous Redcoat staff opened to the public, specialising in affordable accommodation, food and entertainment for all the family.

But even when Travel Agents appeared on our high streets giving the promise of ‘guaranteed’ sunshine in foreign climes, we continued to treasure the nostalgic memories of the British seaside holidays of our youth. In the twenty-first century, with the latest financial difficulties, we have seen a resurgence of holidaying at home. Wales offers some of the best beaches in Britain, so after one of our worst winters, let’s hope for a glorious holiday season so we can get out there and recreate those summers by the sea!

Words: Karen Foy

First published in Welsh Country Magazine May – June 2014