![]()

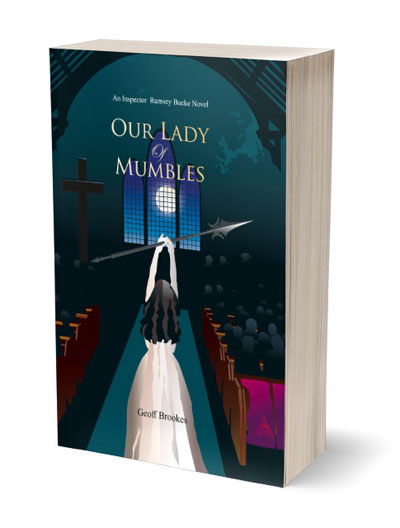

Our Lady of Mumbles is a new Rumsey Bucke novel, the second in the series. It is available on Geoff Brookes’ website for £11.

This price includes signing, a dedication if required and free delivery.

For more information or to purchase please visit: www.geoffbrookes.co.uk

Synopsis

It is the autumn of 1880, and Swansea is in the grip of a suicide cult. Only true believers will be saved in the imminent Apocalypse, once they have surrendered all they have to Our Lady of Mumbles and pledged their loyalty to the Spear of Jehovah.

Suddenly all normal values are distorted. Neither the old nor the young are safe. Young women are missing and bodies are found in the earthly paradise of the Penllergare Estate. There are symbols and portents everywhere, belief in reincarnation is common, angels are seen, and rats are swarm through the graveyard. Evil prospers,

Are these really the Last Days?

At this time, when happiness is denied and love is punished, Inspector Rumsey Bucke uncovers murder, suicide and dark family secrets. His own relationship with Constance is questioned by a reporter determined to ruin Bucke’s career and happiness.

Two resourceful women give Bucke the support and strength he needs to uncover a web of abuse and murder. But it is a dangerous time to be a woman, and as time runs out, he realises that those who he cares most about are in mortal danger. Can he save them before the Church of Our Lady of Mumbles eats itself?

Excerpt

Inspector Rumsey Bucke travelled on an early morning train to Cardiff to witness the executions. He did not want to go but his official duties demanded that he should. After all, he was the officer who had detained Nancy Peters and John Rowlands in Swansea after the murder and the Chief Constable wanted him to attend the inevitable consequence of their arrest.

He looked out of the window, seeing nothing, and considered the cruel details of the case. John Rowlands was a quiet, unassuming insurance clerk who had lodged with Nancy following the unexpected death of his widowed mother. An only son, he had lived at home for all of his forty five years, sheltered from so much of the life that most people experienced. Alone and lonely in his simple room, he had fallen in love with his landlady, Nancy Peters. She was a small, dark and very attractive grocer’s assistant, seventeen years younger than John, and trapped in an abusive relationship with her husband George, a violent man and a notorious drunk and petty criminal. She was more worldly than John and with her prompting, a relationship which began in stolen glances, soon blossomed into something more adult, bringing together two lonely and needy people.

Together, in the excitement and blindness of lovers, they plotted a unfeasible route to happiness, but the poison they administered to George in his tea did not work quickly enough for them, so emboldened by whisky, they pushed him downstairs and then beat him – eventually to death – with a poker. Nancy and John had then fled to Swansea where they took a room at the Gore House Hotel and went immediately to the Southern Seas Shipping Agency on Castle Street to book a passage to Australia in their own names, seemingly unaware until Dermot Murphy, the shipping agent, corrected them, that the route was served by no ships from Swansea. Bucke found them within an hour of receiving a telegraph message from Cardiff and the couple surrendered to him meekly.

Before their trial they both confessed separately to the murder in order to protect the other and Judge Frobisher, on the basis of those confessions freely offered, chose not to waste any court time determining precisely who had done what. They were both condemned to hanging and so now Rumsey Bucke had to watch them die.

At Cardiff Prison he made careful note of the arrangements and the specific duties of William Marwood the hangman and those of his assistant; he observed the two ropes hanging from a single beam above two tested traps and then stood to one side, with the scaffold looming above him, as the two separate processions brought Nancy and John to the gallows. She seemed insubstantial and bewildered; he was trying so hard to be brave but his eyes were dark holes of terror, in a face drained of all colour. Their arms were pinioned and on their heads were white hoods, sitting like caps, ready to be pulled down. Two chaplains were reading the service for the Burial of the Dead as the condemned couple mounted the steps and each was positioned below their noose. As the assistants quickly tied their legs together below the knees, John suddenly spoke.

‘It is a cold morning, Mrs Peters.’

‘I can’t stop shivering, Mr Rowlands. Tell me it will be quick. Please tell me.’

Their hoods were lowered and the ropes adjusted around their necks.

John Rowlands raised his voice. ‘I still love you, Nancy. I have no regrets.’

‘I love you too, John. But I am so cold.’

The two traps sprang open with a clatter and the couple dropped from view. From one of them, Bucke couldn’t tell which, came an audible snap. Then all was quiet. Justice had been served.

He thanked the governor of the prison for the permission he had granted to attend. There had not been an execution in Swansea for fourteen years and Captain Colquhoun wanted to make sure that someone in the town was acquainted with the necessary procedures, should the need arise.

Marwood was sitting at a desk in the office, eating a hearty breakfast. He smiled at Bucke as he mopped his eggs with a piece of bread. ‘I have never attended to business in Swansea, Inspector. I am told it would prove to be a pleasant location to visit.’

‘Long may that absence continue, Mr Marwood.’

He smiled. ‘I administer to the immutable consequence of human behaviour, Inspector, as defined by the law. Sooner or later I shall be coming to call, never fear. The residents of Swansea are no different from people anywhere. Neither are those of the fair town of Nottingham where I must go later this morning.’

As Bucke travelled home, disgusted by the tragedy he had witnessed, he stared out of the window once more, this time into the sunshine, though he still registered little of what he saw. His mind was suddenly undisciplined, chaotic, full of disparate images. His wife Julia and their children Anna and Charles, the family he had lost to illness over a year ago now, were always with him, but today they were joined in his imagination by Constance White as she now was, his friendship with her a guilt-tinged joy and quite suddenly the most important thing in his life. There were vivid and haphazard memories of his military service in India on the North-West Frontier, which were suddenly replaced by the single memory of his nausea brought on by the unpleasant smell of a man with a cut throat in a Swansea privy. Then there was the image of the last man he had seen hanged, suspended from a water pipe in the police cells, murdered by someone more cunning than the constables. He saw bodies pulled from the docks, vagabond children with wet noses and no shoes – all jumbled with scenes from his morning in Cardiff prison. Nancy, slight and dark, a victim on whom the sun shone for such a very brief moment, marched in solemn procession by impassive men to her death, with her unexpected lover and murderer, John Rowlands, a man possessed by such surprising passion. Life-changing, life-ending. Ordinary people betrayed and trapped by the law. We are all ordinary people, he thought. And we deserve so much better. He stared blankly but could find no peace.

Had a stranger entered that empty compartment they would have first noticed the neat hair and beard of a youthful forty year old and deep brown eyes that had carefully catalogued the darker experiences which had shaped him. The scar along his jaw line, his souvenir from the North West Frontier, was now barely noticeable except for those who inspected him more closely than good manners allowed. It was more easily hidden beneath the beard he carefully shaped in his one concession to vanity and which also served to distract attention from his incomplete earlobe, a legacy of the same blow.

He left the train at High Street Station in Swansea and crossed the road to Tontine Street and the police station. It was a solid, reliable-looking building of attractive brick, with three curved steps leading up to a pair of fine mahogany doors with stained glass inserts. He always found it a comforting and re-assuring place, an oasis in the frequently chaotic world which surrounded it. The one unfortunate feature of the building, in his eyes, was the windows. Tall, arched, smart and the perfect target for the stone-throwing disgruntled. Today they were happily intact. He walked through the door, triggering the bell on the frame. He immediately smelt the polish, the daily legacy of three devoted and proud early-morning cleaners. Everything was clean, calm and ordered, the loudly ticking station clock marking out its measured tread. And it had ticked just so, all morning, whilst in Cardiff two ordinary people who loved each other had been executed.

‘Good afternoon, Inspector,’ said Sergeant Ball, who was standing, as always, behind the counter, ready to receive visitors anxious to be comforted by his generous smile and his avuncular manner. ‘A grim business it must have been, I am sure.’

‘Oh yes, Stanley. Most unpleasant.’

‘Wouldn’t like to see a woman hanged. Did Marwood do his job properly? She didn’t suffer, did she? They say he can make mistakes.’

‘Thankfully it was efficiently done.’ Bucke shook his head slightly, remembering.

‘At least that is some comfort. Her husband was a proper villain by all accounts, Inspector. Asking for it, I am told. My cousin is a constable in Cardiff, see. Glad to see the bugger gone.’

‘But at a terrible price, Stan. And how are things here today?’ Bucke looked around at the empty foyer.

Ball opened the ledger he kept on the counter and indicated that little had been added today. He turned to look at the clock. ‘Calm all over today. You should go to Cardiff more often. There was a bit of a problem out at Glebe Colliery in Loughor last night. Someone has been damaging locks and chains, trying to get inside, they say. Goodness knows why.’

‘Is it ours? Or is it one for Carmarthen?’ asked Bucke hopefully.

‘Ours, I regret. I have checked. The pit entrance is on our side of the river. I said you might go over there tomorrow but I do not believe that it is necessary. The local bobbies can deal with that, Inspector. Just youngsters, I’ll be bound. Or tinkers. ’

Bucke sighed. Those local constables, Stephens and Dennis, never filled him with confidence. ‘Anything else, Stan?’

‘Only that the Chief Constable called in, Inspector.’

‘I am glad of it. He said he was hoping to call this morning.’

‘If I might say, sir, it is good to see The Chief Constable out and about.’

‘Yes it is, Stan. A welcome improvement in our arrangements.’

The new Chief Constable, Captain Colquhoun, had replaced the disgraced Chief Constable Allison and made an immediate impact. He stayed as close to his constables as he could, showing a proper concern for their welfare. He was eager to modernise the force and immediately upon his appointment replaced their old wooden rattles, unreliable and unwieldy, with loud whistles. Of course, the constables were immediately won over – whistles would leave them able to signal for help whilst keeping both hands free with which they could defend themselves. Colquhoun and Bucke had quickly become close colleagues, a relationship based upon mutual respect and one which made the Inspector feel much less isolated than he had previously.

‘He used your office to have a word with Constable Plumley, Inspector.’

‘I hope he has more success than I have had to date.’

Constable Herbert Plumley had been much troubled recently. He had never possessed the sunniest of dispositions, as Sergeant Ball frequently observed, but following the incident on the Strand during the recent failed assassination attempt, where he had confronted a group of drunk Italian seamen surrounding a disembowelled corpse and effected a swift and entirely inaccurate arrest, he had become bitter and morose. His new-found devotion to the church had done little to lift his mood. He was thirty two years old and many men of his age affected an interest in the church as the most acceptable way to advertise themselves in the marriage market and thus meet demure young ladies, but as far as Bucke was concerned, Plumley seemed only to have sought out God in order to immerse himself in retribution. There had been an incident the previous week when he had detained Oonagh O’Grady’s boy Finn, who had stolen some carrots in the market and, with his police staff, had applied an extended punishment which was out of all proportion to the offence. It had taken a long and uncomfortable meeting with the family in their home on Jockey Street for Inspector Bucke, using all his diplomatic skills, to prevent the emergence of vendetta against Plumley by the Irish community as a whole.

‘I am not sure that Captain Colquhoun found it an easy meeting,’ said Sergeant Ball. ‘Our Herbert doesn’t say much these days. But I agreed that we would assign him to different duties. I’ve got him over in Llansamlet now. Quiet over there at the moment.’

‘And are there any guests downstairs today, Stanley?’

‘No, Inspector. Had a drunk French sailor in overnight, but when he had sobered up he started singing so I kicked him out. Cheeky bugger wanted breakfast. Thought we were a hotel. We were close to bringing someone else in this morning. Winnie the Washer was preaching in the market and telling all the stall holders they were sinners. Well, we know that, don’t we? But they didn’t like it, said it was keeping customers away. So I sent Constable Bingham down there to move her on but she had disappeared.’

‘In which case, in view of the unaccustomed tranquillity here, I shall walk down to the Town Hall and appraise Captain Colquhoun of my morning’s experiences. Fear not, I will report to you immediately should I see any signs of religious mania, Sergeant Ball.’

‘You make sure you do, Inspector,’ nodded the sergeant.

Inspector Bucke picked his way carefully between the dung and the debris on High Street on his way to the Chief Constable’s office in the Town Hall, close to the South Dock. In front of him on Castle Street he could see that a small crowd had formed, with Constable Bingham hovering ineffectually around the edge.

In the middle of the street and clearly unwell, Winnie the Washer stood ranting. It seemed that she had beaten her tambourine so viciously that its skin was flailing about in tatters as she banged it against her head. It rattled comically, contrasting with the blazing insanity in her eyes. ‘I have looked into the eye of God! He will never forgive me! I have looked at an empty socket in an empty skull!’

‘Give us rest from all this, Winnie,’ someone shouted. ‘We have heard it before.’

‘Did you not know? I am Jezebel. I am the wife of Ahab. Naboth shall be stoned to death and I shall be eaten by dogs!’

‘I will go and fetch a couple then,’ said a voice in the crowd to general amusement. ‘Put us all out of our misery!’

‘There shall be an altar of Baal in my dwelling place!’ She threw out her arms and raised her head to the grey clouds, then slumped to the ground, her face wet with tears. The small crowd of angry shopkeepers jeered as Bucke slipped between them and bent down and gently took the broken tambourine from her. He placed her hands in his.

A voice shouted from the crowd. ‘Shut her up, for God’s sake Ramsey!’

Someone else laughed.

‘It is for God’s mercy that I am here,’ she sobbed.

‘Be calm, Winnie. Do not trouble yourself so. Here, let Constable Bingham care for you. He will take you to where you can rest.’

She looked at him imploringly, with tears streaming from her eyes. ‘You must believe me, sir. I am Jezebel. I will be trampled by horses for what I have done. I know I will be eaten by dogs. I didn’t want to do it. He made me do it, sir and now I am damned.’

Bucke rubbed her hands gently. They were scabbed and scarred. Blood was seeping from cracked wounds. He spoke to her gently. ‘Your hands are so rough, Winnie. The hands of a navvy.’ He smiled at her. ‘You haven’t been working down the pit again, have you?’ He moved one of his hands and touched the side of her face. ‘Go with the constable, Winnie. Please. He is a good man and he will not harm you, I promise.’ He helped her to her feet and she submitted herself quietly to Constable Bingham who led her away. The small crowd dispersed, their entertainment concluded.

No one could be sure who she was, for Swansea provided easy anonymity for those who lived in its slums. They knew Winnie merely as a washerwoman and occasional petty thief, who half-heartedly scrubbed the clothes of those no better off than herself, in a tub of water so filthy it was impossible to see how anything could ever be cleaned. People had stopped using her, seeing a connection between her and a short but vicious outbreak of cholera amongst her customers, their deaths, according to Baglow, a reporter for the Cambrian newspaper, ‘bred in the squalor of a filthy alley.’ Within days she was destitute and her mud-floored room in Regent’s Court abandoned. She had re-appeared with a tambourine, singing hymns and occasionally raving outside the castle or outside St Mary’s Church, abused by the people and ignored by the pigeons.

Bucke watched her stumble slowly up High street with the constable and wondered what would become of her. Like Plumley, her religion seemed to be bringing her no comfort. He turned and headed towards Wind Street and down to the Town Hall.

Our Lady of Mumbles is published by Llyfrau Cambria Books, Wales and available in bookshops or on-line and at www.geoffbrookes.co.uk.

Also available, Stories in Stone by Geoff Brookes