![]()

It is such a distinctive church, and can be seen for miles, standing tall and pale on the coastal plain. It has an elegant limestone steeple, in keeping with its beautiful interior. St Margaret’s Church in Bodelwyddan, ‘The Marble Church’, is an impressive place. It has inside many different types of marble, including beautiful Belgian red marble in its pillars. The style and the decoration are enough to draw the visitor, but it has other interests too.

The church is surrounded by a small neat cemetery, in the north east section there is the grave of Elizabeth Jones, who was the mother of Stanley, the explorer.

Then examine the south side, you will find a host of military graves. There are 34 British graves and 83 graves of Canadian military personnel who had been stationed at the nearby military camp at Kinmel Park, outside Abergele. They have a memorial cross of red sandstone and their graves are grouped around it.

Our military heritage spreads far and wide, encompassing the legacy of empire and commonwealth. We must never forget that people from across the world have fought and died for us, and some of them rest with us still, and here in Bodelwyddan it is the children of Canadian mothers. As they have rested, rumours have grown about these Canadian graves, rumours of riot and summary execution, in the aftermath of war in March 1919. But the question has always been, why did these survivors of the Great War die in north Wales?

The Kinmel Camp near Abergele was built in 1914 as a training camp for the north Wales battalions, and when the war ended it became a transit camp – a base for soldiers from across the Empire, waiting to go home. The 9th Canadian General Hospital was there too, it contained, in huts and under canvas, 1290 beds; it was a busy place.

In the late winter of 1919 the camp was dirty and overcrowded, the Canadian soldiers were on half rations, they hadn’t been paid, 42 men lived in huts meant for 30, there was no coal for the stoves, and there was a shortage of bedding which meant they took it in turns to sleep on the floor. March can be cold in north Wales.

They just wanted to be home and four months after the end of the war, very little progress was being made. There were over 15,000 of them and as far as they were concerned their military service was over.

Repeatedly they were processed and given a place on a ship, which then didn’t turn up. Whilst they waited they continued to live under military discipline, with drill, parades, and forced marches. Local tradesmen, who set up stores in adjacent shacks in what they called ‘Tin Town’, were felt to be profiteering, overcharging men who had little money in the first place.

There are always frustrations too, when you think you are in a queue and yet others seem to be dealt with first. Sometimes, newly arrived troops appeared to be sent home before longer term residents.

Certainly the camp was not a cheery place to be, and things at home weren’t ideal either, and the Canadians were not sure what they would find when they returned. Unemployment in Canada was widespread, the economy was crippled by war debt, industrial unrest was growing, and the Government was calling in the troops, yet the soldiers themselves had started to fraternize with striking workers. Communists were a hidden sinister threat, blamed for the unrest. It speaks of a society in considerable unrest, uneasy in the aftermath of the Russian Revolution. This tension reached out across the Atlantic to north Wales. Overseas workers, generally Russian immigrants, were being deported to provide work for returning soldiers. But it offered little comfort, for many of them were of Russian descent themselves.

Strikes at home had held up the repatriation ships, promises that those who had enlisted first and married men, would be sent home first were not being fulfilled. They were probably being sent home by unit, rather than by date of enlistment. But it was certainly a big issue and the commander of the camp, Colonel Colquhoun, sent Colonel Thackrey to London to discuss the problem. Meanwhile, the camp believed with absolute certainty that a troop ship intended for them had been diverted to Russia to carry grain.

Not only that, but Kinmel Park Camp was also a dangerous place to be, soldiers were dying in the flu epidemic, that had reached the camp in October 1918 and which would eventually account for the vast majority of the casualties now buried in the cemetery.

The 1918 flu pandemic (often called ‘the Spanish flu’) spread to nearly every part of the world. Unusually, most of its victims were healthy young adults, those who had survived the Great War.

The epidemic began in March 1918 and went on to kill anywhere between 2% to 5% of the human population. People could be apparently well, then suddenly overwhelmed by symptoms, and then dead the following day. The flu provoked huge fear right across the world and the conditions in a place like Kinmel were ideal for the spread of the virus.

February 1919 was a particularly bad month, as the dates on the headstones testify; Kinmel Park Camp was clearly somewhere you would not wish to be.

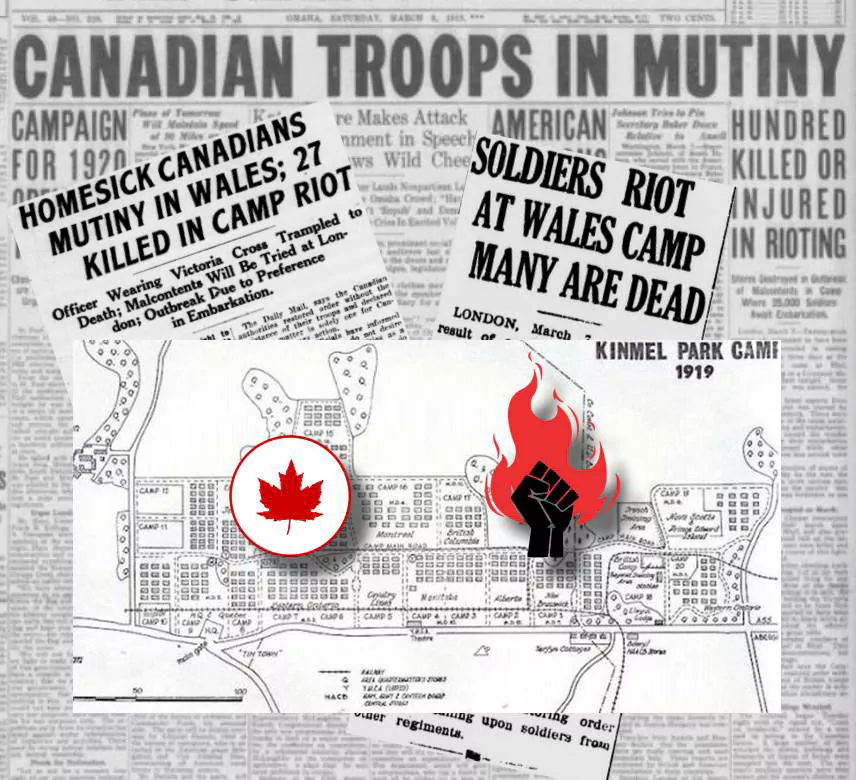

It was inevitable that frustrations would eventually boil over and the riot started on Tuesday 4th March 1919. A committee was formed with the intention of starting a mutiny that they hoped would spread through all the estimated 15,000 men. The leader of the action was identified as William W. Tarasevich of the Canadian Railway Troops. They began by ransacking the canteen and soon gangs were roaming around the camp, looking for other ways of expressing their anger.

They broke into the rooms of girls who worked at the camp, but only to steal overalls. Then they moved on to Tin Town and smashed it up.

Colonel Colquhoun acted swiftly, he ordered all remaining beer to be poured away and all ammunition removed. However, there is a suggestion that the rioters looted a brewer’s dray on Wednesday morning when it turned up at the camp. The Times said that this “may account for the horrible turn of events in the course of the afternoon.”

Colquhoun tried his best to calm events, by moving about through the camp and speaking to the men, in so doing, his presence managed to control the spread of the disorder.

However, on Wednesday afternoon there was a confrontation between the rioters and those who had remained loyal, some soldiers on both sides had retained firearms and ammunition, and perhaps it was inevitable that they would be used. A shot was fired and Gunner Jack Hickman took a bullet to the heart, as he sat in his hut writing a letter home. Another four were killed in the hand to hand fighting that followed, including Tarasevich; the riot was over.

Tarasevich was the perfect scapegoat, the rioters had already been described as ‘not true Canadians but men with Russian blood’ and his death was especially convenient, because everyone could blame a dead man, with a Russian name and then move on.

Official reports might blame Russian Communists for the riot, the Times says:

“In the camp itself there is a strong belief that Bolshevism tried to raise its head and was scotched.” but the reporter himself was more circumspect.

“To what extent the use of the red flag – it was a piece of bunting that had flown at a canteen – signified a political impulse behind this unhappy business; it is difficult on present information to say with any confidence.”

What we do know is that those who died in the riot received a military funeral in St. Margaret’s, with six pall bearers, a firing party of 12 men, 24 mourners, and a bugler. Hickman was taken home for burial, but the other four are there.

- 1. Canadian War Memorial

- 2. War Graves

Tarasevich, 30 years old, bayoneted in the abdomen.

Corporal Joseph Young, 36, an Infantryman in the Manitoba Regiment, who died in hospital after being hacked in the face with a bayonet.

Gunner William Haney, 22, of the Canadian Artillery, who was shot in the face.

Private David Gillan, also 22, of the Nova Scotia Regiment, was shot in the back of the neck. Gillan’s memorial is a larger private headstone. It reads, ‘Killed at Kinmel Park on March 5, defending the honor of his country.’

Whilst it is believed that the first three were part of the riot, there was no distinction in death. Who can tell what small acts of heroism they had performed during their service in Europe? So they are rightly buried together.

The unrest faded, General Sir Richard Turner VC travelled from London and re-assured the troops that four transports to Canada would arrive as soon as possible. He acknowledged that there had been difficulties in shipping in February, but he hoped and promised that things would improve.

Of course there had to be Court Martials, and soldiers were sentenced and imprisoned, but they were soon quietly sent home along with their comrades.

There was, naturally, some excitement in the press which was probably the origin of all the myths about the riot that persist to this day. The riot was carefully planned by Russian Communists, desperate to incite revolution. There have been stories of 12 officers being killed, of Irish Guards being sent in to quell the riots, of summary executions by firing squad, heard clearly by frightened locals, and of 21 dead soldiers buried secretly in unmarked graves… But there is no evidence at all for any of this, The Canadian National Defence Headquarters denied it all and the Military Court of Inquiry was quite clear in its careful narrative of these sad events.

So does St. Margaret’s Church hold a terrible and sinister secret?

Probably not.

Certainly a tension exists between the official version and an alternative oral tradition. But it is in the nature of conspiracy theories, that they persist, after all they can be attractive, they can give a seductive order to otherwise random events. Life however is generally far too untidy, there were no mass executions in Kinmel Park, there was no revolutionary uprising that was brutally suppressed. Just a sudden eruption amongst men desperate to get home, men whose sensibilities had been coarsened by their experiences in the trenches, for whom life had a disturbing cheapness.

The truth is probably quite straightforward.

A frustrated, frightened group of soldiers, a long way from home, facing a silent invisible killer in the shape of influenza, living in dreadful conditions, exploited, cold and hungry, were incited to riot. For a brief moment disorder ruled and then the madness passed.

On Joseph Young’s gravestone is the message: ‘Sometime, sometime we’ll understand.’

I hope that we do.

Perhaps in the end we need to look no further than the marble cross right at the end of the first row of graves.

‘In memory of Nursing Sister Rebecca Macintosh, died at Kinmel Park 7 March 1919. Aged 26 years.’

So whilst the riot was going on, a member of the Canadian Medical corps was dying of flu in the hospital. That was the true killer in the camp. The soldiers had all been heroes, like all the ordinary men who fought in the war. Then they had fought each other in their fear and their frustration.

Those 83 graves in Bodelwyddan are not there because of an act of suppression and brutality. They are a small part of a global catastrophe.

Words: Geoff Brookes

Feature image: St Margarets Church, ‘The Marble Church’, Bodelwyddan © Jeff Buck (cc-by-sa/2.0)

Image 1: © Philip Halling (cc-by-sa/2.0)

Image 2: © David Dixon (cc-by-sa/2.0)

Image 3: © Gary Rogers (cc-by-sa/2.0)

First published in Welsh Country Magazine May-Jun 2010