![]()

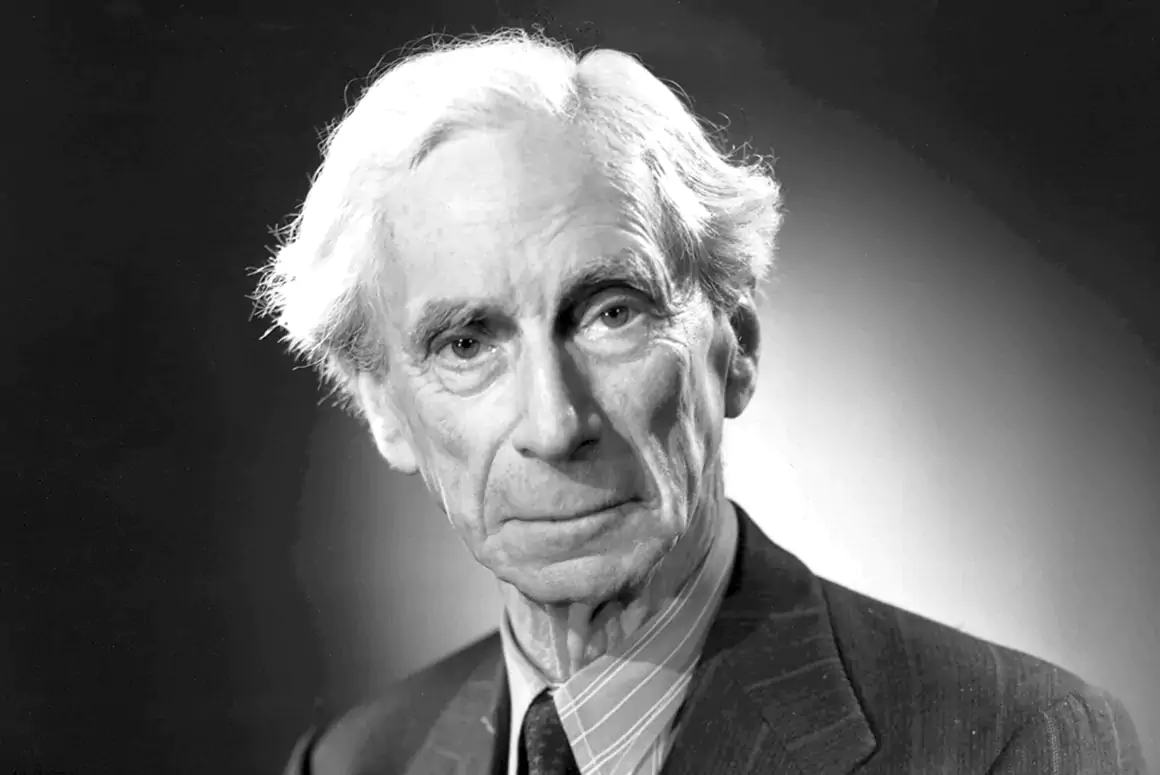

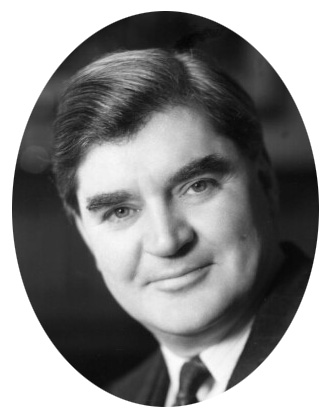

When he passed away on 6th July 1960, there was ‘an outpouring of national mourning’. Over 40 years later, in 2004, he was voted top of the poll in a clarion call of 100 Welsh Heroes, his role in the founding of our Welfare State, and our NHS, not forgotten. We’re talking Aneurin (or ‘Nye’) Bevan.

A British Labour politician to be, and a conviction politician to boot, Bevan was a working class lad, one of ten children of a miner in Tredegar, once in Monmouthshire, now Blaenau Gwent. Nye, as we affectionately know him, started down the mines aged just 13 on leaving school. Tredegar would provide more than solid working class roots. The Tredegar Medical Aid Society provided a template for Bevan’s future model for the NHS.

Bevan showed that proclivity for organising and campaigning early, as he was chairman of a miner’s lodge (the Tredegar Lodge of the South Wales Miners’ Federation) aged only 19. He got actively involved in trade unionism in the South Wales coalfield, won a scholarship to study in London, became convinced that socialism was the way forward, and led local miners during the 1926 General Strike.

Entry into national politics came quickly, as Bevan won the Ebbw Vale seat at the May 1929 General Election for the I.L.P. (Independent Labour Party), a seat he held for over 30 years until his death. Come 1931, he was a member of the more moderate Labour Party and was re-elected unopposed at the October Election, which showed the solid backing Bevan received from his constituents. Bevan married in 1934 to the Scottish politician Jennie Lee, another miner’s child and left-wing firebrand, who it is said was more left-wing than Nye.

There seem to be few genuine orators in British politics today, but Nye was certainly one, although he had to overcome a speech impediment along the way. He could be irreverent, tempestuous and caustic, but also brilliant. Among his early targets were Winston Churchill and David Lloyd George (Tory and Liberal respectively), Ramsay MacDonald and Margaret Bondfield (both from his own Labour Party). At least he was fair in criticising all the major parties!

It’s a bit of wartime mythology that everyone was four-square behind Churchill. Bevan certainly wasn’t and has been described as a ‘one-man opposition’. This may seem surprising to us now, but, at the time, there was much Nye was unhappy about, such as the heavy censorship and powers to intern citizens. He also wanted to see bold action taken to turn the tide, including the opening of a Second Front to help the Russians. In one of his most vitriolic and passionate outbursts he criticised a PM who ‘wins debate after debate and loses battle after battle’. Later, Churchill would denounce Bevan as a ‘squalid nuisance’. The two men were not exactly best mates.

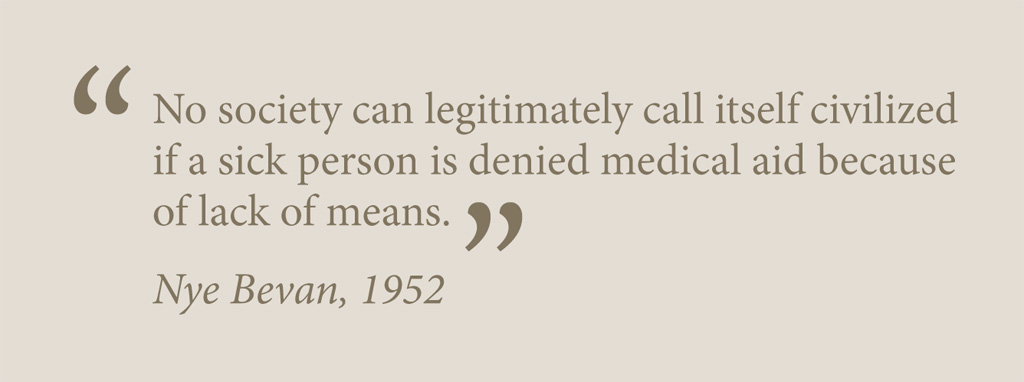

Nye perhaps had the last laugh, as Churchill won the war but lost the peace, being defeated in the General Election of July 1945, as thoughts turned to post-war reconstruction under a Labour Government headed by Clement Attlee. Bevan was appointed Minister of Health, and, in that capacity, introduced the revolutionary NHS in 1948. Given how the NHS is still revered, it’s easy to understand why Nye still has something of a cult-following. “Our hospital organisation has grown up with no plan, with no system; it is unevenly distributed over the country… I would rather be kept alive in the efficient if cold altruism of a large hospital than expire in a gush of warm sympathy in a small one.” (30th April 1946, House of Commons). On 5th July 1948 the Government duly took over responsibility for all medical services, with free diagnoses and treatment. The principle (which still holds) of healthcare, free at the point of delivery, and based on need, not wealth, was established.

In 1951, Bevan became Minister of Labour, but resigned after a few months in protest at health charges (dental care and specs) proposed in the Budget: a conviction politician again. He could not tolerate cuts in spending on social services. It was from this point that Nye had an ‘ism’ named after him, ‘Bevanism’, his attempt to move the Labour Party to a more Socialist stance. It was a one-man ‘left-wing nagging movement’ (less reformist, more socialist). It’s interesting, but Bevan foreshadowed some of the debate that would occur within the Labour Party in the future about exactly what its philosophy should be. Bevan was its leftish mouthpiece of the time.

Bevan was at the epicentre of the storm, at the heart of bitter and prolonged disputes with his leadership about the Labour Party’s direction. The party itself would also find itself out of office. Having won the February 1950 Election by a narrow majority of five seats, Labour called a snap election for October 1951 in the hope of getting a bigger majority, only to end up back in opposition, as Bevan’s nemesis, Churchill, returned as PM. The sting was taken out of Labour’s in-fighting when Bevan became Shadow Foreign Secretary: perhaps there was also a feeling that the common enemy was the new Conservative Government. “Winston Churchill … does not like the language of the 20th century; he talks the language of the 18th century. He is still fighting Blenheim all over again. His only answer to a difficult diplomatic situation is to send a gunboat.” (2nd October 1951, Scarborough).

‘Bevanism’ lost its eponymous figurehead in 1957, when Nye Bevan opposed ‘a one-sided renunciation of the hydrogen bomb by Britain’. “You will send a foreign secretary, whoever he may be, naked into the conference chamber.” (2nd October 1957, Brighton). You couldn’t really have Bevanism without Bevan. This all played out at that year’s Brighton Conference, which all sounds very Harold Wilson, or at least Mike Yarwood playing Harold Wilson.

Bevan became Labour’s Deputy Leader in 1959, a position he held until his death. Having been defeated in a bitter contest by right-wing reformer Hugh Gaitskell for the party leadership (1955), Nye managed to cooperate with him thereafter, although some of the leader’s views would have been anathema to Bevan, including a desire to remove Clause IV of the Labour Constitution (that one committing Labour to nationalisation which Tony Blair finally ditched). Gaitskell had his own ‘ism’ (‘Gaitskellism’) although it was neither as popular, nor as easy to pronounce, as Bevanism.

It’s fair to say that Bevan was the most publicised Labour politician of his time. He was instantly recognisable in word and appearance, an old-fashioned politician in many ways who brought a South Walian radical fervour to the benches and a restlessness that was both intellectual and fertile. In his own words he was a ‘projectile launched from the Welsh Valleys’, a voice for the underdog. He died of cancer on 6th July 1960, aged 62, his ashes scattered on the hills above Tredegar.