Although I am both an English teacher and a writer, I always seemed to have an uneasy relationship with words. This is not to say that I disliked them, or they me; in fact, I love words and welcomed them fully into my life from an early age, making sure that I was up long before the rest of the house to read the freshly-delivered newspaper, perching on the bottom stairs and reading it cover-to-cover. Despite this, the friendship in those early days was never as close as it would one day become, for a number of reasons.

To begin with, I found that they often had the capacity to make me feel like a pauper in the street, standing nose to the glass of the jeweller’s window and gawking at all the pretty things never meant for me. In books and magazines, I would occasionally stumble across such beautiful, shiny linguistic trinkets as mellifluous, loquacious and obdurate, all lovely things that felt wonderful when swilled around in my mouth, but which I’d never have occasion to use, always keeping them tantalisingly out of my reach.

Time often conjugates such lofty thoughts, transforming them into something of an earthier variety, and so I, like the vast majority of children, spent quite some time flirting with danger on the wrong side of the grammatical tracks. Those earlier gorgeous lexical specimens were soon cast aside in favour of a pocketful of the four-letter variety. These were a different matter altogether. That grown-up sense of confidence when casually flicking a string of expletives at a friend brought a frisson of excitement and a dangerous pulse of adrenaline only felt when sailing so close to the wind, particularly if a brief miscalculation and ensuing slip-up at home was the catalyst of one of those wait-until-your-father-gets-home moments.

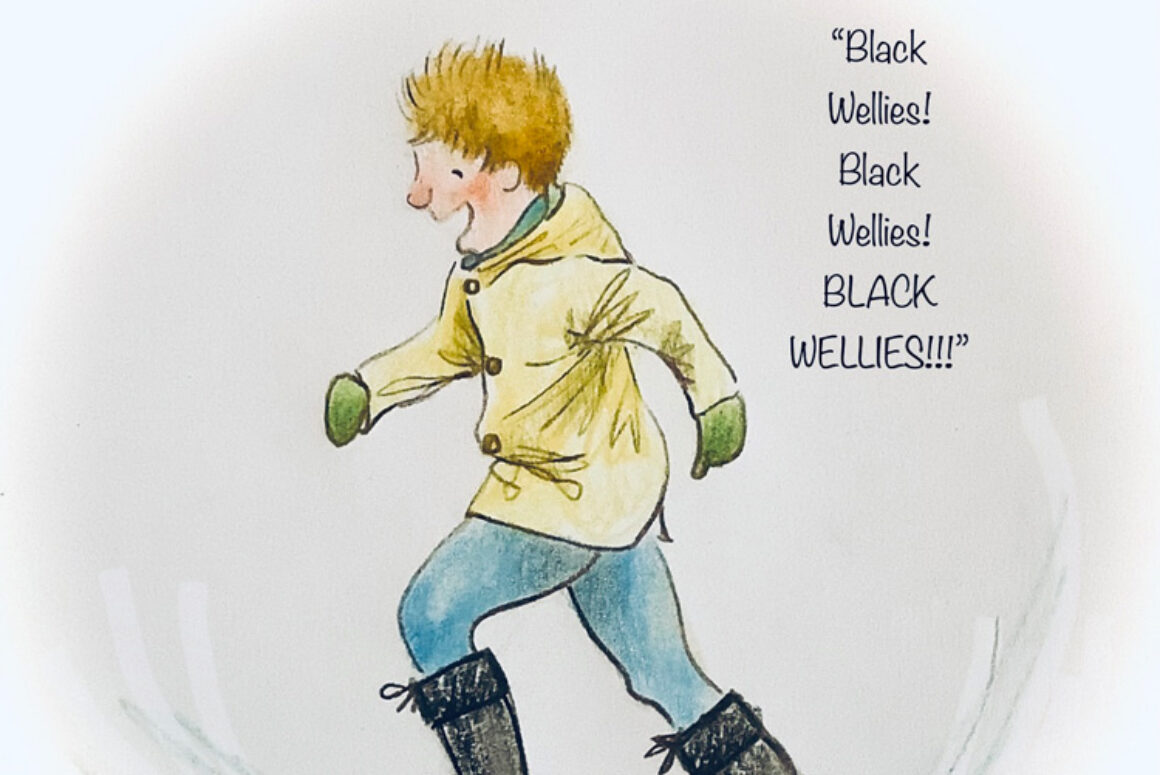

I’ve never forgotten a colleague of mine, many years ago, whose young grandson had fallen under the hypnotic influence of curse words having stumbled across one or two by accident then refusing to let them go, brandishing them proudly like a prized toy. Encouragement, bribery, pleas, threats – none of them succeeded in convincing our young protagonist to surrender his newfound vocabulary until, in a stroke of genius, my colleague’s husband took the boy to one side and, in a conspiratorial whisper, murmured: “Do you know the one thing you should never, ever say – the worst thing you could possibly call out?” Ladling on the melodrama, he put an arm around the boy’s shoulders and drew him closer, glancing furtively both left and right before muttering: “It’s really, really, really rude to say…’black wellies.’”

“Black wellies?”

“Ssssssh!” More furtive glances. “You should never say those words, especially not to nan!”

“Black wellies? Black wellies. BLACK WELLIES! BLACKWELLIES BLACKWELLIESBLACKWELLIESBLACKWELLIES BLACKWELLIES!”

With an impish grin, our would-be hooligan marched through the house, upstairs and down, proudly announcing “BLACK WELLIES!!!!” to a chorus of faux theatrical gasps, exaggerated expressions of shock and the dramatic clapping of hands over mouths. Sometimes, a white lie, even if it is a lie about wellies, can make all the difference.

Now that I’m on the subject of white lies, it was a little fib that really switched me on to the power of language during the first year of secondary school, and altered the nature of my relationship with words forever. Whilst competing a story-writing homework task for my English teacher, I embellished it with the simile: @he was tossed about like flotsam in a jet stream’, a simile of which I was very proud, but also a simile which I had lifted directly from an issue of COMBAT magazine, and a story following the perilous mission of a stranded submariner during World War Two. For weeks after, I basked in the accolades and positive feedback from my English teacher, the blue star sticker in my book noting the fact that I had cracked it – I was now conqueror of the English language.

Later life has taught me that it is a simple, two-letter slide from ‘conqueror’ to ‘conquered’, and that trying to be master of the English language is something akin to teaching an eel to ride a bicycle, particularly as it is so fickle, and will happily abandon us, leaving us tongue-tied at any given opportunity.

The early years of parenthood were one prime example, particularly the bedtime story at the end of a long working day. Invariably, we would begin following the adventures of some sweet character but, as the story wore on, the soporific effect of those words, spoken so gently, would weigh heavily upon my eyelids as they lowered…

and lowered…

and lowered further still until, half asleep, the correct words would suddenly fly south for the winter, leaving me with a string of garbled, incoherent stragglers and an admonishing wake-up call from my daughter Elle: “Daddy! That’s not how it’s supposed to go!”

These days, I find that my words no longer even wait until I’m tired before brazenly abandoning me completely, correct terminology and accurate terms now replaced by a stream of thingies, oojimaflips and whatchamacallums.

As I get older, Rachel demands to know that I’m fishing safely, no matter what my protestations may be, so I now find myself arriving at what can perhaps be considered my final linguistic indignity. An app on my phone will now generate a short string of three words that I text to Rachel upon my arrival at my chosen fishing spot, those three words enabling anyone to locate me should I not arrive home safely at the end of the night. I thought about kicking up a fuss about all this before realising that I was simply being obdurate, and knowing full well that I’m nowhere near loquacious enough to talk my way around the mellifluous, yet firm, tones of my good lady anyway.