![]()

I‘m sure most readers (like me) were taught in Junior School how Britain set a wonderful example to the rest of the world in the 1800s by abolishing the slave trade, then slavery itself, forgetting of course that we helped start it! Most people will have heard about the two main Acts of Parliament, firstly to abolish the trade, passed in 1807, and then slavery itself in 1833. But, how few have also heard of the subsequent Slave Compensation Acts, which compensated, not the poor slaves, but their former owners, who claimed to be in dire financial straits as a result of losing their ‘property’?

Between 1834 and 1845 the Slave Compensation Commission paid out around £20 million (multiply by 120 to convert to today’s values), to around 40,000 slave-owners. How was the money raised? – from a loan of £15m and £5m in taxes. That £15m was worth £1.43 billion in 2020 based on inflation, or £76.5 billion if you base it on the share of the country’s Gross Domestic Product (GDP or income), as many historians consider more realistic. When was it finally paid off? – as late as 2015. Note also, the tax part came from duties, revenue on goods, alcohol, etc, not direct taxation such as income tax, so it was the poor people in this country who ended up paying disproportionately more of their income to ex slave-owners, including over 100 sitting MPs, so there’s nothing new in political sleaze scandals!

A website called ‘Legacies of British Slavery’ (ucl.ac.uk/lbs/), records all the money paid out if you want to know more. It lists all claimants living in Britain at that time, so you can search the records by name and location. I decided to look at local connections in the area of the former county of Monmouthshire (not the present ‘slimmed down’ council area). Fourteen people are listed, but only half were successful in their claims.

This is the story of possibly the most controversial of these, especially now when we are rightly reminded that ‘Black Lives Matter‘.

William Wells came from a wealthy Cardiff family and emigrated to St Kitts, in the Caribbean, first as a slave trader then a plantation owner, sometime in the 18th Century. When William’s wife died, he began fathering children by his black female slaves – and produced at least six offspring, all by different women! Nathaniel, born in 1779, was the eldest of these. Although relationships with slaves were not uncommon at the time, Wells senior differed from the majority by looking after both the children and their mothers, giving them their freedom and money to live on – including Nathaniel’s mother, Juggy. At the tender age of ten Nathaniel was sent to London to be educated and stayed on in Britain after his father died in 1794, inheriting the bulk of his estate – three plantations, 146 slaves, plus £120,000, whilst still only fifteen.

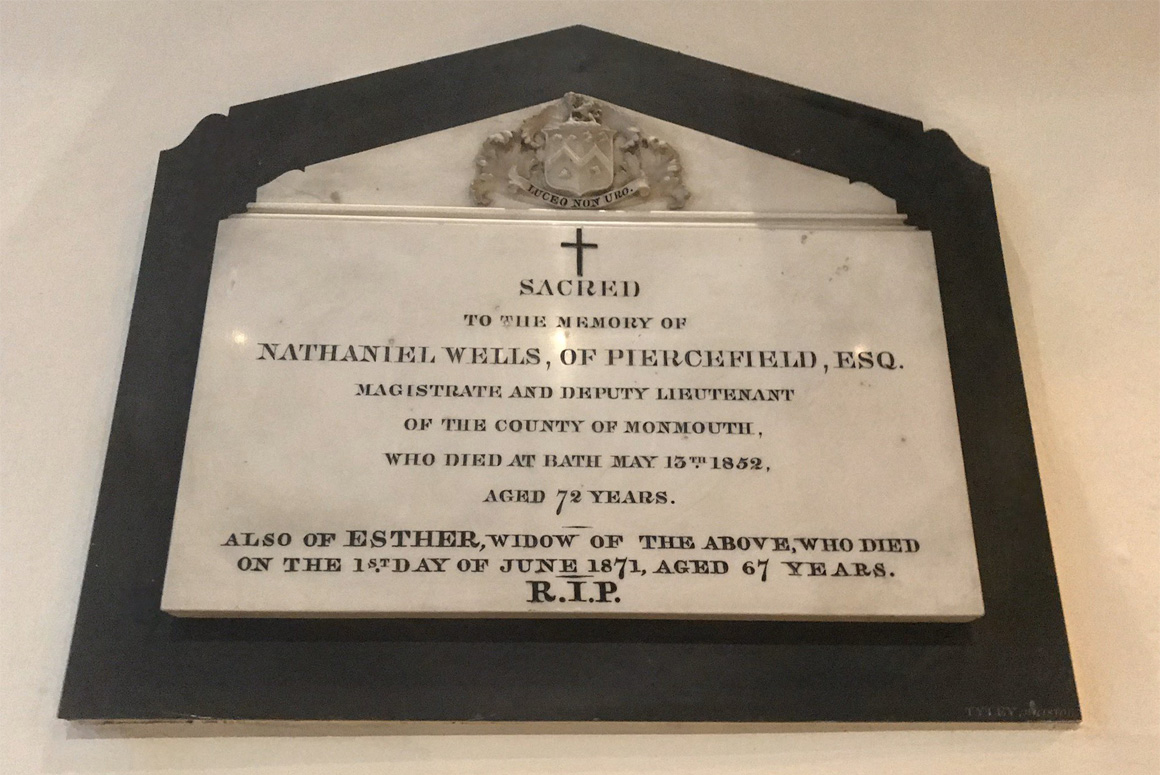

By 1801, he was worth £200,000, which was just as well, because in June that year he got married, to Harriet Este in fashionable St George’s Church, Hanover Square, London. She died in 1820 (aged 40) after providing Wells with ten children (all bar one survived into adulthood). He remarried in 1823, to Esther Owen (when he was 44, and she was just 19). Ironically, Esther’s sister was the daughter-in-law of the abolitionist William Wilberforce. She died in 1871 after providing Nathaniel with a further twelve children between 1824 and 1846, only seven of whom survived into adulthood. Coincidentally, both wives were the daughters of Anglican clergymen.

Meanwhile, Wells was becoming quite the local country gentleman. He bought Piercefield House, Chepstow, from John Wood in 1802, paying £90,000 cash, and continued to add to the estate until it reached almost 3,000 acres. In 1804 he was appointed Churchwarden of St Arvans Church and held that post for forty years. A few years later he became a county magistrate, the first-ever black Justice; and in 1818 he was made Sheriff of Monmouthshire, the only known black sheriff.

To cement his position amongst the local county set, in 1820 he donated the tower to St Arvans Church – a distinctive octagonal tower built from local red sandstone – which is still a prominent feature of the church. Also that year Wells was commissioned as a lieutenant in the Chepstow Troop of the local Yeomanry Cavalry, making him only the second black person ever to be commissioned into the Armed Forces, and no more black officers are known of until almost 100 years later. The yeomanry was raised by the Lord Lieutenant of the county, and was not very well trained or disciplined (a fore-runner to ‘Dad’s Army’ by all accounts). Wells’ military service was not just an honorary role; he took part in action against striking coal-miners and iron workers in South Wales in 1822, but the exact location remains unspecified. His leadership qualities appeared to be somewhat lacking, as it turned out. The strikers were blocking a road and hurling stones down on anyone trying to get through; the yeomanry couldn’t shift them and it was only with the arrival of the regular cavalry, the Royal Scots Greys, that the road was cleared. Perhaps it was as a result of this incompetence that he resigned his commission later that year.

However, he continued to live out his role as ‘country gent’; in 1832 he was on the committee of the Chepstow Hunt. Again, ironically, when slavery was abolished in 1833, he joined forces with other British slave owners and refused to free his slaves, demanding compensation from the government for his loss of ‘property’ and was awarded £1,400 for his 86 slaves on St Kitts. Wells was living at Piercefield at the time of both the 1841 and 1851 censuses but soon after moved to Bath where he died on 13th May 1852, remaining so wealthy that he could leave £10,000 to each of his children. He was buried in the graveyard of St Swithin’s Church, Walcot, Bath; the plot (392) is unmarked due to clearance of the headstones at some time, but there is a memorial tablet to him in St Arvans Church.

Sadly, we have no portrait of Wells. A landscape painter who met him in 1803 noted in his diary: “Mr Wells is a West Indian of large fortune, a man of very gentlemanly manners, but so much a man of colour as to be little removed from a Negro.” The only available image is an artist’s impression to be found in Chepstow Museum.

Finally, what of Piercefield House and estate? After his death, it was sold to John Russell, who owned the neighbouring Wyelands estate. Russell was a coal and iron-master who sold the estate in 1861 and used the money to set up a trust for the families of the 146 miners killed in the 1860 disaster at his Blackvein Colliery, Risca, in the west of Monmouthshire – a touch of conscience or ‘blood money’ recycled? The new owner of Piercefield was Henry Clay who lived in the house until his death in 1921, aged 96, but did little to maintain it. By then it was in a sad state and Clay’s family sold the house and much of the estate to a company whose directors were all members of the Clay family. The entrance to the estate can still be seen today, from the A466, which runs north from Chepstow up the Wye Valley. You may recognise it as the entrance to Chepstow Racecourse because the Clay family company was called Chepstow Racecourse Company. Piercefield House, or what’s left of it, is still there, a sad or fitting memorial to one Monmouthshire’s strangest slave owners.

Words: Roger Evans

Image: Piercefield House – Present Day – Source (CC BY-SA 2.0)