We went to Llanrwst to see a coffin. Not an ordinary coffin, but one the greatest treasure of Wales, the sarcophagus of Llywelyn Fawr or Llywelyn the Great, Prince of Gwynedd and, for a short time in the twelfth century, the ruler of most of Wales.

Llanrwst is a very attractive town in North Wales, with the neat Ancaster Square at its centre and the marvellous Pont Fawr, a beautiful but narrow three-arch stone bridge crossing the river Conwy, built in 1636 and said to have been designed by Inigo Jones. Today it seems to be dominated by the traffic that inches it’s way through the narrow streets, but there is an undeniable sense of the past here and nothing evokes it better than the sarcophagus in the church of St Grwst.

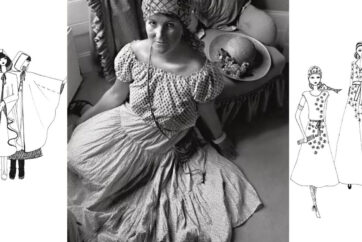

Feature image: The sarcophagus of Llywelyn Fawr.

Llywelyn was reputedly born in Dolwyddelan Castle, near Betws-y-Coed, perhaps in 1172, into the royal family of Gwynedd and led a tempestuous life in turbulent days. His father, Iorwerth, was heir to Owain Gwynedd, the ruler of North Wales, but this could never guarantee the young Llywelyn a position of power in those fractured times. In fact, vicious family rivalries were more likely to secure for him a violent death rather than a crown. His most dangerous enemy was his uncle Dafydd, who had been happy to kill his own brother whilst taking control of Gwynedd. But even as a young man, Llywelyn was a formidable opponent and in 1194, at the age of 22, he led a successful uprising against Dafydd and defeated him in battle at Aberconwy.

Dolwyddelan Castle, Conwy

He sent Dafydd into exile to Ellesmere and shared Gwynedd with his cousins, Gruffudd and Maredudd, who took the lands to the west of the River Conwy with Llywelyn ruling the lands to the east. When Gruffudd died in 1200, Llywelyn began his acquisition of territory and power. He expelled Maredudd, and presented himself as the overlord of the whole of North Wales by capturing the castle at Mold. He next invaded southern Powys, the territory of Gwenwynwyn, an important Welsh rival. Llywelyn had quickly established himself, firstly as the most significant man in Wales and then as a genuine threat, both to English lords along the border, and to King John himself.

In 1205 in recognition of the status he had now achieved, John offered him the hand of his daughter Joan, or Siwan, in marriage. The relationship between the two rulers was always a fragile one, though initially the alliance gave Llywelyn greater status. In 1207 when the English apprehended Gwenwynwyn at Shrewsbury, Llywelyn annexed his lands and rebuilt Aberystwyth Castle as a symbol of his success.

The greatest threat to the Welsh, apart from-as always – themselves, was King John and he started to have concerns about the extent of Llywelyn’s influence. An English army, supported by Gwenwynwyn, and other Welsh leaders agitated by Llywelyn’s rise to power, invaded Gwynedd. When Llywelyn’s army immediately retreated to the hills, John’s army preferred to withdraw to England rather than starve in ravaged Wales. They then returned three months later, marching right across the north to occupy the Welsh royal palace Garth Celyn on Menai Strait and to set fire to Bangor for recreational fun.

Llywelyn sued for peace, using Siwan as an envoy to her father. The subsequent peace terms were a significant set-back for him. He lost the land west of the Conwy and forfeited 20,000 cattle and 40 horses. It was a temporary success. When Aberystwyth was garrisoned with English troops, Welsh leaders, interpreting this as the beginning of an annexation, displayed unusual unity by fighting with Llywelyn and pushing the English back. Llywelyn seized Shrewsbury and went on to take large parts of south Wales.

St Grwst Church, Llanrwst

It was not a good time for John, who was already in serious difficulties with his own barons over the extent of royal power, and the Welsh supported their rebellion, which culminated in the Magna Carta of 1215. Nineteenth century Welsh historians saw Llywelyn glowering fiercely over the shoulder of King John and dictating to him clauses in the Magna Carta relating to liberty and democracy. This is romanticising the man and history. His attempt to unite Wales was not an expression of a national self-determination, but rather of personal ambition, but it certainly fuelled a sense of Welsh identity that still thrives.

By the time King John died in 1216, Prince Llywelyn, at the age of 44, had become the dominant power in Wales, holding a council at Aberdyfi in order to distribute land to the other ruling families and thus, vainly perhaps, trying to control their internecine squabbles. You would like to think that perhaps he had a chance to enjoy this brief period of peace, in a life defined by war. The poet, Llywarch Brydydd y Moch, said that’ Llywelyn, though in battle he killed with fury, though he burnt like outrageous fire, yet he was a mild prince when the mead-horns were distributed.’

At Easter 1230 William de Braose 10th Baron of Abergavenny, a political prisoner, who was negotiating the marriage of his daughter Isabella to Dafydd, Llywelyn’s son, was found together with Siwan in her husband’s bedchamber. I have always liked to think that he was offering her advice on how best to colour-co-ordinate the soft furnishings, but certainly her husband didn’t see it that way.

Llywelyn wrote to William’s wife with some regret, to explain what had happened and saying that he had no option but to hang her husband. In the most important part of the letter he asked if the marriage between Isabella and Dafydd was still on, in her opinion.

She said it was and William was duly hanged on the marsh below Garth Celyn, a humiliating execution for a nobleman. Siwan was placed under house arrest for a year but was forgiven and the couple were re-united, their emotional attachment going far beyond the political origins of their marriage.

She died at Garth Celyn in 1237 and Llywelyn’s grief was recorded by contemporary writers. He had some sort of stroke a short time afterwards and effectively power passed to his son Dafydd. He died in 1240, a chronicler recording that “the lord Llywelyn ap Iorwerth son of Owain Gwynedd, Prince of Wales, a second Achilles, died having taken on the habit of religion at Aberconwy, and was buried honourably.”

Seal of Llywelyn ap Iorwerth (d. 1240)

One of the great things about the story is the artefact itself, that coffin. It sits serenely in the Gwydir Chapel in the beautiful Church of St Grwst where you can get close up to it. One of the great treasures of Welsh history, nine hundred years old and holding such stories. The bones have gone, of course, and even when empty it has had to seek sanctuary in a number of places over the centuries.

Llywelyn was initially buried beneath the High Altar in Aberconwy Abbey. When it was demolished to make way for Conwy Castle, the coffin was moved to a newly-built abbey at Maenan, where it stayed until the dissolution of the monasteries in 1536. It was next taken to St Grwst’s in Llanrwst, a church built by the royal family of Gwynedd. It was neglected and forgotten, spending many years buried beneath rubbish, but for the past 200 years the Gwydir chapel has been its home. It is interesting to note that Siwan’s sarcophagus, which featured in this series some time ago and which you can find in Beaumaris, is very similar, with tests showing that the stone came from the same quarry.

A small fragment of what is supposed to be the missing lid of Llywelyn’s coffin, was found buried at Gyffin, and was built into the porch of St. Benedict’s Parochial Church there. But the bones? Where are they? Some say they fell overboard when the coffin was moved from Aberconwy Abbey. Others say that they were buried secretly in the village of Pentrefoelas near Betws y Coed. But they are certainly not inside the coffin. I know. I have checked.

Words: Geoff Brookes

Illustration: Charlotte Wood