He was as Welsh as they come yet born in Manchester. That’s just the first oddity in the life of David Lloyd George, the only Welsh Prime Minister of the UK and our only PM to speak Welsh as a first language.

Born of Welsh parents, and the son of a schoolmaster, David’s English baptism was brief. When he was just two, his father died, and the family moved to Llanystumdwy, near Criccieth, where David’s cobbler and Baptist minister uncle, Richard Lloyd, lived. Apparently, Lloyd spotted the intrinsic genius of the young prodigy and took on his education. If we feel like lauding Lloyd George for his brilliance, then we should also pay tribute to his uncle, who bestowed religion, industry, oratory, radicalism and Welsh nationalism on the youngster: quite a heady cocktail. We should also lob in Nonconformity and Liberalism.

Lloyd George’s first career was as a solicitor (partly self-taught, his mastery of French and Latin enabled him to embrace the law). He became articled to a firm in Portmadoc (1879), passing his final exam five years later. His first foray into politics occurred in 1890, by which time he was 27. He was elected as Liberal MP for ‘Caernarvon Boroughs’, a seat he held for close on 55 years. From 1905 to 1908 Lloyd George was President of the Board of Trade and was at the helm when three important acts were passed (the Merchant Shipping Act and Census of Production Act, both in 1906, and the Patents Act, of 1907).

Come April 1908, Lloyd George, now aged 45, had risen to the heights of Chancellor of the Exchequer, a post he held until 1915. It was during this period that his zeal as a social reformer really came to the fore, chiefly with his Old Age Pensions Act (1908) and National Insurance Act (1911), plus the famous People’s Budget (1909-10), which was rejected by the House of Lords, leading to a constitutional crisis and the passing of the Parliament Act (1911), which curtailed the power of the Upper House. Lloyd George gave us state pensions and declared war on poverty at home.

During the lead up to WW1, Lloyd George had been widely regarded as a pacifist. He was also known for sticking up for the underdog though and had railed against the Boer War for this reason, viewing the struggle of the Boers as not dissimilar to his own countrymen’s fight for national rights. It was smaller country syndrome. Come 1914, and Germany’s assault on little Belgium, Lloyd George was nothing if not consistent. Any pacifist tendencies were swept away in a rage of indignation.

The ‘Shells Crisis’ saw the 52-year-old Lloyd George appointed Minister of Munitions in May 1915. His tenure of just over a year sorted out the problem of lack of supplies and marked him down as a potential wartime PM. He might not have got the chance, as he was due to depart on ‘HMS Hampshire’, for Russia, in June 1916, but was prevented from embarking by other demands. The ship hit a German mine and sank with 737 deaths, including Secretary of State for War, Lord Kitchener (12 survived). Lloyd George’s moment came quickly, however, as he became Secretary of State for War himself (July 1916), and then Prime Minister in the December (succeeding Herbert Asquith), a post he held until the end of the war, and beyond, until October ’22. Lloyd George remains the only Welsh PM of the UK (Neil Kinnock having lost General Elections in 1987 and 1992).

Lloyd George’s forceful war policy is held to have made him ‘the man who won the war’ (a compliment paid by none other than Adolf Hitler, who’d have some grievances he’d want to put right, courtesy of WW2). There was a real possibility the two men could have faced off as rival war leaders in that later conflict (read on). When WW1 was won, Lloyd George was one of the so-called ‘Big Three’ who presided over the punishment of defeated Germany, and its allies, in the subsequent peace treaties (the other two being the French and US leaders). The view is that the inspired war leader was also a brilliant peacemaker, although he may have tried too hard to satisfy the demands of small nations (smaller country syndrome again), which stored up future problems, some of which Hitler exploited. Britain would reap a whirlwind even earlier, e.g. in Greece (the Greco-Turkish War, 1919-22, where Britain was on the Greek side).

“…a body of 500 men chosen at random from among the unemployed.”

David Lloyd George, 1909

Describing the House of Lords in inimitable fashion

Great war-leader, peacemaker, social reformer, Lloyd George was all of these, but he also presided over a split in his Liberal Party, which never healed, and was the genesis for it being supplanted and becoming a mere fringe party hoping to hold a balance of power. That peace-making inclination showed itself in 1921, when Lloyd George treated with Sinn Fein in Ireland, the result being the Irish Free State (today’s Southern Ireland or Eire). This was immensely unpopular with the Conservatives, who’ve always been the party of Union (the Conservative and Unionist Party). This led to Lloyd George’s downfall in 1922 and the demise of his party. I suppose you could call him a conviction politician, putting principle ahead of party. The great man retained his Caernarvon seat, however, until the year of his death (1945) and was made an earl the same year (Lloyd-George of Dwyfor).

Lloyd George took to authoring, writing his ‘War Memoirs’ (1933-36) and ‘The Truth about the Peace Treaties’ (1938). It put him on a par with Sir Winston Churchill, who also scribed, including his account of the war he presided over (‘The Second World War’). Intriguingly, Lloyd George was favoured by many to take over as PM in May 1940 at the time of the Norway Debate, but he was by then 77 and was not keen. David had already experienced his ‘man and the hour’ moment: perhaps it was too much to expect him to do it twice. Maybe one of the great attributes of leadership is to know when to step aside. The mantle passed to Churchill instead, despite the fact he had been more culpable than anyone for the Norwegian debacle. The rest as they say is mere history.

David Lloyd George died as that second conflict drew to a close, 75 years ago, on 26th March 1945, aged 82. D-Day lay a little over two months away. If I had to pick out one quote of his that summed up his essential mantra, it would probably be, “a body of 500 men chosen at random from among the unemployed.” (He was describing the House of Lords in inimitable fashion). Yes, he had a scathing wit and employed it to full effect on many occasions.

Words: Stephen Roberts

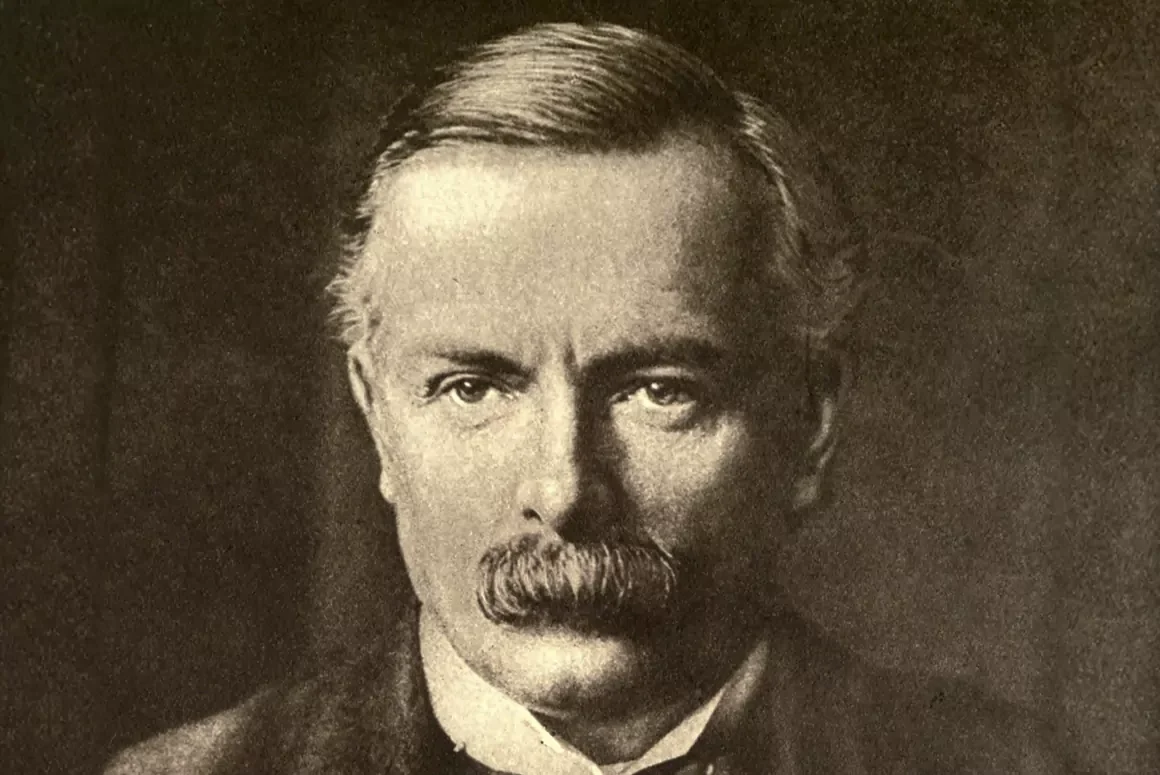

Feature image: Lloyd George in 1915 [Source]

First published in Welsh Country Magazine Jan-Feb 2020

![David Lloyd George Lloyd George (centre) at the Paris Peace Conference after WW1 with French PM George Clemenceau (left) and Italian PM Vittorio Orlando (right).[Source]](https://www.welshcountry.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2025/01/LG-5.webp)

![David Lloyd George Lloyd George pictured with Winston Churchill in 1907, when they were both members of the Liberal Party.[Source]](https://www.welshcountry.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2025/01/LG-2.webp)

![David Lloyd George Lloyd George statue at Caernarfon Castle (1921), in recognition of his service as local MP and prime minister.[Source: Libby Norman (CC BY-SA 3.0)]](https://www.welshcountry.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2025/01/David_Lloyd_George_statue_next_to_Caernarfon_Castle.webp)