“W-w-wow!”

A gasp burst from between my daughter’s lips.

“Wow!” That gentle, whispered exclamation again as her head swivelled from side to side, tipped backward to look up and then down, as though attached only by a loose spring. Every last hint of teenaged cynicism melted away as she did her best to take everything in through her new contact lenses all at once, gazing in utter amazement at even the most minute and mundane things in this flood of new clarity: a woman struggling to manage armfuls of shopping; a dog straining on its leash, pink tongue lolling like a limp ribbon; vases of wilted flowers perched upon the windowsills of the flats opposite where we stood.

We stayed that way for a while, her sitting on the low riverside wall near the optician’s shop, watching the flow of the river as it rippled by below, and then following with an airy swirl of her neck the looping arcs prescribed by the gulls that swooped and skriked above our heads beneath the slow onward roll of tumbling cloud banks. Of particular interest were the hills behind the town centre and their myriad shades of green – grass, trees, gorse bushes punctuated by their pin pricks of yellow, leading her to exclaim to no-one in particular and yet to the entire world at the same time: “I never knew there were so many shades of green!” Everything she had ever known as normal suddenly shunted sideways in a seismic optical shift, redrawing her world in real time. After another minute or so, she turned to me, her face split by a huge grin, and asked, “Is this what you see?” I hugged her, and almost burst into tears.

This shared moment of epiphany left me almost as thunderstruck as my daughter. How we take our sight for granted, I thought to myself, captivated by the spectacle of this young lady made a gawping little girl again by the simple gift of clear vision, watching her actually see the world rather than simply looking upon an occluded version of it. Little more than a slight lexical tilt at first, the angling of a lens to catch the light differently; this tiny linguistic alteration in reality truly creates a huge, and important, shift in perspective.

*

For as long as I can recall, I have chosen to begin the academic year each September by showing to the students in my A-Level Media Studies and English Literature classes, Rene Magritte’s 1929 painting The Treachery of Images. The painting of a bent billiard smoker’s pipe, along with the caption ‘Ceci n’est pas un pipe’ – this is not a pipe – often raises more than a few eyebrows and gentle laughs. Has he lost his mind? I imagine them thinking as they mutter to each other about where the point may be leading. When I eventually explain to them that Magritte was correct, that it is not actually a pipe, but a Powerpoint presentation of a digital image of a painting of a pipe, starting to unpick the relationship between the looked-at and the seen, the literal and the allegorical, then the penny starts to drop. It is at this point that the conversation really begins, leading us off into a maze of metaphorical alleys as the school year eventually unfolds lesson by lesson.

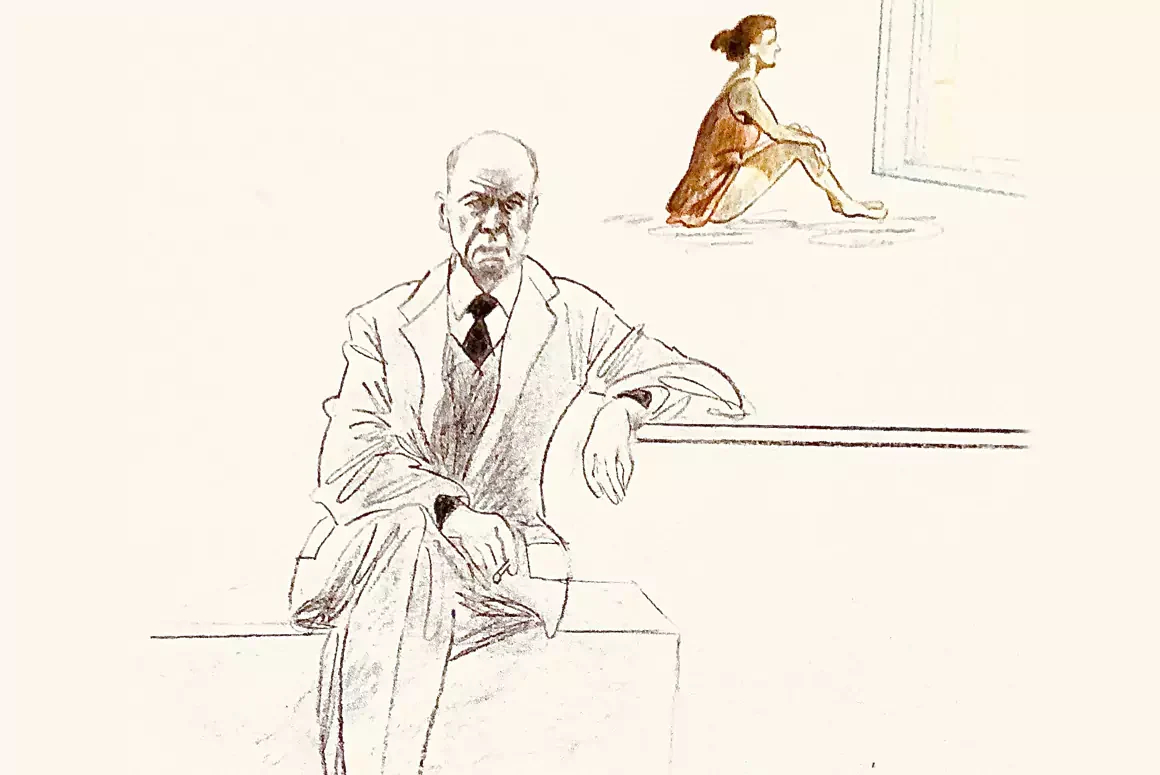

It is appropriate, I think, to talk of artists here, for two of my favourites – Edward Hopper and Eric Ravilious – as different as can be, exemplify perfectly how, when it comes to actually seeing the world around us, everything is up for grabs. Their very different experiences of life coloured and formed their realities, the lives and scenes they captured in paint.

I have always admired the works of Eric Ravilious for their feel of an onward flow in starkly poignant contrast to the life of the artist himself, cut short by a tragic disappearance and presumed death during an observation plane flight during World War II. Through his use of colour, line and perspective, Ravilious always seems to draw the eye onward, pulling us into , and through, his landscapes, seascapes and other scenes, so that we journey with him. For what was he searching? I often think when looking at his work. What is it that the road or river leads to, just over that hill or around that corner where paths, waves, hills and even shadows wend their ways ever onward? Like a thread, these routes and tracks seemingly link the energies of one painting to the next in an unbroken line, celebrating the quintessentially idyllic British pastoral and the longing for its continuation, fighting, through art, the anxieties of war and the terrible threat posed by such a tyrannical enemy.

Ravilious invites us to see – what is around the next corner, the next bend in the river – but we have to see it for ourselves, not by looking at the paintings but by looking into them and through them to gain insight. All I need to do is to see these images, really see them in their onwardness, for want of a better word, and I am in – in the landscape, in the mood, in the same moment as the poet Edward Thomas when, from a train at Adlestrop station, just before another war, in another part of England at another time, he saw the same things as Ravilious in his own thoughts and insights when “…for that minute a blackbird sang/Close by, and round him, mistier,/Farther and farther, all the birds/Of Oxfordshire and Gloucestershire” carried him off with their song. Just like Ravilious, Thomas marches away with us into an imagined pastoral scene somewhere far beyond his immediate ken, an idyll basking in the sun, and yet soon to fall into darkness beneath the cloud shadow of conflict.

Hopper’s work on the other hand, I love for different reasons. Whatever the scene, be it a sailing boat, a view through the window of a sun struck gable, it always seems to be a moment caught in time, brilliantly slowed to a standstill so that a viewer can contemplate the image at their own pace. Dominated by figures of women, Hopper’s works reflect the strong female presence in his early life, but even more arresting is the presence, even in the brightest and sunniest of his paintings, of prominent shadow that always seems to make itself felt as well as seen, representative perhaps of those years of struggle in Manhattan, toiling to finally make a name for himself, a reality hidden by the later success that he would find. Always there in the background and sometimes even in the foreground, like a cloud of self-doubt, it is so easy to overlook. Such darkness and uncertainty, however, never go unnoticed by those with an eye to see them, including E.B. White: “…the residents of Manhattan are to a large extent strangers who have pulled up stakes somewhere and come to town, seeking sanctuary or fulfilment…The capacity to make such dubious gifts is a mysterious quality of New York. It can destroy an individual, or it can fulfil them.”

An accomplished art critic would likely tear these opinions to shreds and dismiss them out of hand yet, even if this were the case, I would hold fast to them. Whatever the realities may be behind the works of these two great artists, and any other artist or writer for that matter, the fact remains that it is left to the viewer to look, then see, then interpret the works in their own way, bringing their own meaning to what is there in paint before them. Eyes are famously oft-labelled ‘the windows to the soul’, allowing us to see the real essence of a person, but if this is the case then surely it stands to reason that the inverse is true, and that the soul of a person looks outward too, colouring how we see and interpret the world around us.

The distinction in the process of the act look – see – interpret seems somewhat strange here on paper as it describes a process that should, and did, happen naturally, but which is now no longer the case. Here in our fast-paced, relentless society, we are so bombarded with images and information that we barely have time to see, only to look, flitting from one image to the next, barely ever settling on one thing for long enough to truly take it all in properly. I am, of course, approaching the matter from a 21st-century perspective and, although less than a hundred years on from the heydays of Hopper, Ravilious and White, it might as well be centuries for all the change that time and its progress has wrought over those years. Yet the problems we have with seeing remain the same.

In 1911, the Welsh poet W.H. Davies famously wrote the line “We have no time to stand and stare”, highlighting in a beautifully understated way that a lack of sight and, subsequently, insight, is certainly not a twenty-first century problem. Over a century before Davies’s words, William Wordsworth observed how “…with an eye made quiet by the power/Of harmony, and the deep power of joy,/We see into the life of things,” essentially linking the act of seeing with the importance of quiet and contemplation, but more importantly emphasising the idea that when this happens, when we do actually take the time to “stand and stare”, true insight is given free rein. In the midst of the industrial revolution, its advancements, its relentless momentum and the urbanisation sweeping through “…mid the din/Of towns and cities” of “…this unintelligible world”, Wordsworth recognised the importance of stopping, looking, contemplating and truly seeing things not just for what they were, but for what they could be. True seeing is not just about the details of what is around us, but the possibilities inherent in interpreting and even shaping these things through the power of imagination.

Wordsworth’s contemporary William Hazlitt, another writer gifted with true sight, wrote that “Distant objects please, because, in the first place, they imply an idea of space and magnitude, and because, not being obtruded too close upon the eye, we clothe them with the indistinct and airy colours of fancy”, and it is this final idea of seeing, foresight, supported by Edgar Allen Poe’s poetic assertion that “All that we see or seem/Is but a dream within a dream”, that is perhaps most important to human existence.

When we to take that time “to stand and stare”, and to contemplate, we are able to not just see the world around us but to envisage our own version of it. Those dreamers who take a moment to gaze beyond the physical are those who begin to populate it with objects and ideas, routes and plans unique amongst billions, one of the key driving forces behind the development of the human race. Unfortunately, it seems that we, as a society, have less and less time to accommodate such dreaming these days, to make space for sight, insight and foresight, the three pillars that afford us a platform upon which to build a complete picture and to consider not only what we see, but also how we see, and how we wish to see.

With each year that slips by, with every September that arrives, it seems that these pillars seem a little more eroded by the sweeping winds of time and modernity. Magritte’s pipe takes a little more discussion; its concepts take a little longer to garner the attention of the students who move through my classes, and to slow them down to a moment of clarity that steers their path in a slightly altered direction. Still, I and others like me continue to spread the word, to open our students’ eyes and try to help them so see through those acts that allow us to become visionary in every sense of the word, taking in the whole world, blink-by-blink, just like Wordsworth and Hazlitt, like Ravilious and Hopper. Just like a teenaged girl seeing the world around her in full, wonderful glorious colour for the very first time.