As always, we were seeking a grave. Above Porth and in driving rain I explored the Independent Chapel in Cymer. It is derelict now and I couldn’t get past the scaffolding to the graves. The chapel was once an important place – the earliest independent chapel in the Rhondda. But now ignorant traffic hissed through the busy junction and the world and life of Daniel Thomas seemed smothered and lost.

He was buried here in January 1884 in torrential rain “in the presence of a vast concourse of people.” Because this was Daniel Thomas – a hero.

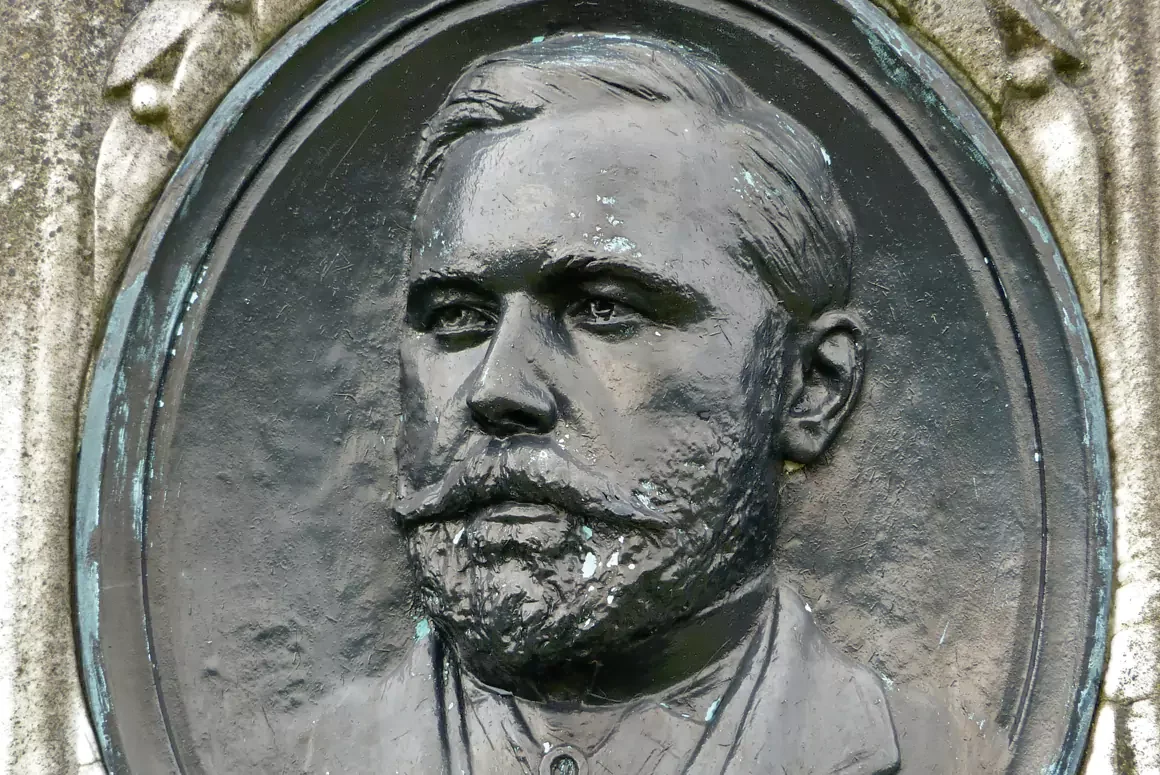

Feature image: Black painted bronze bust of Thomas by W Davies

He was born on 15 January 1849; his father was a mine owner and he was educated by Mr Lloyd of Pontypridd, “a gentleman who has trained for colliery management the majority of the Glamorgan colliery managers.” Daniel was described as self-willed and decisive.

After serving as assistant to his father in the management of Brithwennydd Colliery, he succeeded him as manager in 1872. He always knew the price of coal; Victorian industry and enterprise were paid for with the lives of miners. Perilous lives, fragile lives.

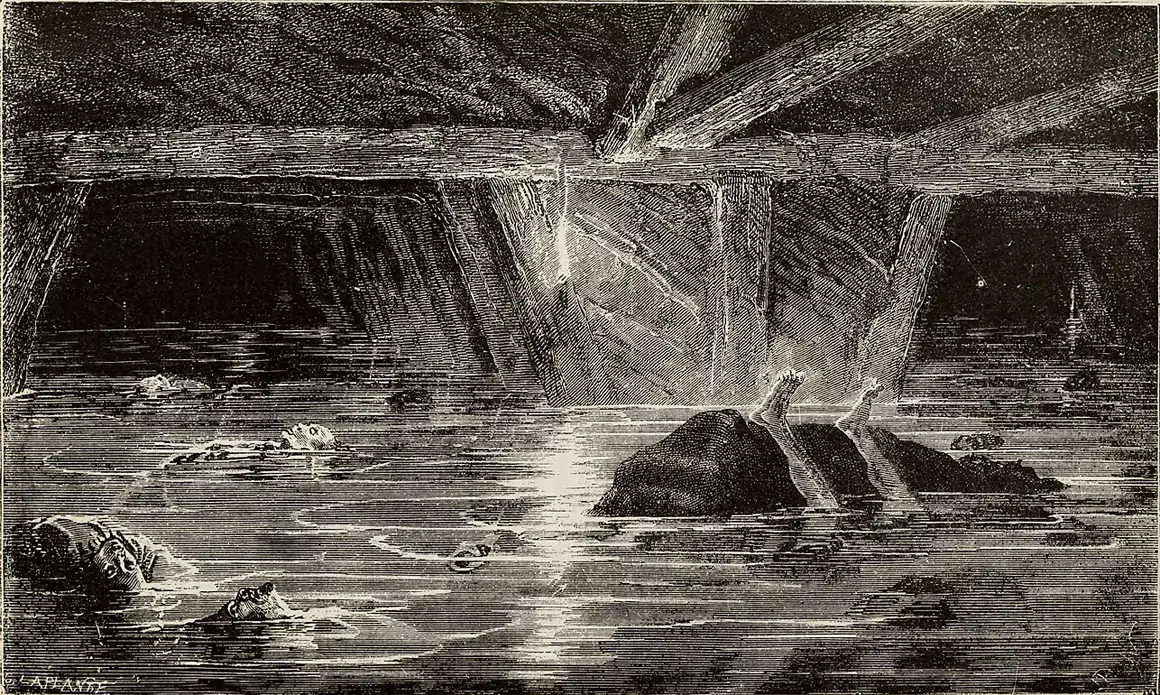

On 11 April 1877 at the Tynewydd pit a miner inadvertently hacked his way into the flooded workings of an abandoned colliery. There was a catastrophic inundation. Four miners were instantly drowned, others were trapped. Four were recovered on the first day of the rescue operation and although three rescuers died, five others remained trapped underground. Their plight seized the popular imagination. There were daily reports of their plight in newspapers across the country. The Home Secretary gave daily progress reports to the House of Commons. The Pontypool Free Press reported that the Queen had “constantly telegraphed for fresh information, in which anxiety she was joined by all classes throughout the country.”

The five men had no food and only filthy water to drink. Initially they ate the wax dripping from their candles for a few days until the profound darkness of the flooded pit enveloped them. They could hear their colleagues digging but could not communicate with them and the water continued to rise around them as they waited. Soon it was up to their chins as they prayed and sang hymns, hammering on the coal face as much as they could with their picks. One of them was David Hughes, 14 years old; his father and brother had already drowned.

Artists impression of the Tynewydd Colliery disaster at Porth 1877

The rescue was led with considerable skill and expertise by Daniel Thomas and his brother Edmund. They went down the shaft and remained below throughout the operation, encouraging the diggers “by their presence and example.” Miners told reporters that “it was the confidence that they felt in these two brothers which gave them courage to volunteer and face the perils of water and fire and suffocation.” They had huge problems to deal with as 113 feet of rock and coal had to be removed to reach the trapped men. Eventually a group of diggers led by Isaac Pride reached them and they were dragged out, weak and incoherent. They had been trapped for 10 days.

Queen Victoria subscribed £50 to the Tynewydd disaster fund and created a new order of merit. She declared “that the Albert Medal, hitherto only bestowed for gallantry in saving life at sea, should be awarded for similar actions on land, and that the first medals awarded for this purpose should be conferred on the Tynewydd rescuers.”

It was, briefly, a national event. There was a song, “The Gallant Men of Wales,” sung at a Crystal Palace fete in aid of the Tynewydd Inundation Fund.

Dark, dark! No food! And higher still

The hungry waters rose!

But hark! A knocking at their tomb!

A sound of mighty blows!

The little lad wakes from his dreams,

The bowed men hold their breath.

They come! They come! Their comrades true-

To rescue them from death.

A reporter confirmed that some of the fund would be spent supporting the youngest survivor. “I was much struck with the delicate and what I may truly call the refined look of the boy David Hughes who is only 14 years old and will be sent to school, as his education has hitherto been much neglected.” Perhaps he was rescued from the pit for a second time.

Daniel Thomas and Isaac Pride received the Albert Medal First Class in a ceremony at the Mansion House in Pontypridd. Others received Second Class medals, including Edmund and other colliery owners and managers. Daniel also received the medal of the Knights Templars of Jerusalem and the medal of the Humane Society.

Daniel Thomas became a local hero. A mine owner perhaps, but one of their own. The Western Mail would later say that he “won the affection of a large section of the workmen by his considerate treatment of all in his employ. He differed from most colliery proprietors by taking a practical and leading part in the management of his collieries. Colliers in the remotest workings never knew what moment of the day Mr Thomas would visit them. He ever took the lead in his own collieries in the performance of hazardous undertakings.” His bravery they said “bordered on recklessness.”

There was a disastrous explosion in the Dinas Steam Coal Colliery on the 13th January, 1879, when many miners were entombed. The colliery was virtually destroyed and ready to be abandoned. Thomas however leased the colliery and made his first task the recovery of the bodies of the men. By the time of Thomas’ death, 49 had been recovered, leaving only six still to be found. He was also able to restore production at the colliery thus boosting employment. He paid out over £5,000 a month in wages.

Memorial to the bravery of Danial Thomas

But in the Naval Steam Coal Colliery in Penygraig his luck ran out. There had already been an explosion in the Colliery in December 1880. 101 miners were killed in a huge explosion. Reports describe the discovery of 16 dead miners in a kneeling position, “death having come to them while they were engaged in prayer.” The pit’s reputation as “a fiery one” was seen again in January 1884. There was another tremendous explosion, so fierce that a child was thrown out of bed by the concussion over half a mile away. The manager had ordered a controlled explosion on a Sunday morning to shatter rocks but it all went horribly wrong. “A straight white column shot up from the pit’s mouth as from a canon, its centre full of fire.”

Men rushed to the pit to see what could be done. Daniel Thomas arrived and took a party down to look for survivors. Thankfully there had not been many in the pit at the time of the explosion but 11 men were unaccounted for.

He led the way carefully through the workings. They found the bodies of men and horses but the air was thick and deadly. Thomas gave the instruction to turn back. But it was too late. He and two colleagues, Edward Watkins and Thomas “Double Strength” Davies, were overcome by the afterdamp – a deadly mixture of carbon monoxide, carbon dioxide and nitrogen.

There was an out-pouring of grief. “Men, whose blue-scarred faces told of a lifetime spent in the Rhondda mines, wept like children.”

His remains “were placed in the dining -room and the canvas was then opened. The features bore the expression of calm repose. Thick dust was in his beard, and his face was begrimed.”

Leave Porth and drive further into the Rhondda along the A4058, to the large cemetery at Trealaw. It is easy to find the impressive memorial to the bravery of Daniel Thomas, situated along the road on the right hand side as you enter.

Leave Porth and drive further into the Rhondda along the A4058, to the large cemetery at Trealaw. It is easy to find the impressive memorial to the bravery of Daniel Thomas, situated along the road on the right hand side as you enter.

The short white marble cenotaph has three engraved panels with a black-painted bronze bust of Thomas by W Davies of Caerphilly. It is a profile which suggests nobility and compassion and displays proudly his medals for bravery. The monument was designed with the front facing the valley where the mines used to be and which is now green and peaceful.

Such memories are disappearing as we bury the past beneath the tarmac, but we must forget neither the heroism, nor the sense of duty that led all those years ago to this shortened cenotaph in the cemetery at Trealaw.

Words: Geoff Brookes

Illustration: Charlotte Wood

Image: Artists impression of the Tynewydd Colliery disaster at Porth 1877 – Source

First published in Welsh Country Magazine July – August 2015