“The whole problem with the world is that fools and fanatics are always so certain of themselves, and wiser people so full of doubts.”

If I tell you that my subject’s bio, in my trusty biographical dictionary, is considerably longer than that pertaining to Sir Winston Churchill, you’ll be impressed and might want to read on. The fact he was also a ‘Marmite’ character (honoured and reviled equally) might also get you interested.

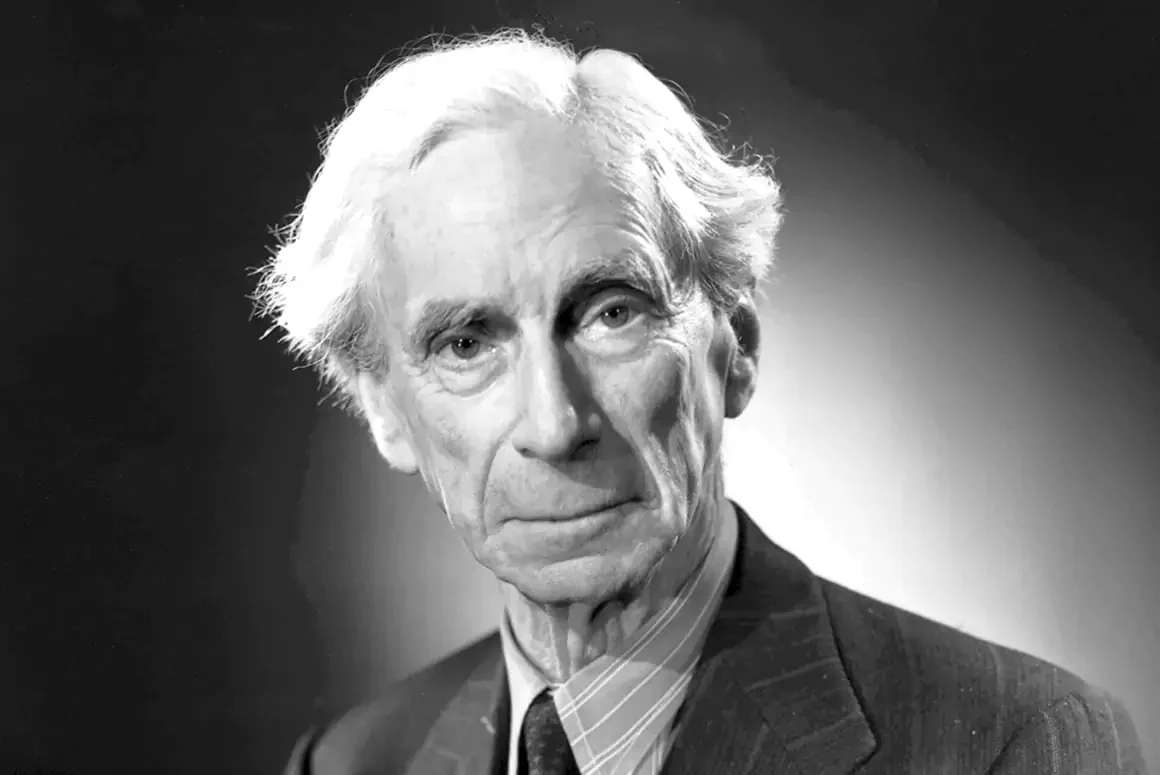

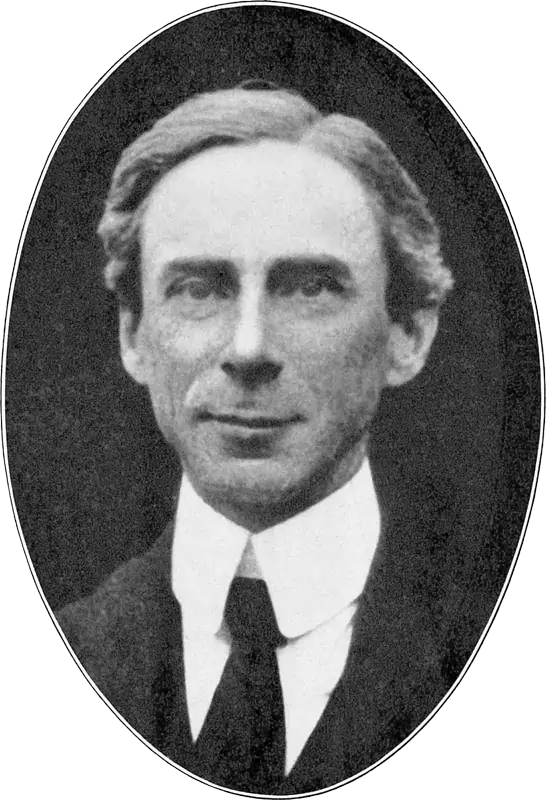

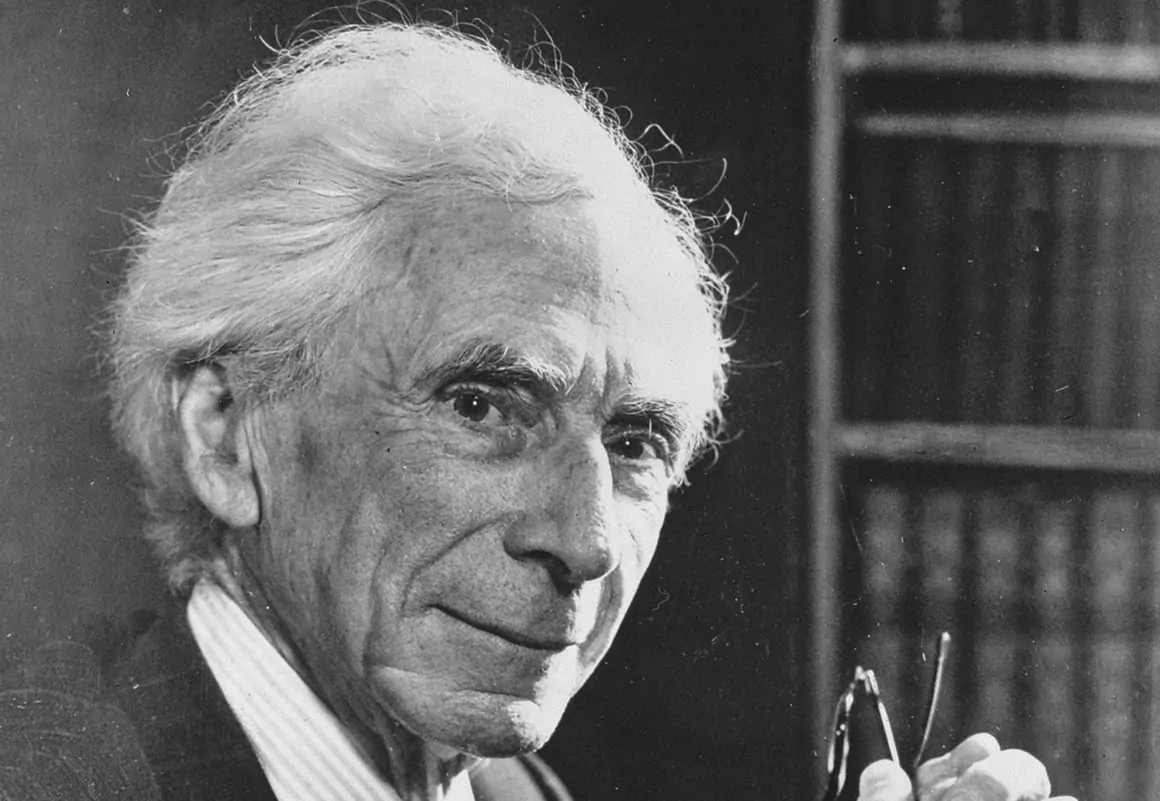

Philosopher, mathematician, historian, writer, essayist, critic and ‘controversialist’, now, I like the sound of the latter. One of our greatest ‘logicians’ and a political activist and utilitarian, maximising happiness and well-being for the majority. I’m liking the sound of this person more and more. He was born in Wales, was the scion of aristocracy and was a Nobel Prize winner. His name was Bertrand Russell.

Born at ‘Ravenscroft’, Trellech, Monmouthshire (18th May 1872), Bertrand was the son of Viscount Amberley, educated at Trinity, Cambridge, and departing with 1st Class Honours in Maths (1893) and then in Moral Sciences (1894); a double-1st in other words.

Born at ‘Ravenscroft’, Trellech, Monmouthshire (18th May 1872), Bertrand was the son of Viscount Amberley, educated at Trinity, Cambridge, and departing with 1st Class Honours in Maths (1893) and then in Moral Sciences (1894); a double-1st in other words.

A colourful life kicked off with a stint as a British Embassy attaché in Paris, then a sojourn in Berlin, where Russell studied Economics and wrote his first tome, ‘German Social Democracy’ (1896), which sounds like essential bedtime browsing. He’d go on to write over 70 books and some 2,000 articles. He also found time somehow to marry Alys Pearsall Smith, in 1894, the first of four spouses (Russell’s first three marriages would all end in divorce).

Russell published his ‘Principles of Mathematics’ (1903), which led on to the ‘monumental’ ‘Principia Mathematica’ (1910-13), which he collaborated on with Alfred North Whitehead (1861-1947), a Kent-born mathematician and philosopher. Russell had actually been a pupil of Whitehead’s at Trinity. Russell was both pupil and mentor, for some of his philosophical ‘methods’ were fully developed by his outstanding student, Vienna-born Ludwig Wittgenstein (1889-1951), with Russell scribing the introduction to Wittgenstein’s ‘Tractatus’ of 1922.

A pacifist during WW1, Russell would be sentenced to six months’ imprisonment in Brixton (1918) for publicly lecturing against the American entry into the war on the Allied side. Russell’s great work, ‘Introduction to Mathematical Philosophy’ was actually written whilst inside. The more one learns about B.R. the more one realises he was no ‘airy-fairy’ philosopher, but a man of conviction. The man of conviction was dismissed from Trinity because of his conviction under D.O.R.A. (Defence of the Realm Act).

Who inspired Russell? Well, apparently, he looked up to John Stuart Mill (1806-73), an earlier philosopher, but also economist and civil servant, who propounded his ideas on liberalism. Russell, for all his aristocratic background, was both liberal-thinking, and an ardent feminist, as Mill had been and at a time when this was decidedly out of kilter with mainstream thought. He offered himself as a Liberal candidate (1907) but was rejected because of his ‘free-thinking’.

Russell changed as a result of the war and his incarceration and he morphed into the ‘controversialist’, who would earn a living by espousing radical causes, that fed into his lecturing and journalism. He visited the Soviet Union, where he met the architects of the Bolshevik Revolution, Lenin and Trotsky, plus Maxim Gorky (1868-1936), the writer and political activist, who was five-times nominated for the Nobel Literature prize, an accolade that would fall, in due course, to Russell. B.R.’s ‘Theory and Practice of Bolshevism’ (1919) was critical of what he’d witnessed in Soviet Russia though, so he was no lackey, but told things how he saw them. Just to continue with his eclectic life, Russell became professor at Peking (1920-21), today’s Beijing.

When Russell’s first wife divorced him, he remarried to Dora Winifred Black (1921), another Cambridge graduate, with whom he ran a progressive school in Petersfield, Hampshire, also setting out his educational theories in ‘On Education’ (1926) and ‘Education and the Social Order’ (1932).

Being divorced for a second time in the mid-1930s rendered Russell’s ‘Marriage and Morals’ (1932) hugely controversial and his lectureship at the City College of New York was brought to an end in 1940 as the local clergy and ratepayers raged against this Englishman, who was now perceived to be an ‘enemy of religion and morality’. They were certainly very different times to today and Russell didn’t always fit. He did extract some modicum of revenge, however, for he succeeded in winning an action for breach of contract.

A third marriage would follow, in 1936, to Helen Patricia Spence, his research assistant for the weighty ‘Freedom and Organisation, 1814-1914’, which was published in 1934. This must have all been ‘grist to the mill’ over in the States. Like Winston Churchill, Russell was in the wilderness, in the 1930s, in preaching against the evil of and threat posed by, Fascism and, eventually, he renounced pacifism, in 1939, as the world lunged into WW2, the most destructive conflict in human history. In the early post-war period, when the USA had a monopoly on ‘the bomb’, Russell would advocate its deployment against Russia, so he clearly felt no great fondness any longer for the Soviets or the Communists.

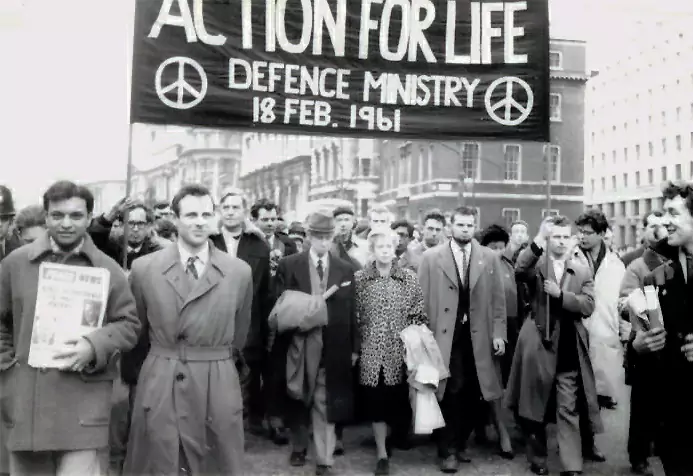

Russell embarked on a new phase in his life, and thinking, from 1949, when he became a leading light in the campaign for nuclear disarmament. He engaged in voluminous correspondence with world leaders, for example, at the time of the Cuban Missile Crisis (1962), and also protested bitterly against the US involvement in Vietnam, none of which was likely to win him any new friends in high places across the pond, although his sentiments may have struck a chord with ordinary Americans who were also having doubts about their country’s Cold War strategy.

Having divorced wife number three, Russell became hitched, for the fourth and final time, to Edith Finch (1952), a fellow-novelist and an American to boot. Clearly not everyone over there had reservations about him. Russell was restored to Trinity and gave the first of the Reith lectures (1949) as he experienced a period of rehabilitation and acceptance.

Arguably, Russell’s greatest achievement, or, at least, the greatest recognition of his singular talents, came with the award of the Nobel Prize in Literature (1950) for his ‘varied and significant writings in which he champions humanitarian ideals and freedom of thought’. I couldn’t have summed it up any better myself. He was an immensely controversial figure, someone who seemed to have leapt from the 18th century, into the 20th and thoroughly wound up everyone around him. He’d write his own tongue-in-cheek obituary for ‘The Times’ (I fancy doing the same myself, but I might not make the ‘The Times’ with it) and has been lauded as the greatest ‘logician’ since the ancient Greeks and Aristotle. Wow! Not bad for a boy from Wales.

Words: Stephen Roberts

Image:

Bertrand Russell and his fourth wife, Edith, lead anti-nuclear protestors in London, February 1961 (CC BY 3.0)

Bust of Bertrand Russell by Marcelle Quinton (1980) (Source | CC BY 3.0)