![]()

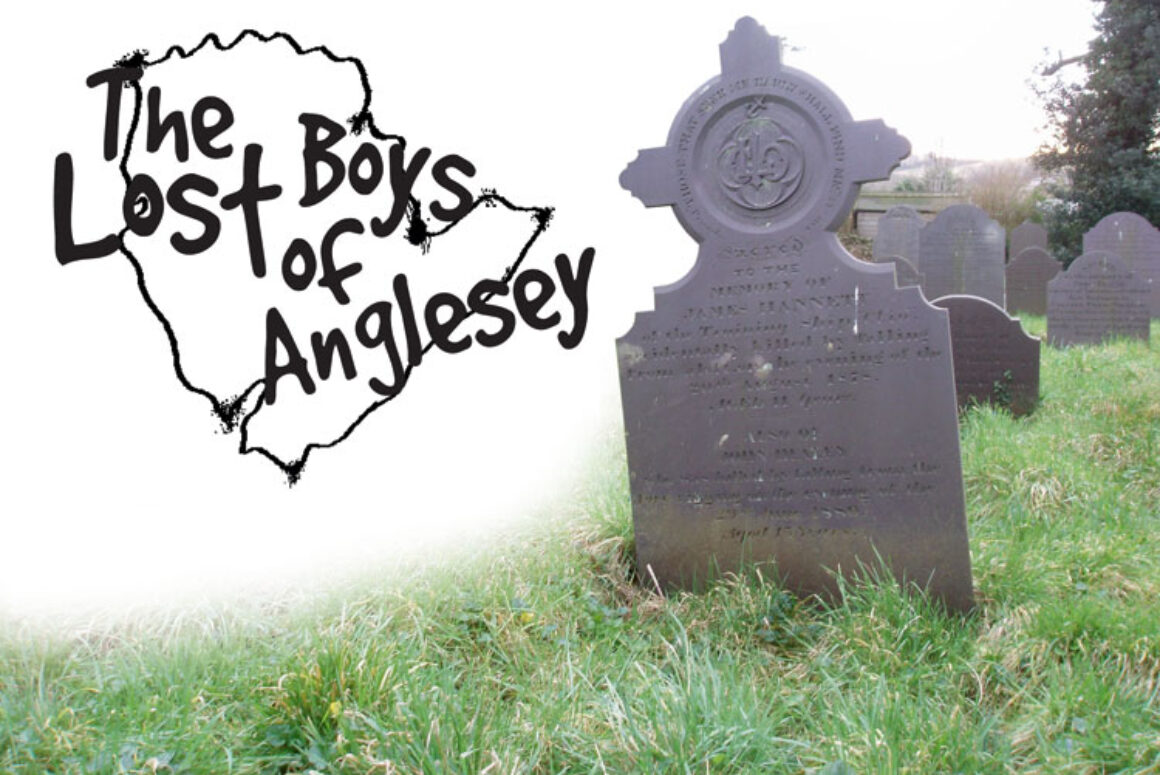

You can find Eglwys St Tegfan in Llandegfan in Anglesey. It is a pretty place which looks down on the Menai Straight and across to the mainland. It is peaceful and well tended, reflecting the history of a hard-working rural community. But there is something unusual in the churchyard. Look carefully and you will find a collection of five very distinctive headstones. When we were there, a flush of snowdrops had gathered in front of one of the stones, like a tribute. It is the least these gravestones deserve.

They each have an anchor and chain design on them and the name of a ship, the HMS Clio. The inscription at the top of each stone is from Proverbs [8:17] and reads, ‘Those that seek me early shall find me’. Are these reassuring words? Or are they chilling? Because when you examine them, you can see that the headstones all are inscribed with the names of young boys.

These stones and these names bring together Anglesey and Montevideo in Uruguay on the same piece of grey local slate, in sad and moving stories. For these are the graves of boys from the industrial training vessel HMS Clio.

What strikes you immediately is the extent of the loss. You will find the names of 29 boys on 5 different headstones which stand lost and neglected, like the boys themselves. The headstones stand now at angles, as if battling against the ocean swell in this beautiful and peaceful cemetery, fighting against the relentless incursion of the long grass.

The Clio was a floating workhouse or orphanage which was moored in the Menai Straight from 1877 to May 1919 and these gravestones commemorate the boys who died on board or later at sea. Their names feature as lists, like a bureaucratic exercise. Indeed, the names of eleven boys are mentioned on one stone, using both sides, as if to save space and cut costs. It is a tragic register from a floating school.

In fact, such industrial training ships prefigured the concept of vocational training that some people today find quite enticing. But there was a sense of finality about it all. Someone else was making your decisions for you. They told you that this is your life, that a path has been marked out for you that you must follow, that your expectations and your horizons have been chosen for you by someone else.

Obviously those involved felt they were doing good work; given their paternalistic view of the world, they never seemed to consider it otherwise. The idea was to help the poor find jobs and in doing so remove boys from the workhouse. The boys were given training in naval life, acquiring the skills and discipline required for teenage boys, while also providing a reservoir of recruits. It was a production line responding to supply and demand, a simple way of plugging the skills gap. As the supervisory board said, do your work well and “worldly success is assured.”

But it was a dangerous world: boys died. There is a report in the ‘Caernarfon and Denbigh Herald’ for 24th August 1878 that a young “lad named Hallett was amusing himself by exercising on the yard arm”, when he fell to the deck. He died 2 days later.

The inquest was held at what is today the Gazelle Inn on the Anglesey side of the Garth ferry. It didn’t take long to find a verdict of Accidental Death, though the coroner did advise the staff “to place nets under the yards whilst the boys were being exercised upon them, the deceased having fallen 60 or 70 feet to the deck.”

“120 boys attended his funeral in charge of Mr. Delaney, the Chief Officer. His coffin was covered in the Union Jack.”

Of course, we notice that the reporter managed to spell the boy’s name incorrectly and give the impression that a Christian name is not important: there is no boy named Hallett in the graveyard. But we know his name. He was James Hannett and he received more respect in death that he ever did in life. He was eleven years old and had been on board for five weeks when he died. He was from Manchester. His father was dead and his mother in prison for an assault, which is why he was there. What else could be done with him?

In death, he shares his gravestone with John Healey who fell from the rigging on 29th June 1880. He was 15 years old. Those nets recommended by the coroner do not appear to have been effective.

The training ship functioned as an orphanage, as a place to park abandoned or difficult boys and give them training for a future life at sea. Indeed, they were described as “scholars training for the sea.” They were from disadvantaged backgrounds or they had already been in trouble. They were generally young and under-nourished. The Census register for 1881 carries details of their birthplaces. They came from all over the country – including William Hodgkins, born on a barge.

Bullying was not uncommon in such an environment. In January 1905, one boy, William Crook, was assaulted by older boys, resulting in fatal head injuries. Poor William, his name appears with ten others on a small stone sinking into the long grass and the soft earth. It is a small headstone but also a double-sided one, necessary to fit on all the names…

It was a harsh regime with limited food and accommodation. The boys slept in hammocks which could be very cold. All boots and clothes were made on-board. But it seems a desperate and dangerous place. Even those who survived and graduated to employment were not always any safer. Some of the boys in Llandegfan died in exotic locations, like John Parkin who was “lost at sea with all hands on the Freeman Dennis”, or Charles Dixon who was washed overboard off New Jersey, or James Mort, drowned off Montevideo, Uruguay. Most of them, however, died in accidents on board an old decaying vessel moored off Anglesey and trapped in by the tides. Death appears to have been part of the curriculum.

A home was provided in Liverpool to which they could return between voyages after they had left The Clio. Their work could take them across the world. Life aboard was cramped and brutal and it is hardly surprising that the boys would run like monkeys through the rigging when they could – a taste of freedom, but a dangerous one.

The ship was regarded as a local curiosity. It became a tourist attraction in the same way that Bethlem Hospital (‘Bedlam’) did in London. It was a chance to see the less fortunate and to feel that the exciting modern age in which you lived did its very best for those less fortunate than yourself. Training ships were always short of money and made extra by taking visitors on board for a tour. Visitors could, “Signal the ship from the Pier, for a well manned boat to convey them there and back for a trifling fee.”

Of course, it wasn’t so good that you would choose to go there yourself, far from it. Local parents used it as a threat. The children of Anglesey called it “the naughty children’s ship.” To others, it was a curiosity, an interesting tourist diversion, a floating borstal.

One visitor, Benjamin Goodfellow, went for a visit, well provisioned with Cockles Antibilious Pills to combat the swell. In his journal he comments, “What a fine thing it was to have put so many lads who would otherwise have been lost in evil in the way of earning an honest living for themselves, for on leaving the ship they can get situations with wages of about £2 per month.” And in some ways the solution to a social problem seems very enticing. It appeared to provide an escape route from poverty, a genuine career pathway. But a training ship could be a brutal place, preparing them for a job in which death was commonplace.

It is a place that tells a sad and neglected story. There were a number of training or reformatory ships around the coast. There was The HMS Akbar on Merseyside and The Cornwall at Purfleet. Some training ships were established for prospective Merchant Navy officers. But the ships became unseaworthy and the demand for boys declined as crews became smaller.

The Clio, built as a 22-gun corvette at Sheerness in 1858, was broken up on Bangor beach in 1920.

All that remains now are those five graves in the churchyard at Llandegfan, silent witnesses to incomplete and unfulfilled lives. We should not forget the boys or the unhappy stories which brought them to a decaying ship moored in the Menai Strait.