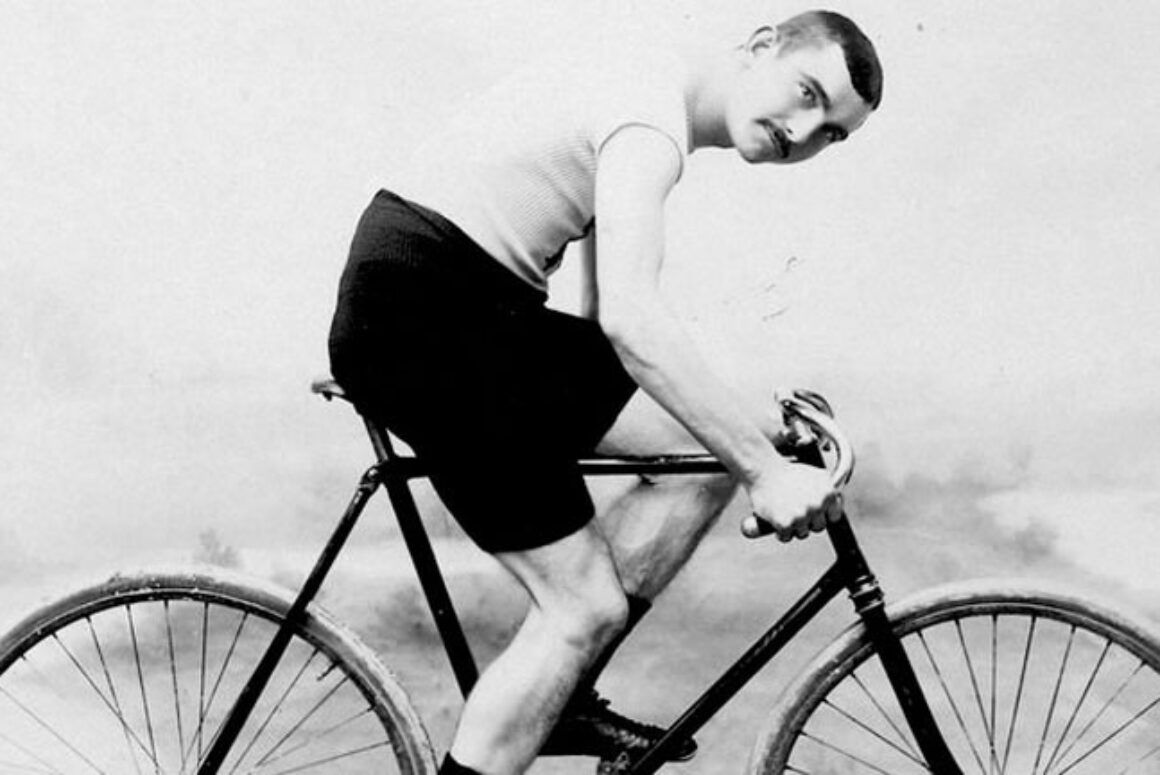

It is extraordinary to think that a small place like the mining village of Aberaman, between Aberdare and Mountain Ash, should produce 4 world class cyclists at the end of the nineteenth century. There were the three Linton brothers – Arthur, Tom and Samuel – and their great rival Jimmy Michael. For a short time they were celebrities, particular Arthur and Jimmy, both of whom became world champions.

It is Arthur who is remembered in Aberdare Cemetery, in Section C plot number E 6/16. beneath a brown marble obelisk on which he is called Lenton.

In memory of Arthur V. Lenton, son of John M. and Sarah Lenton of Aberaman who died July 23rd 1896 aged 28 years.

His was a sad and early death. And a notorious one too, for Arthur Linton is regarded by some as the first victim of performance-enhancing drugs in sport.

The end of the nineteenth century was an exciting time for cycling. The invention of the chain driven safety bicycle transformed the pastime. Riding a penny farthing had been a dare-devil activity, awkward, uncomfortable and dangerous.. But suddenly, with equal-sized wheels and pneumatic tyres it suddenly became accessible to everyone. It became one the great leisure pursuits.

Promotional races were soon organised by cycle manufacturers and serious competitive races soon followed. Soon professional riders were employed by the manufacturers mostly working class boys, anxious to have the chance to race for the large cash prizes. It was a dangerous mix; riders from poor homes prepared to take huge risks in the hope of transforming their finances and manufacturers ready to take risks to increase market share. Cycling, along with boxing and football, was seen as a way in which talent, properly exploited, could liberate an individual and their family from humble circumstances. When the stakes are thus so high, who can condemn those who are prepared to bend the rules and take risks to help their family? Young riders were ready to push themselves to the limit and beyond. Soon it wasn’t just speed that was important. It was endurance. Races became longer and longer and more demanding. The riders were routinely required to over-reach themselves.

Arthur Linton had started racing in the Cynon valley and his successes made him a well-known figure across South Wales. In 1893 he broke all the Welsh cycling records from five to twenty two miles. He was signed as a professional rider for the Gladiator company where he worked under the trainer James “Choppy” Warburton from Lancashire. In 1894 Arthur broke four world records and defeated the French champion Dubois in Paris. He was declared Champion Cyclist of the World. On his return to Aberaman in December of that year he was guest of honour at a public banquet at the Lamb and Flag. The Evening Express in Cardiff praised his ‘pluck under adverse conditions – a courage typical of the Welsh character, and for which the Welsh people will be grateful to him for having displayed’ which I still believe refers to his cycling success, rather than to his bravery at attempting the banquet at the Lamb and Flag.

Choppy Warburton trained no less than three world champions during the 1890s but he was eventually banned from coaching because of persistent rumours that he routinely administeredlarge amounts of drugs. Suspicions were properly aroused when Jimmy Michael from Aberaman collapsed with exhaustion in the middle of a track race. He remounted and set off once more, though now cycling around the track in the opposite direction. Choppy may have trained winners but he stored up huge problems for his riders.

Arthur Linton had his finest and last victory in 1896 when he was racing in the Bordeaux to Paris cycle race, the longest in the professional calendar. It covered 560 kilometres (350 miles) and was more than twice the distance of other single day races. Many of us would think that the race was unreasonably demanding; many of us today might think twice about doing this journey in a car without a reviving overnight stop. Of course Arthur was not only the rider but the mechanic too, carrying with him tools and spare tyres. There was some back-up though, of a sort. The author of Arthur Linton’s obituary in Cyclers’ News said

I saw him at Tours, halfway through the race, at midnight, where he came in with glassy eyes and tottering limbs, and in a high state of nervous excitement. At Orleans at five o’ clock in the morning, Choppy and I looked after a wreck – a corpse as Choppy called him, yet he had sufficient energy, heart, pluck, call it what you will, to enable him to gain 18 minutes on the last 45 miles of hilly road.

We can’t be sure what Choppy gave him but it was almost certainly something a little stronger than encouragement. To recover 18 minutes of lost time in 45 miles, against competitors who themselves were striving their best to win, was remarkable. What he gave him was probably heroin. The other drugs of choice were cocaine and strychnine, though none of them were really performance enhancing. All they did was to dull the pain and help the rider ignore the agony. Whatever it was, it enabled him to set a record time.

So Arthur did win the race. But because he had taken a wrong turn somewhere along the route -not a surprise given the state he was in – he had to share the prize money with the second placed rider, Gaston Rivierre.

Arthur Linton died six weeks later in Aberdare in June 1896. He was 28 years old.

There are those who in these circumstances ascribe his death to the drugs he was given in his desperate attempt to win the prize money. Choppy Warburton was a notorious doper and obviously carried around with him a bulging bag of chemical tricks. This would make Arthur Linton the first athlete to die from the curse of drug use in sport. For some therefore, Arthur has become famous by dying of strychnine or trimethyl poisoning.

However, there are other opinions. Contemporary reports say that he died of typhoid fever. This is possible too. Top level cycling can be especially unhealthy. The body is placed under tremendous strain in an unnatural position. Cyclists are always picking up infections, even today. The big races are constantly disrupted by riders withdrawing through viruses and stomach cramps. It is easy to take in unclean water offered by the side of the road when the rider is constantly trying to rehydrate themselves. Indeed, whilst Arthur’s brother retired from cycling and returned to work in the collieries, his other brother Tom, who also enjoyed a successful racing career, also died of typhoid fever in 1914.

And if you want another interpretation then look at the report in The Herald Tribune. The editorial that reflected on the news of his death says that although the immediate cause of death was indeed typhoid,

The collapse preceding his fatal illness was due to his riding extravagantly geared machines. The tendency to multiply gearing is too much prevalent. No constitution, however strong, can resist the terrible strain thrown upon the heart.

Unnatural distances. Unnatural effort.

You can make your choice. Believe who you will but Arthur, the hero of Aberdare, was dead.

And what of the others in this story?

Choppy Warburton was found dead in a house in Wood Green in London in December 1897. All the money he possessed at the time of his death amounted to three half pennies. Jimmy Michael retired from cycling and became a jockey and horse trainer in America. He died on an Atlantic liner in 1904 from an attack of “delirium tremens” brought on by heavy drinking.

When Arthur Linton died, the local community turned out to honour their sporting hero. His funeral was a huge affair and his cycle, draped in black crepe, was pushed behind the cortege. The tool of his trade and perhaps the instrument of his death, accompanying him to the grave.

He was a young man from a poor community who died whilst seeking glory and wealth when he unexpectedly discovered that he had a talent that others were prepared to use. In this Arthur Linton of Aberaman is not unique.