I saw the boy when I was walking around the grounds of the steelworks. I had only been working in the accounts department for a couple of weeks since I moved to Wales for a fresh start following the divorce. After a morning staring at spreadsheets and crunching figures, I always went for a walk at lunchtime, exploring the works site, looking up at the hills, listening to the birds coming in from the sea. It was therapeutic after the traumatic time I had gone through recently and good to get some fresh air and stretch my legs.

I had read in the works newsletter about some kind of ceremony which was taking place today. It was going to be in a grassy area on the edge of the works where there is a monument associated with the mine which used to be there over a century ago. I thought that I would find out what it was all about. When I got there, I could see a structure in the centre with a shovel and other tools embedded in it. It was on a low plinth, so I sat down there to eat my lunch. I could feel the warmth of the sun on my face, relaxing me.

I heard a cough and looked round noticing that there was a boy sitting round the other side of the structure. He looked at me and gave a small wave with his hand.

I smiled and waved back, ‘Hi, there, I’m Mark, I work in accounts.’

He nodded, ‘I’m Ewan.’

He was oddly dressed, a bit like a goth with matted unkempt hair and black clothes showing holes in the knees. His face was pale with a smudge on one cheek. He rubbed his tired looking eyes and I noticed that his fingers were engrained with dirt.

‘Work experience?’ I suggested, thinking that he couldn’t be working in the offices dressed like that and was too young for the steelworks, maybe he was helping the groundsmen, that would explain his muddy face and hands. Then it came to me, he was here for the ceremony, dressed as a collier boy, maybe he was going to recite a poem or read something.

‘Are you going to tell a story about the old mine?’ I asked, ‘You really look the part. I like your clothes; how did you get them?’

‘My mam sorts out my clothes for me, always does. I can tell you a story about the mine right enough.’

The sun went behind a cloud and I suddenly shivered, ‘Cold out here.’

‘Not as cold as where I’ve been,’ Ewan said, ‘I’ll tell you what happened. It started a couple of months ago. We could hear the dogs howling at night. One of my Da’s mates, Rhodri, said they were the ‘Red dogs of Morfa’ and had been seen before when there had been explosions twenty to thirty years ago in the mine. Of course, Gwynfor and I laughed at that, superstitious nonsense. We went out one evening to see if we could spot them and prove Rhodri wrong. Well, we could see some dogs on the top of the hill across the valley,’ Ewan waved his hand in the direction of the hills, ‘About six of them, howling with their heads up like wolves. The moonlight was shining on them and I could swear that they were a reddish colour. I didn’t know anyone with a dog like that. Gwynfor and I were rooted to the spot and I could feel the hairs going up on the back of my neck. Then they all raced together in a pack down the hill towards the valley. We got moving fast then and ran back home as if the dogs were already at our heels.’

Ewan turned towards me eager to tell his story, his eyes shining, ‘That wasn’t the only strange thing, you see Gwynfor and I both went down the mines like my Da and most of the men from around here. We were working with the horses, pulling the trams. It’s smelly down there with droppings and the damp. Gwynfor said to me, “Can you smell that? It’s like flowers or perfume.” It was such a sweet, sickly smell, like when you change the flowers in the churchyard and tip out the old water. “Death flowers,” he hissed, “Bad luck, my Da told me about them.”

‘And,’ Ewan continued with emphasis, “There were the noises. I swear one day I heard a rumbling noise, like earth falling and heard a voice calling “Help.” I hurried round the next bend in the corridor, there was no one there, but I saw lights near the top of the wall flickering like candles, but as I got nearer, they disappeared. Gwynfor said that he had seen these ‘corpse candles’ before. His friend, Dafydd who worked on a different seam had seen a ghostly mine with white horses pulling a coal tram. Everyone was spooked by this, and do you know some people didn’t turn up for work. Me and Da couldn’t miss a day though, I’ve four brothers and two sisters. We need the money to put food on the table.’

Ewan looked at me, I nodded in encouragement. He was doing really well. I was impressed with how he had learnt the story off by heart and managed to put such a lot of feeling into it.

‘But, do you really believe in the supernatural events yourself? What do you think really caused them?’

‘Well, some people say the noises are from when the sea is rough. You see the workings go right out near the sea. The seagulls may sound like people calling for help I suppose. Maybe the dogs are just strays. But it doesn’t explain the scent of roses, the lights and the ghostly miner and horses, does I t?’

He looked at me intently, I was impressed with him sticking so well to his character.

‘But let me finish my story,’ he insisted, ‘These things I’ve told you about were warnings, I just know it. When I went to work this morning, it was the same at usual. Gwynfor and me had just stopped for our dinner when it happened. The explosion must have knocked me out. When I came round it was pitch black and I was covered in dust; I felt dizzy and sick. You see there’s something called afterdamp, which gets into your chest and can kill you. I called out for help and was relieved when I saw Gwynfor leaning over me.

“Ewan, get up, follow me. We must get out of here.”

‘He pulled me to my feet and we stumbled towards where we thought the way out was. Then we realised there were bodies of miners in front of us. We climbed over them putting our handkerchiefs over our faces because the smell of afterdamp was so bad. Sometimes we had to climb through small spaces because the roof had partially collapsed. Eventually we could see a light in the distance and hear voices through a crack in the rubble. Gwynfor started scrabbling over the debris towards the light and pushed his hand through a small hole.

‘We could hear one of the men shouting, “Over here lads, there’s someone alive in there.”

“It’s all right boyo, we’ll get you out,” he said and we could hear them pulling stones away and gradually the hole got big enough for us to get out. I tell you, seeing the sky and breathing fresh air was like a miracle.’

I clapped my hands and smiled, ‘You tell a fine tale. Would you like something to eat? I’ve got one chocolate biscuit left.’

‘No, Mam will have a hot drink and bara brith for me when I get home.’

Just then, I heard the clang of a gate and turned to see a group of people walking across the grass towards me.

They were a mixed group but all with serious expressions on their faces. Men from the works in overalls, some people smartly dressed, one woman seemed to be wearing some sort of chain of office and leading them was a man wearing a dog collar. They all stood round the structure where I had been sitting a minute before and I tried to merge in with the group.

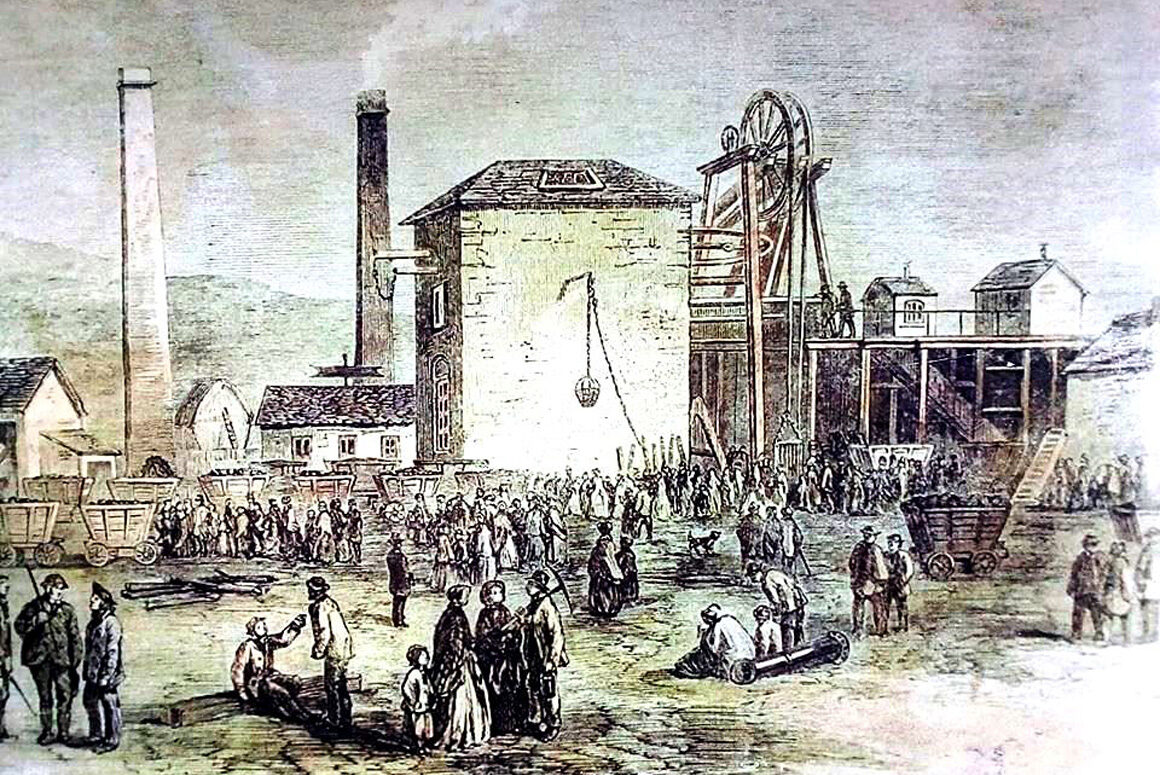

Everyone hushed and the minister spoke, ‘We are here today to remember those miners who died during six explosions between 1849 and 1890 at Morfa Colliery. The worst explosion was on 10th March 1890 when eighty-seven men died, exactly one hundred and thirty-two years ago to this day.’

I peeped round to see if I could spot Ewan, probably waiting to tell his story, but he had disappeared, it was odd because there was no one in the field except the people round the memorial and I hadn’t seen anyone going out through the gate.

The minister continued, ‘This memorial sits almost exactly over the entrance to the old mine shaft where there still lie fifteen miners who sadly lost their lives in the explosion.

‘We are lucky to have with us today, Mrs Emily Jones, whose great great uncle, Ewan, died in the disaster. He managed to get out but died later of the fumes he had inhaled during his escape.’

‘Let us keep two minutes silence in remembrance of all those who died.’