You need to go some to earn the epithet ‘infamous’. George Jeffreys, or 1st Baron Jeffreys as he became, was a Welsh judge who was, well, infamous. He’s also known to history as ‘the Hanging Judge’. In his determination to enforce the royal will, he displayed a ruthlessness that cast adrift worthy attributes such as fairness, even-handedness and mercy.

Feature image: George Jeffreys, 1st Baron Jeffreys of Wem (Source – Public Domain)

Jeffreys was born at Acton Hall, near Wrexham, the sixth son of John and Margaret Jeffreys. The legal profession, and law enforcement, ran in the family. His grandfather, John (died 1622), had been a Chief Justice (Anglesey), and the catalyst for the family’s prosperity, whilst his father had been High Sheriff of Denbighshire. Nothing remains of the Jeffreys’ ancestral seat, which sadly was demolished in the 1950s.

George was called to the bar in 1668 (during the reign of the Restoration monarch, Charles II) and rose rapidly. In 1671, he became common serjeant of the City of London. Leaning towards Puritanism, Jeffreys showed a willingness to compromise his principles to gain favour and advantage. He began intriguing at court (the royal court that is) and became solicitor to the Duke of York (the Duke, the future James II, was the younger brother of Charles II and would play a key role in Jeffreys’ acquisition of infamy).

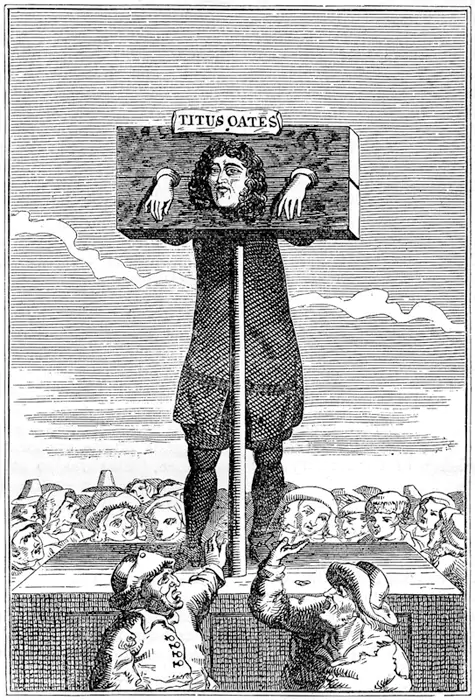

Jeffreys was knighted in 1677 and became recorder of London in 1678. Everything was going swimmingly. His reputation grew as he participated in the ‘Popish Plot’ prosecutions (1678-81) whereby anti-Catholic hysteria was whipped up by one Titus Oates, a perjurer who denounced innocent men for their part in a supposed Catholic plot to dispose of the king.

Jeffreys was married twice, the second time, in 1679, to Anne, the widow of Sir John Jones of Fonmon Castle, Glamorgan. It’s said that Jeffreys met his match with Anne, who had a formidable temper, and may have been the one person he was afraid of. It’s reassuring that the ‘Hanging Judge’ was universally feared but couldn’t wear the trousers in his own household. Riding the crest of a wave career-wise though, Jeffreys became chief justice of Chester, king’s serjeant (1680), a baronet (1681) and chief justice of the King’s Bench (1683).

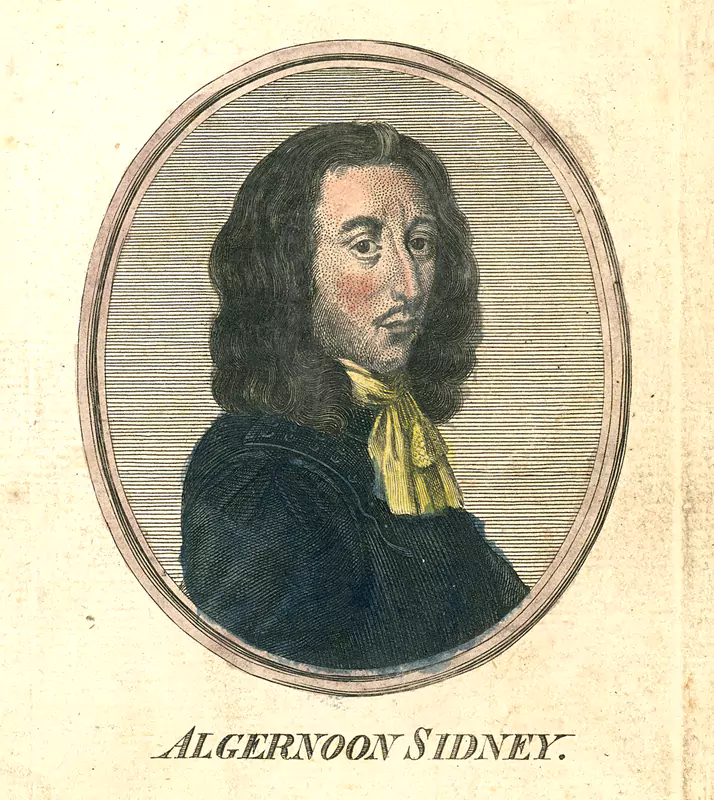

Jeffreys’ unemotional and ruthless resort to judicial murder was illustrated by the case of Algernon Sydney (1623-83), who was executed in December 1683, in the fallout from the Rye House Plot, a botched attempt to assassinate both the king and his brother. Sydney, a politician-philosopher, was charged with plotting against Charles II, as much for his revolutionary writing as anything, and was decapitated with the axe at Tower Hill. It was a typical example of Jeffreys use of the state trial as a tool for supporting, and ingratiating himself with, the monarchy.

It was all change in February 1685, when Charles II died, and his sibling, James, became King James II. One of James’ first moves was to elevate Jeffreys, a trusted servant, to the peerage. Amongst his first trials on James’ behalf were those of Titus Oates (1649-1705) and Richard Baxter (1615-91). Oates was lucky as Jeffrey’s couldn’t impose the death penalty for perjury, so he was imprisoned, whipped and pilloried. Oates was one of the few who slipped through Jeffreys’ clutches, and was pardoned in the next reign, living until 1705. Baxter’s ‘crime’ was allegedly libelling the church, for which he was fined and dumped in prison for 18 months, even though he was approaching 70.

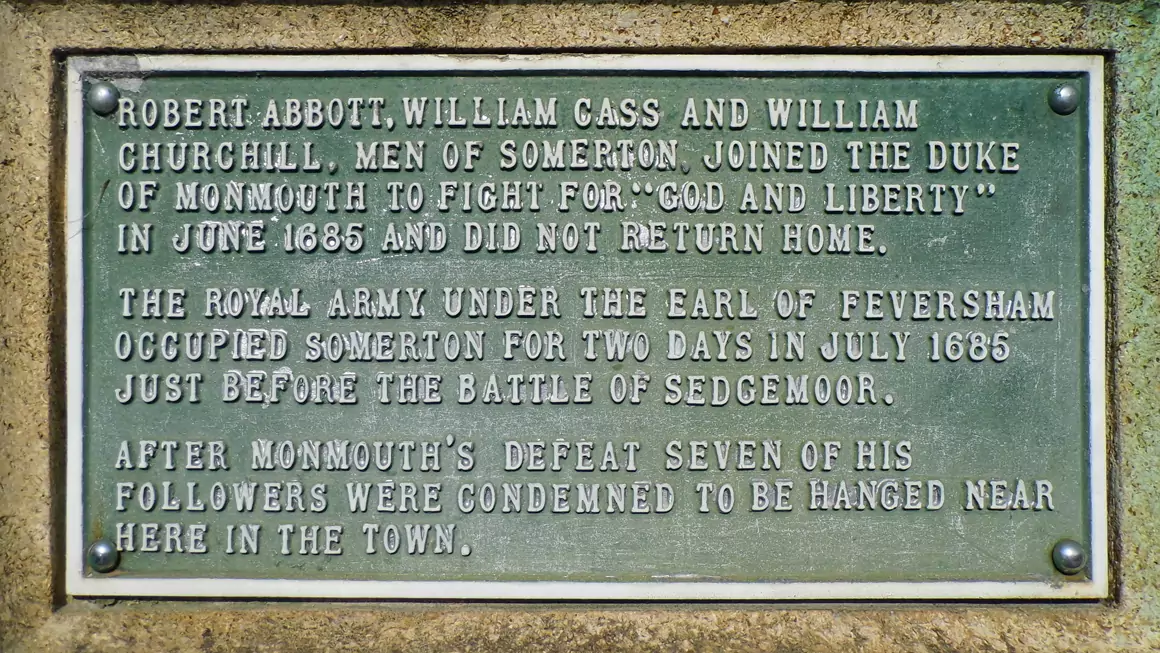

Jeffreys’ notoriety peaked, however, when he was sent to England’s west country to try the participants of the Monmouth Rebellion (1685). Many had become concerned about a lurch towards Catholicism under James II, who married his second wife, Mary of Modena, in a Catholic ceremony, in 1673. James Scott, Duke of Monmouth, was the illegitimate son of Charles II, but was crucially a Protestant, ultimately leading his eponymous rebellion to defeat at the Battle of Sedgemoor (July 1685).

It was the aftermath that cemented Jeffreys’ reputation as a vicious adjudicator as he meted out ‘justice’ to the participants in the so-called ‘Pitchfork Rebellion’. Hundreds of simple country folk were executed (some 320), transported (800), whipped and fined during the ‘Bloody Assize’. One of the places Jeffreys held court was Dorchester, where you can visit his lodgings, and, around the corner, his court room, ‘the Oak Room, which was once part of a hotel, but is now a self-contained tea room. It seems incongruous to supp tea where the ‘Hanging Judge’ went about his business.

Jeffreys became Lord Chancellor from September 1685, a position he held until James II himself fell from grace in the ‘Glorious Revolution’ of 1688, when he was deposed by the Protestant dual-monarchs, William and Mary. Jeffreys’ backed all James’ measures as president of the newly-revived Court of High Commission but did break ranks over the trial of the seven bishops (June 1688), advising James not to prosecute them for their opposition to his religious changes, but the king persevered, and was severely embarrassed when the men were acquitted. This case does suggest there was another, more considered side to Jeffreys,that has perhaps been largely overlooked.

In fact, if you burrow deeper into the legend of the ‘Hanging Judge’, you find that he may have been more nuanced than he’s been given credit for. He wasn’t perhaps the out-and-out ‘toady’ of the crown that has been suggested and didn’t always favour doling out punishment or doing everything necessary to endear himself to the reigning monarch. He held sensible views on witchcraft, for example, and was too principled to convert to Catholicism himself.

Although he may not have been a 100% full-blown servant to James II, the deposition of the Catholic-leaning monarch would still act as Jeffreys’ undoing. Jeffreys tried to follow his master’s example and flee the country for his own safety, but was held at Wapping, disguised as a sailor (clearly his disguise wasn’t good enough).

Jeffreys then faced the same kind of punishment he’d meted out so many times himself, being dumped in the Tower, awaiting the monarchs’ pleasure (William & Mary). The story is that he was placed in the Tower for his own safety as the mob was after his blood. He’d no doubt made many enemies over the years.

Jeffreys was lucky as he never faced execution, unlike so many of his victims. He died whilst in captivity, possibly of kidney disease, in April 1689. He was aged 43. Apparently, whilst in the Tower, Jeffreys reflected on his ‘Bloody Assize’, ruefully commenting to the Tower’s Chaplain that, ‘I was not half bloody enough for him who sent me thither.’

Words: Stephen Roberts

References:

Chambers Biographical Dictionary (1974)

A Dictionary of British History (Ed. JP Kenyon, 1981)

Quotations in History (A & V Palmer, 1976)