![]()

It was said that all Robert Webster’s problems started when Mary hit him over the head with an iron. But I am not so sure; to be honest, I think they started before that. You see, his domestic arrangements had always been rather too complicated. I do wonder if, as he sat his pot of thin beer in the Colliers Arms in Efail Fach on that life-changing Saturday night in October 1868, he found a moment to reflect upon the complete mess that his life had become.

He first came to notice in October 1867, when he appeared in court charged with ‘Neglecting to maintain a family’. He was merely a simple labourer in his late forties, who worked maintaining the roads, and it appears he was not using his earnings to support his family.

His defence was quite straightforward. He told the court that he had always been diligent in supporting his family until his wife, Lucy, ‘took another man into the house’. This was a 21 year old collier, William Whitelock, who was significantly younger than Lucy and was possibly in a relationship with their daughter, Mary Jane Webster. To think that he might have been in a relationship with Lucy is just too complicated, to be honest. But whatever the circumstances, Webster was asked to leave the family home, and as a result he refused to pay maintenance. Lucy, who may have been his wife but might not have been, since no marriage was recorded anywhere, could have thrown him out because he was already in a relationship with his landlady Mary Morris, but we will come on to that shortly.

I hope you are keeping up.

The court was not in a position to offer relationship counselling. All they could offer was to drop the charges if he paid the arrears and costs. I suspect that he wasn’t too happy.

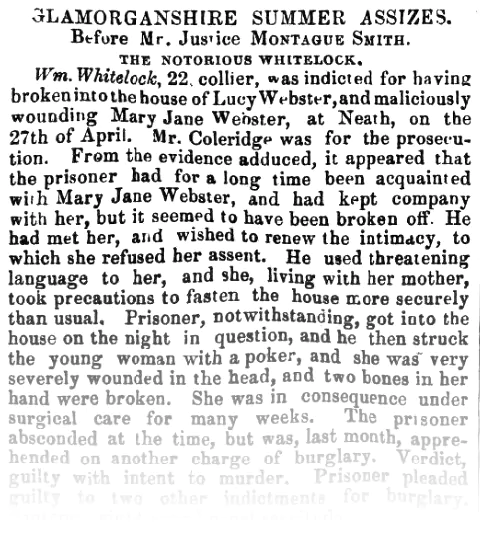

In August 1868 these domestic challenges emerged once again. By now, William was known as ‘The Notorious Whitelock’ and had finally been arrested for a string of burglaries. When he was eventually brought to court in August, his most disturbing offence occurred when he broke into the home of Lucy Webster in Neath in April and wounded her daughter Mary Jane ‘with intent to do grievous bodily harm to her’. Whitelock had for a long time ‘been acquainted with Mary Jane Webster, and had kept company with her, but it seemed to have been broken off. He wished to renew the intimacy, to which she refused her assent’.

At some point he had been thrown out and now broke into the house to attack Mary Jane with a poker. ‘He severely injured her about the head, and broke two of the bones of her hand’ as she protected her baby, who was in bed with her. He admitted the attack, ‘I did strike her, and it served her right, if you knew so much about her as I do’. Was it his child? We don’t know, but it is possible. Whitelock was found guilty of assault with intent to murder and was sent to gaol for eight years.

Whilst all this was going on, Robert Webster had started another relationship but as the year wore on it didn’t seem to be working out very well. He had moved in as a lodger with Mary Morris and her husband Morris Morris and before too long, as was reported at Webster’s trial, the three of them were ‘living together in a state of the greatest depravity’.

It had probably started when Morris was working away from home. He too worked on maintaining the roads. Perhaps he offered a room to his workmate, Webster. We don’t know. Mary herself took in laundry, washing and ironing. Morris was very clear that he did not maintain her, which may have encouraged her sense of independence.

Theirs certainly wasn’t the best ordered home. Morris was reasonably sure that he was married to Mary, because she had said her husband, Edward Hughes, had died and any suggestion that he was still alive was just a rumour subsequently circulated by Webster to create some mischief. As you might anticipate, things were a little tense at times, and at the beginning of 1868, Mary had fractured Webster’s skull with a flat iron ‘which did him considerable injury and from that time, his feeling seemed to have changed towards her’. How strange.

In October, though, everything between them appeared quite amicable. But it was clear that Webster had something on his mind. In the morning he had visited Hopkin Jones’ Ironmongers in Neath and borrowed a pruning hook for twopence, something he might need for his work on the roads, asking ‘whether it would do to cut a person’s head off’. Casual question. We’ve all asked that question at some time or other. Haven’t we?

They went out together to the Colliers Arms in Efail Fach, Pontrhydyfen. Webster kindly arranged for the beer to be warmed for Mary as she requested, and Webster’s son bought a drink for Morris, too. They all went home for supper, after which Morris fell asleep. Webster and Mary then went out again to Jenkins the Grocer in order to redeem a shawl that Mary had pledged some months before – the shop offered a simple a pawn service to customers when necessary. Webster asked Mrs Jenkins to transfer the debt of 14 shillings for the shawl to his existing bill at the shop. As they left, Mrs Jenkins noticed that he had the pruning hook, wrapped in paper, under his arm.

According to Webster, as they walked home, despite handing the shawl over to Mary, they argued once again, as they had done so many times in recent months. He claimed that she said You old devil, now I’ve got my shawl I won’t wash for you, or do for you, any more. She then hit him. In his own words, ‘I chopped her with the hook’ and then he shouted at her, ‘You shall never hit me again!’ When he realised what he had done, ‘I rose the dear lamb’s head’ from the ground, kissed her and then surrendered himself to the police.

The examination of Mary’s body by the surgeon George Ryding from Neath however, showed that he had not told the full story.

‘There was a large stab on the jaw. There was a zigzag wound in the throat. The jaw bone was laid open. An instrument like the one produced would cause such wounds as those described. The wounds were inflicted before death’.

The wounds were nasty enough, but did not cause her death, which was caused by strangulation. ‘Very great violence must have been used on the throat’. He must have grabbed her and squeezed very hard.

The hook, still partially wrapped in paper, and the shawl, were both soon recovered and Webster confessed to the crime immediately, ‘I have murdered poor little Polly, and she’s lying dead in the road’, though his statements were long and rambling. He told the constable ‘I was born to be hung and shall die like a lamb’ and then he went on to make a strange request.

‘I have one favour to ask you, and that is, I want to see a child who saved her life nine months ago. He happened to come on two occasions where we were in the hill walking and saved me from murdering her’.

The only question was whether he was guilty of murder or manslaughter.

In his trial at the County Assizes in Cardiff, it was the intervention of Judge Baron Bramwell that saved him. There wasn’t any doubt that he had done it, that much was obvious. But what wasn’t clear was whether he intended to kill her. That was the key, because, if there was intention, it would lead to conviction for murder and an inevitable execution.

Webster hadn’t helped himself at all. Obtaining the hook wasn’t wise and neither was his admission that he had planned to kill her previously. As Bramwell, said

‘That was a remarkable thing, and if (the jury) should be of opinion that the prisoner had some homicidal propensity against that woman in particular, which he gratified upon the occasion referred to, and they attributed that fatal blow, not to the heat of blood, but to an evil disposition towards her, they must find a verdict of murder and not one of manslaughter’.

In fact, telling Mary that ‘she would never hit him again’ could suggest that he really did intend to kill her. And he couldn’t use insanity as his defence, because he knew what he had done and he admitted it. But then, you see, when he borrowed the hook, did he really say ‘cut a person’s head off’ or did he say ‘cut a person’s hedge off?’ An important difference. How could anyone really know?

One significant element of the story was not revealed in the court case, but had been raised earlier at the inquest. It was perhaps just as well for Webster that no one brought it up. Morris Morris testified at the inquest that Webster had tried to kill Mary in May 1868. He had attacked her with a hammer, cutting open her head. He testified that She bled like an ox, and screamed out. I ran into the house, and prevented him giving her another blow, or he would have killed her. He ran out of the house. That could have made a big difference.

But as it was, no one else saw what happened when he attacked Mary. Webster said that she had hit him and he had responded. Remember, she had hit him before and caused a serious injury. Webster obviously over-reacted on this occasion, but Mary had previous, as they say, and his evidence suggested there had been provocation. It was, the judge suggested, ‘a crime committed in the heat of blood caused by a blow he received’. If he had planned to kill her, surely he would have unwrapped the hook before he hit her with it. He must therefore have acted impulsively.

Their unusual domestic arrangements had created a context of immorality and chaos for which Mary, Morris and Robert were all equally responsible. Disaster was inevitable. According to the police, ‘it was a mere lottery as to which would be killed first’. In such depraved atmosphere, everyone was guilty, even the poor woman who was innocent. She had brought such a fate upon herself as the result of her behaviour. What could she expect? The whole story was a sad but entertaining insight into the immorality of the poor. Let this be a warning to you. This is what happens if you don’t follow the rules.

The jury retired for only seven minutes and returned a verdict of guilty of manslaughter. Bramwell agreed with their verdict and then sentenced Webster to 20 years’ penal servitude.

And what of poor Mary Morris?

‘The body of the unfortunate woman was buried at Llantwit cemetery, the funeral itself being a fitting ending to the depraved career of such a being, two or three men only, in labourer’s attire, walking smartly after the corpse, as if to hide as quickly as possible from the world the last remains of the fearful tragedy’.