![]()

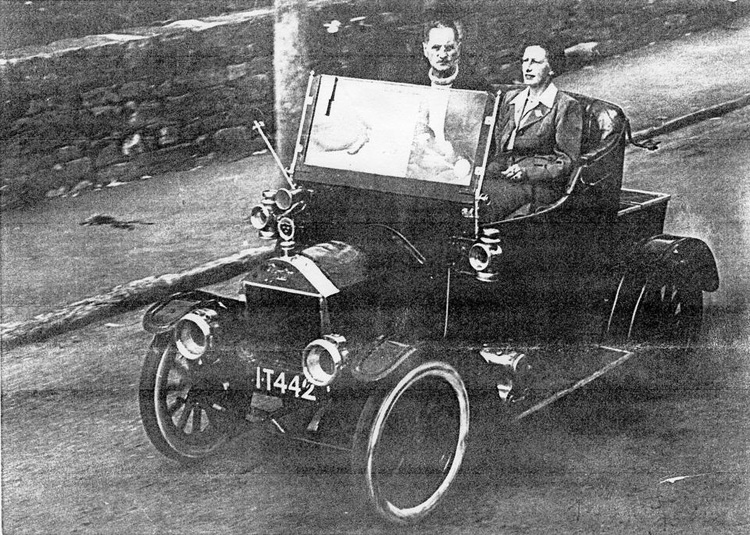

The thing is, in 1909 a car was a new enthusiasm, reaching out slowly but steadily to take over the quiet roads of Wales, a new, exciting but dangerous toy.

The roads were still nineteenth century roads that had been designed for horses, not machines. But of course drivers knew better, confident in their own abilities, which they considered way beyond those of ordinary mortals. Because they possessed the exceptional powers needed to drive a car, they saw themselves as above criticism. As we are all know, that feeling persists amongst some road users even today.

In Llandudno Junction there was an early example of the tiresome concept of the boy racer, when Mr Margerison of Preston, and W. G. Nicholson, the chauffeur to Mr Allan, of Prestwich, decided to race each other on Good Friday afternoon, when there was considerable vehicular and other traffic on the road between Llandudno Junction Station and the railway crossing.

PC Davies, who was on duty at the level crossing, saw two cars racing towards him at excessive speed, side by side, attempting to overtake each other. A witness estimated their speed at over twenty-five miles per hour.

The defence council dismissed such scurrilous claims the road was clear and straight, he said. Nicholson overtook Margerison (eventually) at no more than eighteen mph, though since he had no speedometer, this was no more reliable than the witness’s estimation. There could be no proof of the speed achieved and so the case was dismissed, though the magistrate did express some sympathy for PC Davies, commenting that now the population was divided into two classes—one class comprising of those who rode in cars and the other of people ready to be run-over.

It is clear that the concept of speed was a difficult one, for everything in the world had always previously happened at a much slower pace. Miss Whitting, for example, was driving from Penderyn to meet the Pontvpool train at Hirwain. She lost control of the car at a bend in the road near the Great Western Railway, careered through the railings on to the G W.R. platform where the car rolled over. Fortunately it did not fall down on to the tracks in front of the train and she was relatively unscathed.

In Cowbridge in May 1909, Tudor ap John from Trealaw had to face a charge of reckless driving. The complaint was brought by Robert Trimlett, chauffeur to Dr. Skyrme from Hastings. When he was driving from Porthcawl to Cardiff, Trimlett had overtaken a slower moving vehicle driven by ap John. When, further along the road he saw a vehicle approaching in the opposite direction, he pulled into the left-hand side

We all know that there are some people who don’t like being overtaken – and ap John was clearly one of them. He came up quickly behind Trimlett and overtook at speed without the faintest warning, almost scraping his car. This was a shocking moment.

Yes, Mr Trimlett. We have all been there, but perhaps I have an advantage. I do much of my driving in Swansea so I am used to this sort of thing.

As far as Dr Skyrme was concerned a smash was inevitable. Any man who acted like that could be nothing but a madman. This made the defence counsel a bit shirty. What right do you have to say such a thing, he asked? Are you an experienced motorist? ‘No I am not, but a man who would do such a thing has not the proper control of himself.’ Mrs Skyrme agreed.

Tudor’s defence was based upon the different opinions about what constituted reckless driving. He had a clear view of the road and anyway he had passengers, three ladies and three children, and he wouldn’t have put them at risk. When he overtook, he sounded his horn, well after changing gear, and his car was actually passing Trimlett when he saw the car coming from Cowbridge. He had to decide without any hesitation whether he would drop behind the car or accelerate He was quite clear of Trimlett before the third car was close to them. He denied emphatically that he ran the slightest risk in what he did, for he would not attempt anything involving danger.

Tudor confirmed that he was seventeen years old and had held a license as a motor driver for a little over a month. He learnt the way to drive at Cardiff, which has in my view a mixed reputation as a centre of driving excellence. When asked ‘How far were the wheels of your car from the wings of Dr Skyrme’s when you went past?’ he replied ‘I didn’t look behind. A motorist should not do so when driving.’ Which rather confirms my point, I think.

His father Henry John Ap John, who was also in the car, gave supportive evidence. There were, in fact, two horns on the vehicle; he blew one and Tudor the other before they overtook. When the magistrate commented that he was trusting himself with an inexperienced driver and Henry was affronted.

‘My son has been concerned in driving since he was ten years old.’

‘Driving motor cars?’

‘No. Horses. And he has a bicycle as well.’

His mother then added that she did not think the slightest danger was involved in what her son had done otherwise she would have screamed.

You do wonder whether either of these interventions by his parents were helpful. After a brief retirement, the Bench imposed a fine of £1 and £1 4s. costs, and his licence was endorsed.

But sadly, driving wasn’t just about exasperating naughtiness. Mr Tombs, a Fishguard solicitor, was being driven through Whitland, when Mary Rees, the seven-year-old daughter of a railway signalman, ran across the street and was knocked down. They said the car was so silent she hadn’t heard it. She broke her left arm and sustained internal injuries. None of the wheels passed over her body. The chauffeur was praised for stopping so quickly, stopping the car within its own length. Poor Mary died later in the evening but at least the chauffeur was exonerated.