![]()

You can tell that something was going on when you see this advertisement in the Cardiff press in March 1896

Upright Iron Grand – Gentleman leaving for Klondike Goldfields must Sell most superb Drawing-room Piano in lovely walnut especially suited for classical music; new this season.

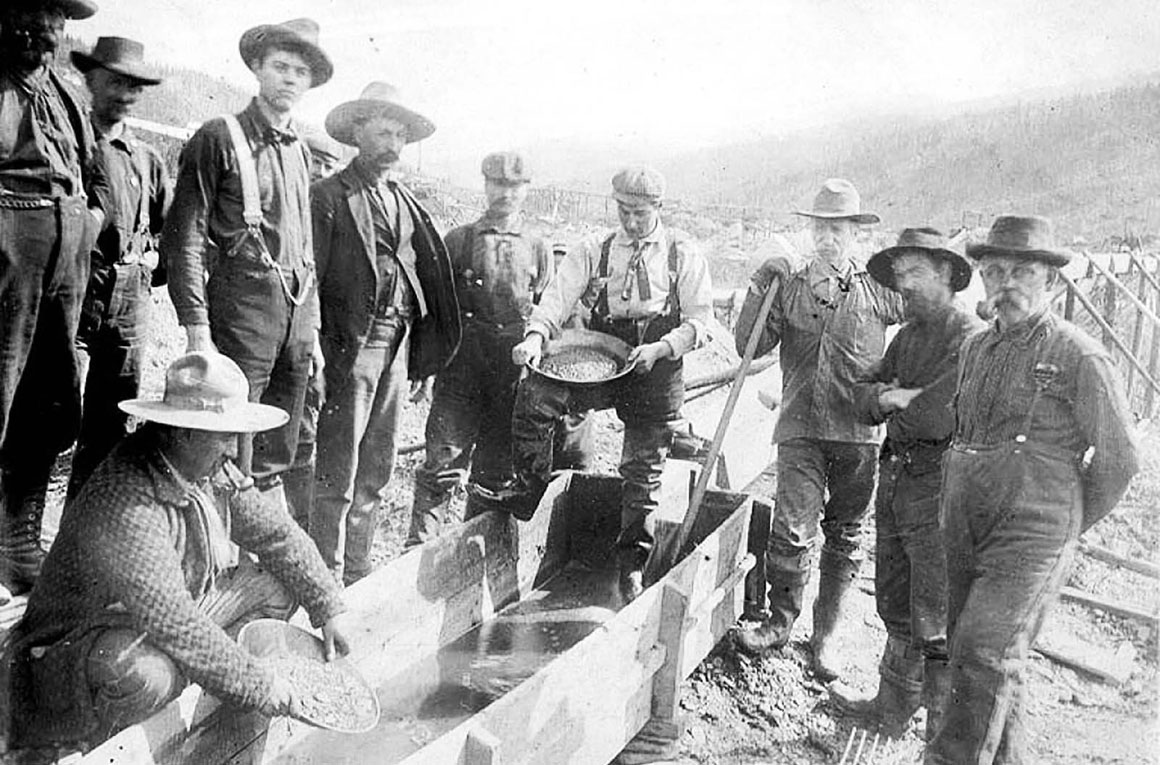

Soon the newspapers were full of news from the Klondike, a fascinating, frozen waste where it was believed that fortunes could be made, where they believed that gold dust was the common currency. This was the legendary Klondike Gold Rush that briefly seized the imagination of the world. The reality of course was completely different. The most valuable commodity was not gold dust; it was food.

Once the news was out, over 100,000 prospectors rushed to the Klondike region of Yukon, in north-western Canada, between 1896 and 1899 from across the world. Though only about a third of them ever arrived. A handful became rich; most did not.

Each one of them was required by the Canadian Government to take with them food sufficient for one year, since there were not sufficient natural resources to support them. This meant that they had to carry equipment and supplies across difficult frozen terrain in stages. The cost of renting pack animals was enormous. One of the routes into the Klondike became known as Dead Horse Trail. If you want to dig for gold at Klondyke, said Cardiff’s Weekly News, you must take plenty of food with you, or else be armed with an infinity of bank-notes.

The South Wales Daily News in 1897 interviewed an enterprising gentlewoman about her plans:

I go to Klondike to find my fortune not in the frozen earth, but in the belts and pockets of those who are successful and desirous of the comforts and luxuries they have left behind in civilisation, and which I may be able to obtain for them.

In one important respect she was right. There was little money to be made prospecting, but there was plenty to be made from servicing their dreams, whatever shape they might take. This is emphasised in December 1897 by W. H. Goss, from Cardiff, who sent The Weekly News a letter he had received from his brother who had gone to the Yukon. Stay away, the brother had said, unless you have money to throw away. There are hundreds of men up there, and most of them wish they were back home. The advice he gave was that there was more money to be made in packing – carrying the supplies for the dreaming prospectors. The packing last spring was as high as 50 cents per pound, and that is for about six miles, and then you go back and get another load.

At the confluence of the Klondike and Yukon rivers, Dawson City grew rapidly and became central to the whole goldrush, servicing every kind of need. It was dangerous place, lawless, isolated, unsanitary and wildly expensive. Built completely from wood, the town was frequently ravaged by fires. There were traders, there was drink, and there was entertainment. There was the Monte Carlo, which operated as a combined saloon, gambling hall, theatre, dance hall and restaurant. It was not the only establishment to offer theatrical entertainment. To the north of this was The Horseshoe Saloon, where the Oatley Sisters operated a dance hall and theatre where they regularly performed, believing they were in London or Paris or New York – and not in the Yukon.

During the day, when things were quieter, these places held auctions to sell off equipment from disillusioned prospectors. They also featured special events such as benefit concerts, masquerade balls and boxing matches. They were open around the clock. You could drink play poker for a while, watch the floor show in the evening, and if you had the stamina, stay for the dancing that continued to the early hours of the morning whilst you tried to forget how far away you were from anywhere else.

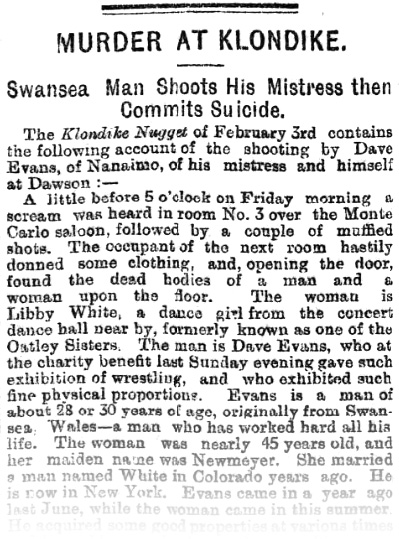

At its peak, Dawson supported two newspapers and it was in one of them, the Klondike Nugget, that the Dave Evans story was first reported in May 1899.

KLONDIKE MURDER. SWANSEA MAN SHOOTS HIS MISTRESS. SUICIDE OF THE MURDERER.

A little before 5 o’clock on Friday morning, a scream was heard in room No. 3 over the Monte Carlo saloon, followed by a couple of muffled shots. The occupant of the next room hastily donned some clothing and, opening the door, found the dead bodies of a man and a woman upon the floor.

The woman was Libby White, a dance girl from the Horseshoe Saloon, who occasionally appeared as a member of the popular attraction, the Oatley Sisters. She was almost 45 years old. She had been born Elizabeth Newmeyer and had married a man named White in Colorado some years earlier. And whilst she was entertaining in the Klondike he was by now living in New York.

The man was Dave Evans from Swansea, who had appeared at a charity benefit a few days before in an exhibition of wrestling, showing such fine physical proportions. He was in his late twenties a man who had worked as a manual labourer all his life and who had arrived in the Yukon in pursuit of an impossible dream, like so many others.

He had been in the Klondike for about nine months, whilst Libby had arrived a few months after him. Evans had achieved some limited success but he had spent lavishly, in a place where the normal rules of common sense and economics appeared to have been suspended. The two of them had been together for a couple of months and had jointly acquired speculative prospecting rights on strips of land along a number of local rivers and creeks that they could exploit themselves or sell on to others. Dave was particularly interested in one claim they’d staked on Bear Creek which they had decided to work together. This was the one, they were sure of it.

However, all was not well between them.

The woman’s promiscuous tendencies occasioned several severe quarrels during the two months they have been together. By the advice of friends he decided to try and break with the woman.

Now one of Libby’s more persistent admirers was in the town, and she had decided to spend some time with him. She made a proposition to Evans which he strongly objected to. While Libby was away from their room, Evans commented casually to a friend, Eddy Dolan, in the Monte Carlo that he had not yet returned a revolver he had borrowed a few weeks ago for a trip up to Bear Creek. Eddy advised him to return it but Evans laughed off the suggestion.

Later Eddy heard him leave his room and thought he had decided to return the revolver but he seems to have met Libby on the stairs, and they returned to their room almost immediately, where a quarrel could be easily heard. Suddenly Libby screamed and there was a shot, and all was silent. Then another shot, and then silence once more.

Dolan knocked on the partition wall, and asked what the matter was. No answer. He went next door.

The woman was lying, dressed, on her face, with her head in the water bucket, and with blood oozing from a wound in the back of her head. The man was sitting upright on the floor in a cramped position, with his cross feet against the washstand and his head thrown backward over the bed. A wound just back of the right and left temples showed how death had occurred.

There was little here to trouble the Canadian Mounted Police.

It was a case of murder and suicide, and showed that it would be unnecessary to secure a coroner’s jury to demonstrate it, so that one was dispensed with.

It was also in 1899 that gold was discovered near Nome in Alaska, and suddenly the Klondike Gold Rush ended as quickly as it had started, when prospectors took their dreams further north.

That is what the Klondyke had always been – a dream which had delivered for hardly anyone at all and which was replaced by a new illusion in Alaska, where things would obviously be better.

Sadly, Dave Evans’ dreams ended forever, in a shabby bedroom far from home.