![]()

As the Shropshire Union Canal Society busily restore the Montgomery canal and close the Shropshire Gap, they are not only bringing the waterway back to life, but also uncovering long forgotten local stories, for as a digger shaped the canal channel at Crickheath Tramway Wharf, it came across ironwork from a narrowboat deep in the earth. All the woodwork had long since rotted away but the iron skeleton remained bent but not broken.

It turns out that the sunken vessel was, almost certainly, the Usk, a ‘Narrer-narrer’, slang for narrow-narrowboat, and she is said to be haunted by the boatman who skippered her and was killed in an accident nearly one hundred and fifty years ago.

However, the story doesn’t start at Crickheath on the Montgomery canal but at Hadley Park Lock on the Trench Arm of the Shrewsbury and Newport canal in what is now, Telford. (The canal was abandoned many years ago.) The Trench arm built as a small coal canal with the lock being only 6’ 7” (2 metres) wide, so could only take tub boats or ‘narrer-narrers’, no wider than 6’4” (1.93 metres).

The dreadful accident happened as dusk was falling on Monday 26th July in the year of our Lord 1887, as the last boat of the day, the Usk, was slipping gently into Hadley Park Lock. The locks on the Trench arm, just south of Wappenshall Junction, were unusual as the bottom gates had a guillotine mechanism with the gates going up and down with a counterweight box, rather than swinging side to side. The top gates were the usual ‘mitre’ arrangement. They looked like something from the French revolution.

George Benbow was skipper of the Usk with thirteen-year-old, William Evanson as his crew and it appears that as the boat passed under the lock gate, George did not duck and was hit and killed by the counterweight box.

William later said at the inquest into George’s death,

“We were coming through Hadley Park Lock, and George shouted to me to drop the gate. I was by the horse at the time, but I ran to do as requested. As I lowered the gate George did not stoop at all and so caught his head against the weight box. George then got onto the cabin and cried ‘murder, murder’. I asked him what was wrong, but he did not speak again, and it was then that I saw the blood coming from his ears and he dropped down on top of the cabin.”

The Lockkeeper, John Chilton looked after the locks south of Wappenshall also gave testimony,

“I was following the Usk as she was the last boat of the day, and I needed to see that the locks were left in the right position. I was close to the boat when the accident happened and saw that George was looking behind to see how the boat was coming on – he ought to have stooped but instead he stood straight up and as the gate was lowered I heard a strange noise and the boy said, ‘He’s hurt, he’s bleeding’, and I asked George to lie down but he fell onto the deck and died within ten minutes – before assistance came.”

From that very day, the Usk was doomed, an unlucky, haunted boat that many boatmen would not work aboard, so she was sold and traded on the smaller canals on the Shropshire Union system, but the luck did not improve so she was finally abandoned and sank on the Montgomery canal near Crickheath, probably in the early 1890s, and there she lies to this very day, a ghostly reminder of a tragedy long ago.

The Usk and George Benbow may have long since sunk beneath the earth, but it is fascinating that restoring the Montgomery canal has given us a glimpse into the past and allowed this story to re-surface so that George, and his ghostly boat, the Usk, can be remembered.

‘Ghost Boat’ notes and research by Sue Ball & Jan Johnstone

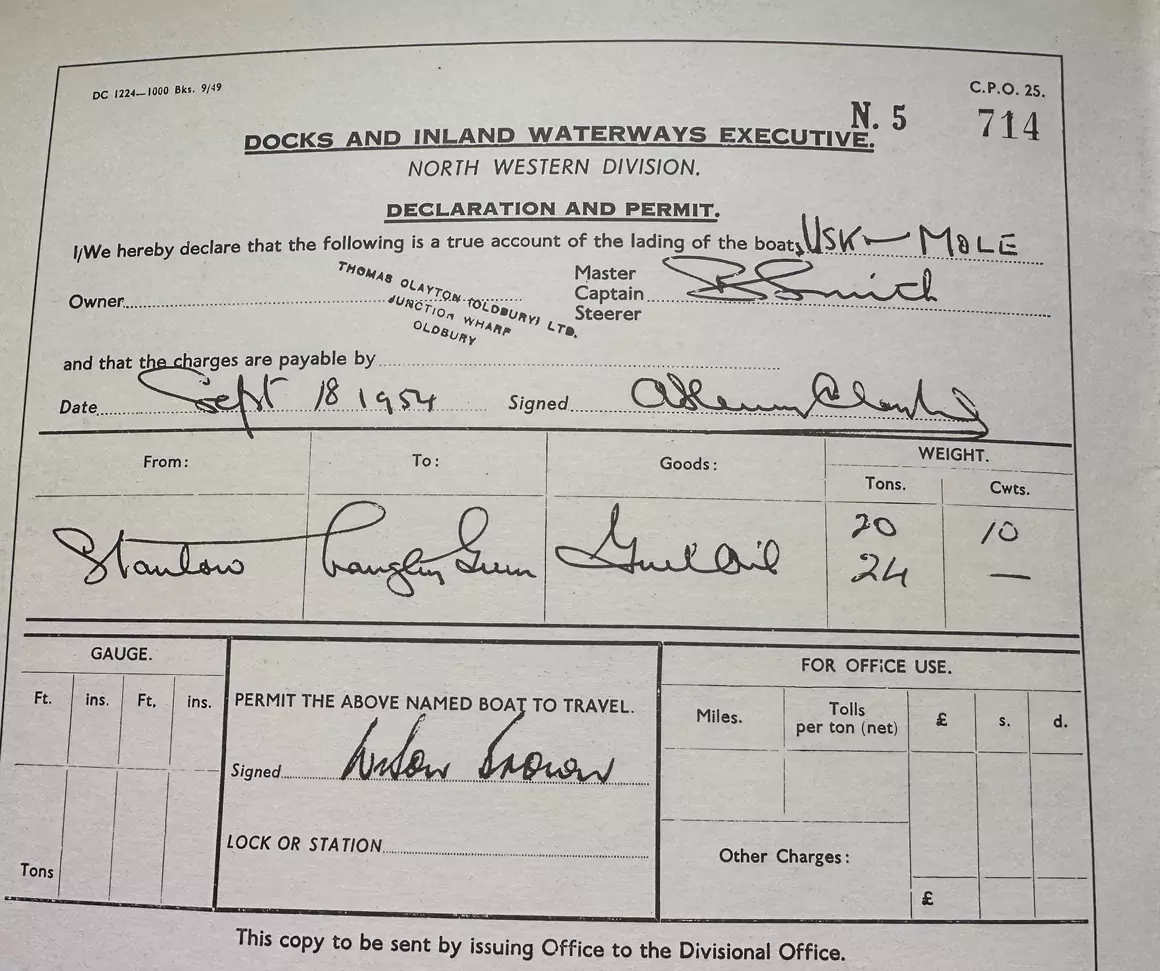

Thomas Clayton (Oldbury) Ltd, one of the most well-known of the canal carrying fleets, ran narrowboats widely over the entire network but especially over those in the northwest of England. Nicknamed ‘the tar boats’ they were immediately recognisable, not only for their holds covered by boards level with the gunwales, but also for their high standards and immediately recognisable paintwork, lettering and design on cabins and hulls.

Father William first established the carrying company in 1842 at West Drayton, Middlesex but had moved to a base at Salford Bridge, Birmingham, by the late 1840s. Initially carrying paving stones, drainpipes and timber, steady growth led to a further move to Saltley, on the Birmingham & Warwick Junction Canal, by 1862.

Around Saltley were several canal side gasworks; Adderley (now known as Camp Hill) 1844; Saltley 1858; Nechells 1881. Thus there emerged a high demand for coal, and for tar and other waste products to be taken away. By 1863 William was carrying tar to London as well as around the BCN and further afield, and ‘gas water,’ rich in ammonia, to burgeoning chemical industries engaged in fertilizer production. Initially, these were carried in barrels but, at this point, William began experimenting by converting some boats to ‘liquid carriers’, sectioning the hold into two or three compartments and covering with rigid planking. In time Claytons served virtually all gasworks which had reasonable canal access both delivering coal and removing the by-products of gas production.

William died in 1882 aged 73 and son Thomas assumed control.

Although part of ‘Claytons’ was transferred to Fellows Morton & Co in 1889, forming that other well-known carrying company, Fellows, Morton & Clayton, Thomas Clayton retained the 31 liquid carriers as well as other narrow boats and moved to his new base at Oldbury.

Claytons had begun naming their boats after rivers as early as 1853, the first one being Wye. This practice continued with only a few exceptions throughout. As boats were replaced in the fleet their names were regularly re-used, sometimes with the same fleet number as well. The fleet was also entirely horse drawn until 1937.

As far as the Shropshire canals are concerned there are references to Clayton boats collecting tar from Shrewsbury Gas works for carriage back to Oldbury, taking creosote from Oldbury to Cefn Mawr on the Welsh Branch and being regular visitors until 1927 – although reporting that the canals were already in poor condition by then.

Thomas Clayton (Oldbury) Limited Fleet List (1) shows two narrowboats named Usk:

Usk Fleet No 7 Joined fleet 09.1903 Registered Birmingham 1143 built FMC Uxbridge

Usk Fleet No 94 Joined fleet 01 1939 Registered Oldbury 6 built FMC Uxbridge

(Motorboat)

Clearly neither of these is our ‘Usk.’ And yet the boat newly built in 1903 was possibly a replacement for a previous Usk, this being Clayton’s usual practice. If so, what had happened to the previous Usk?

It could have been scrapped or sold on?

At the time of our accident George Salmon, boatman, was identified as the owner or, at least, operator of the ‘accident’ boat. He was not with the boat /crew on the day of the accident otherwise he would have been called to give evidence at the inquest. We have found no further trace of George Salmon.

If our boat was a Clayton boat and was sold on prior to the accident it appears to have kept its Clayton name. Would this have been allowed?

Conversely, if it wasn’t a Clayton Boat is it unusual it has a name that fits the Clayton profile and was operating on canals that Claytons were also operating on? The ‘accident’ boat was returning from Ellesmere Port via the SU main line and the Shrewsbury & Newport Canal. Ellesmere Port was a recipient of many waterborne goods, not least those destined for the developing chemical industries along the Mersey/Weaver. What had the boat carried to Ellesmere Port? What was it carrying back to Shropshire? The SU in particular was a busy route between Birmingham and Ellesmere Port. Presumably there would not/could not have been two boats with the same name operating over largely the same route? Or could there?

Had George Salmon purchased this boat or was he simply a small operator, leasing boats under contract to Claytons?

Or…?

Hadley Lock, Trench Arm of the Shrewsbury Canal

The locks on the Shrewsbury Canal were unlike most of the other locks on the canal network.

They were longer than usual, at 81ft long, and were also narrower at just 6ft 7ins wide, being designed to take four ‘tub boats’ at a time. Tub boats were the small, 3 ton wooden boats, less than 20ft long, 6ft 4in wide with a draught of 1ft 6ins that were standard on the canal system of the East Shropshire coalfield.

In addition, whilst the top gates of the Shrewsbury Canal were of the conventional swing type, the bottom gates of the locks were of the ‘guillotine’ type, vertical lifting gates. These were operated by counterbalancing a suspended central weight, a wooden box full of stones, attached to chains running round a horizontal wooden axle supported on the gate frame.

*It is this counterbalance weight/box that George Benbow struck his head on.

The Trench Arm runs from the Wappenshall Junction on the Shrewsbury & Newport Canal to Trench. There, an inclined plane was built to connect with the coalfield canals 75ft above. Inclined planes were fairly numerous on the Shropshire coalfield canals but they were of the ‘small’ variety. Narrowboats could not use these inclined planes. Thus tub boats brought their loads of coal to the head of the incline and were despatched down to the narrowboats waiting below for onward transit either to Shrewsbury or elsewhere on the national canal network.

It is clear our narrowboat, Usk, was heading to Trench to load with coal.

But narrowboats navigating the Trench Arm would have to be narrower than ‘normal’ narrowboats to pass through the locks on the arm. At other times tub boats would journey to Wappenshall for transhipment of cargo there. The Shropshire Union Railway and Canal Co had about 24 of these ay one point. (2)

So, given that it was navigating the Trench Arm, was our ‘accident’ boat a SUR&CC boat?

Also, as there was no winding (turning) capacity at the bottom of Trench Inclined Plane narrowboats had to make the journey there from Wappenshall helm first.

Jack Roberts on the Usk

Born in 1894 (3) Jack spent his working boat life on the canals of Shropshire, with an especial fondness for the Montgomery Canal. His memory was absolutely phenomenal and, with encouragement from family and friends, he committed his recollections to paper in 1960, eventually being published in 2015, long after Jack’s death in 1972.

Describing his first trip to Newtown with his father, aged 10 (so 1904?), Jack refers to a boat sunk just beyond the limestone wharf at Crickheath. “…practically a skeleton but you could see the name, the knees and the helm.” Jack names it as the Usk. Thus, there is a definite identification, primary evidence.

Jack confirms boats that went to Trench were ‘…seventy feet long but having only a six-foot-wide beam and a very low cabin’ and that boats going down to Trench went helm first.

His further comments about Usk, ‘…loading at the Gas Works (Shrewsbury) was a Thomas Clayton Boat, The Usk, a tank boat loading coal…) definitely identify a Clayton’s tank boat, probably Fleet No 7, built September 1903 (see above). Again, ’…Usk was worked by husband and wife Harry and Polly who had no family.’ As Jack was predominantly writing about boating experiences 1904 to 1921 this coincides exactly with the era in which wives and families joined husbands as crew and narrowboats became family homes in an effort to make canal carrying more competitive. Contrast this with the time of the ‘accident’ when boat crews were largely male.

In 1969 on an SUCS walk from Frankton to Crickheath Jack was still telling the same story!

The 2009 Dig

Tony Lewery (yes, he of ‘Narrow Boat Painting’) was called in when WRG volunteers unearthed the remains of a boat at Crickheath Wharf in 2009. Tony clearly knew of Jack Roberts and his autobiography – well he would, being so immersed in canals for so many years – although it had not yet been printed/published. He also clearly used it as the basis of his interpretation of the remains unearthed at Crickheath. Ironwork details apart he came to the conclusion that the imprint left ‘… was certain that it was a very round sided boat as many of the SU fly boats were’ but that it was impossible to measure the width.

Thus, there is no primary evidence that this boat could have navigated up to Trench. But there’s no evidence it couldn’t either?

Erm, would simply add – would an SU fly boat have been carrying coal? My understanding is, fly boats carried high value/priority delivery goods. Doubt coal would have been in this category?

After the accident

At some time after the accident the boat was sold to Thomas Moody, of the Moody family, canal carriers in Ellesmere who used it to trade coal from Black Park Colliery, Chirk, through to Newtown. At what point this happened is not known.

Like most of us, boat people would have been very sensitive to tragedy happening and then being required to go on working where it had happened. The likelihood is the boat would have been used in the normal way for a while but distaste would have built up and crews could have become increasingly reluctant to work it. Jack Roberts says ‘After the tragedy no SU boatman would work on the Usk…’ It must have reached the point where the owner considered the only possible solution was to sell the boat on. Jack Roberts comments ‘…it was afterwards considered to be jinxed.’

Was this George Salmon who sold it on to the Moodys because he couldn’t get the crews?

Was it Thomas Clayton or the SUR&CCC who could no longer get men to work it?

Did the Moodys find the same aura clung to the boat where tragedy had happened?

Finally, Jack tells us ‘After a few years and the worse for wear, it was placed to sink at Crickheath and the remains are still there.’

Or they were…

Sources:

- Thomas Clayton (Oldbury) Ltd: Fleet List. Alan Faulkner 2006 Narrow Boat Inland Waterways Heritage Magazine

- Canals of Shropshire: Richard K Morriss 1991 Shropshire Books

- Shropshire Union Fly-boats: Jack Roberts Autobiography 2015

Without doubt – we believe:

- On Monday 26 July 1887 nb Usk was travelling from Wappenshall towards, ‘the Trench’ on the Shrewsbury Canal. No idea of cargo? But at this point in history several inferences can be deduced?

- From Wappenshall the locks are climbing.

- The boat had travelled from Ellesmere Port and was heading toward ‘the Trench’, uphill in lock terms.

- The boats going along the Trench Arm, ‘have to navigate in reverse’ as there is no room to wind at the end of the arm – which is the base of the Trench Inclined Plane.

- It was towards the end of the day –‘it was light enough for him to see.’ Inquest July 1887.

- The lock keeper, John Chilton, was following the boat, ‘as it was the last one and he needed to see the locks were right.

- The guillotine gate (ie the bottom gate) into Hadley Park Lock had been raised. George Benbow, in charge of the boat, was ‘looking behind him, to see how the boat was coming on.’

- The guillotine gate was counterbalanced by a ‘box, full of stones.’ This hung lower than the gate.

- Boatmen knew (by experience?) to duck to get into the lock. On this occasion George Benbow did not do this: ’Deceased did not stoop at all and in consequence caught his head against the box. The deceased was looking behind him to see how the boat was coming on. He ought to have stooped but instead stood straight up.’

George Benbow was not decapitated. He did not hit his head on a bridge. Or any other folk tale.

He simply forgot to duck. A momentary lapse of concentration, remembrance.

Who, amongst us, has not been guilty of that.

Most of us survive. He, sadly, did not.

We have visited his burial site, said a prayer and blessed him.

We hope he rests in peace.

We surmise the boat was abandoned sometime twixt 1890 – 1900, probably earlier in the decade, given Jack Roberts description of the remains in 1904ish.