![]()

A longer story for you, this month. Because on 29 November 1894, Thomas Richards was executed in Carmarthen Gaol for the murder of his sister-in-law Mary Davies in Borth, near Aberystwyth. It is a reminder, should you need it, that in any act of murder, there are no winners; everyone loses. Here a woman was murdered and a man executed for to the benefit of absolutely no one at all. Apart perhaps for Mrs Richards, as you will see.

It was a simple story, and the mental contortions and gymnastics that Richards employed as he desperately tried to create an alibi, did no more than emphasise his guilt. In the end, the best he could say was that he didn’t mean to do it. The best the Aberystwyth Observer could come up with was that ‘However wicked the man may have been in this matter, it is but right that he should have a fair trial.’ But everyone knew he was going to be hanged.

It was a crime that shocked the small windswept town of Borth, north of Aberystwyth.

This peaceful retreat is troubled by the outside world only for a few months in the summer, when people of the most retiring disposition visit it for the sake of its bracing air and splendid sands. Borth contains a thousand inhabitants. These are largely composed of homely sea-going folk, who sleep in peace with open doors, and whose community of interest makes them unusually sympathetic with one another in sorrow and in joy. There was, therefore, no need for the constant tramp of the watchman.

Suddenly, their belief in the peaceful security of their homes was shattered and, most alarmingly perhaps, not by an outsider but by one of their own.

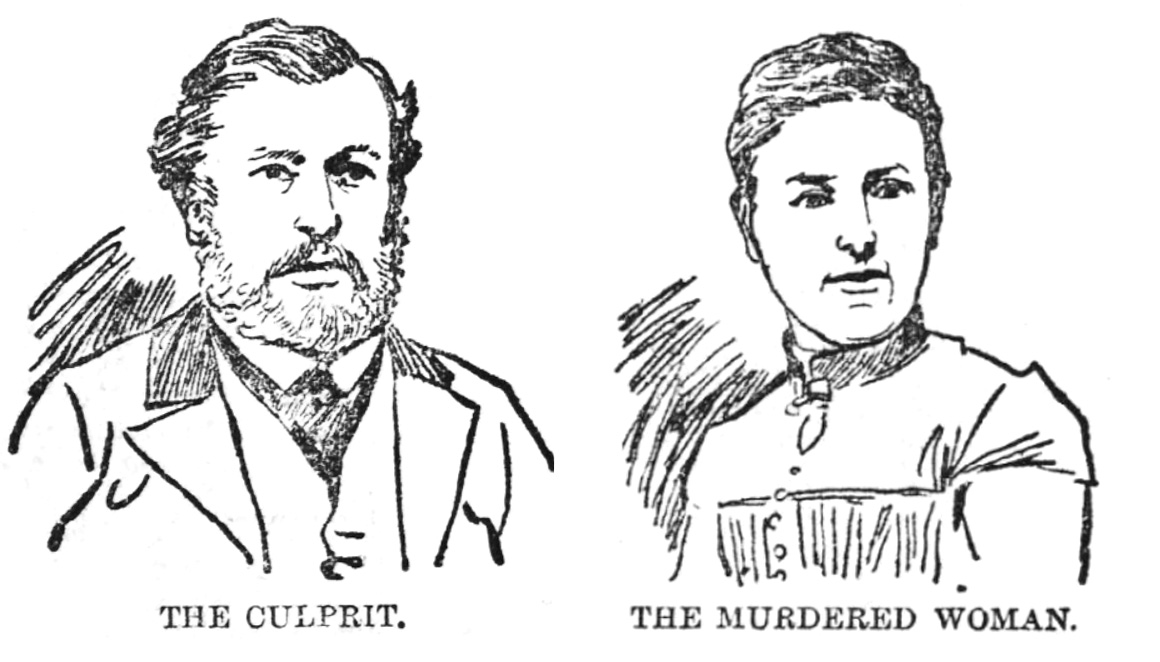

The South Wales Daily News devoted a whole page to the case, on 30 November 1894, and from this we get some impression of the pointlessness of the crime and some idea of the characters of those involved. The simple line drawings, helpfully provided, flesh out the names of the main protagonists. The paper is quite clear, too, about the origin of the crime. It was very simple. It was all about money. Nothing more complicated than that.

Mary Davies lived in what had once been the family home at 1 London Place in Borth. She was married to James, a sailor; they had no children. The house had been inherited jointly from their widowed mother by Mary and her older sister, Catherine. She had moved out when she married Thomas Richards, also a sailor, and together they had three children, two sons aged 15 and 13 and an 11 year old daughter. However, in February 1894, things became a little complicated.

The older boy, David, was in service, whilst the younger one lodged with his aunt, Mary Davies. Mrs Richards and her daughter were lodging in Llanelly. When Richards, who was working on the ss Electra, returned from a voyage to Llanelly to see his wife, he received a message saying that the younger son had been involved in an accident. This wasn’t entirely true. Any injuries he had sustained were slight and he was perfectly well, but it seems that Mary had had enough of looking after him and clearly felt that his presence was interfering with her work as a dressmaker. The boy was handed back to his parents.

Richards was very unhappy about this, since it brought an unwanted complication to his life, and the press were sure that this persuaded him look for revenge, either by stealing her money or, perhaps, by taking possession of the house where his wife had once lived.

Catherine had to return to Borth to a small cottage called Sandon Villa and her husband quietly waited for his chance – which came quite unexpectedly. In September 1894, when the Electra sailed into Swansea, he met his brother-in-law, James, who was sailing out to Bilbao in Spain. It must have seemed to Richards that this was the perfect opportunity; one he could not afford to miss. He asked his captain for four days leave so that he could receive medical treatment at Swansea Infirmary for a leg injury,, which was granted when a substitute sailor was found.

Richards then took a train for Aberystwyth. He made no attempt to disguise himself but after a drink in the Commercial Inn, he avoided others as much as he could and went out into the country, north towards Borth, stealing a pony from a field which he later abandoned. On arrival, he went to the rear of his sister-in-law’s and broke into the house through a door which he had helped to install. He knew his way around and went upstairs to Mary’s bedroom, where he knew she kept the keys to her chest of drawers where her savings were secured.

Mary must have heard something, for she woke, lit a candle and then screamed. Richards pushed her back on to the bed, grabbed a pillow and smothered her until she was still. Then he pulled her wedding ring from her finger. He opened the curtains at the window so that anyone who looked at the house in the morning would think all was normal, and then stole whatever of value he could find in the chest of drawers. He stole a £5 bank note and the details of a deposit account in the National Provincial Bank at Aberystwyth.

He made himself some tea, had breakfast and left the house through at the front door. Next, he slipped the £5 note under the door of his own house, Sandon Villa, before returning to Aberystwyth, and lodged for a few days at the Royal Oak Inn in Princess-street, where he repeatedly treated other guests to drinks.

He went to the bank and claimed to be Mary’s husband, James Davies, signing papers to that effect and then withdrew the interest from the deposit account – a little under £63. He took a new deposit note for the original £200, which he didn’t touch.

He then posted the deposit note back to Mary and posted Catherine £40 in gold sovereigns in an old cigar box. The landlady at the Royal Oak helped him by adding the addresses. Since her handwriting was neater than his.

Richards then, oddly, bought items of jewellery at Mr Truscott’s in Aberystwyth. At no point did he try to hide, and walked confidently around the town throughout the weekend, though his repeated attempts to sell what he claimed to be his wedding ring, following the assumed death of his wife, seemed to be a little strange. He left Aberystwyth for Llanelly on Monday morning.

Back in Borth, just nine miles away, Mary was found dead in bed by concerned neighbours on Saturday afternoon. Initially there was no thought of foul play. She was not only known to be asthmatic but also was suspected of eating skate, a fish was not regarded as wholesome and which was often thrown away by local fishermen. But suspicion started to grow. The curtains had not been opened with their customary care – they were bunched and untidy, the bed was a mess too, but perhaps she had had a seizure.

A pillow was lying over her head, her face and arms were discoloured, and the bed clothes were under and about the body in such a way as to indicate that there had been a violent struggle for life.

Catherine Richards came to the house grieve the death of her sister but it was only when the undertaker’s assistant noticed the missing wedding ring that suspicions began to grow. It was soon reported by a neighbour that Thomas Richards had been seen in Aberystwyth, though he hadn’t been seen in Borth, his home. His son David had obviously found the £5 that had been pushed under the door, though he didn’t know what it was, since he had never seen one before. And then that box containing 40 sovereigns was delivered to Sandon Villa by the postman. Catherine hoped desperately that it was a surreptitious way on the part of her sister of giving her a share in the cottage. But it was clear that she was clutching at straws. The deposit note had also been delivered to Mary’s home. The bank clerk remembered clearly dealing with James Davies – but of course it couldn’t have been him, because he was on his way to Bilbao. Inevitably, a description of Thomas Richards was quickly circulated to Welsh police forces.

Age 42 he looks, however, older. He has a pale complexion, dark brown hair, a full beard, and is getting bald-headed. He is slightly pockmarked, has a long scar on the forehead, is round- shouldered—in fact, almost hump-backed—and has broken a leg above the knee, thus rendering one limb stiffer than the other and producing a little lameness.

In Llanelly, a drunken Richards tried to sell the wedding ring to a man called Peake, first for 32s. Then for 15s, and finally for 2s 6d, but his mother would not lend him the money. Richards went then to Neath, where he was detained the following day in the Falcon Inn.

He denied everything – his identity, his movements, his involvement. He hadn’t been in Borth for over a year, he said. But once he was handed over to the Aberystwyth police, his inadequate alibis and lies began to crumble. He admitted to parts of the events but not to them all.

Yes, he had been in the house. Yes, he had put a pillow over Mary’s face, but he hadn’t intended to kill her, I only wanted to stop her from screaming. I did not know she was dead until you told me at Neath. He had been drunk and he didn’t know what he was doing. The wedding ring was a damning detail though, and he knew it. He said that he found it on top of the chest of drawers but no one believed him.

Scarcely anyone who knew the deceased woman believed there was the slightest truth in what the prisoner had said, because she, like many another countrywoman, was most particular about always wearing her wedding ring.

His continual protestations of innocence were feeble.

He was committed to the County Assizes, in Carmarthen on charges of murder, burglary, theft, and robbery. A fairly comprehensive indictment and one that could lead in one direction only. After he heard his death sentence, set for 29 November 1894, he commented to his solicitor that he thought the Judge was a bit hard on me. In his final confession, the day before his death, he admitted he was guilty of burglary and theft but emphatically denied taking the ring from Mary’s finger or murdering her. I am innocent of any intention of doing her any harm. He blamed everything on drink – and on a fever he had contracted off the coast of Africa which had addled his mind.

But Mary was dead, and as the Aberystwyth Observer noted, as he was led to his execution, the prison bell was tolling in cracked, unmusical tones a sad requiem for the dead.

Thomas Richards was buried within the walls of Carmarthen gaol and hymns were sung for him in Borth where, the newspaper observes, he received so ephemeral an impression of his moral responsibilities.

But there remains a terrible, macabre, irony here, of course. For the horrified and grief-stricken Catherine Jenkins, came into possession of the house at London Place and now makes it her abode, a place where her sister, Mary Davies, had been murdered by her husband.