![]()

No matter how inconvenient it might seem, climate change is for real. Those of us who are old enough can remember how things used to be and are ready to compare them with how things are now. Go back even further and the differences are even more stark.

To illustrate that particular point, let’s go back to January 1867 when it snowed; when it snowed bad.

At the start of the month, everything was fine; it had been a quiet start to the New Year. The Cardiff and Merthyr Guardian reflected that:

‘Christmas came to us in sunshine, and departed in storm. During his stay no frost crystallized the ground, no snow covered the fields, the hedges, and the trees. The inclemency of the weather has indeed been of the most uncomfortable kind. To the great annoyance of thousands of people, wind and rain revelled for three or four days over and around Cardiff with provoking persistence. But the tempests have gone and the season is singularly mild.’

There was some disappointment around, it seems, for the people were grieving for the white Christmas which would have brought something sparkling and other-worldly to their days.

Indeed, on 2 January The Flintshire Observer provided an explanation for them. It was the change in the calendar in the eighteenth century that had put paid to a white Christmas. The alteration, by moving the calendar along by eleven days, meant that the cold weather would always now arrive on 5 January. That is when you can expect ‘snow-laden trees and robins reduced by hunger and cold to an unnatural state of tameness.’ Well, we don’t know the name of our correspondent but he was almost on the button. Heavy snow started in the week, but the real problems came almost as predicted on 5 January. The drama some had been craving, blew in with remarkable violence.

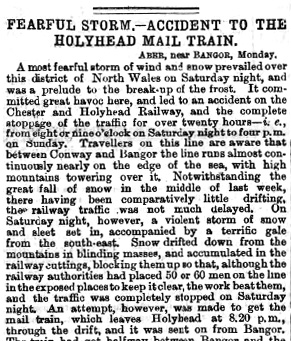

There was a ‘most fearful storm’ of wind and snow along the whole of the west coast, and especially in the north, where it ‘committed great havoc near Bangor,’ by causing an accident on the Chester and Holyhead Railway, and stopping all railway traffic for over twenty hours.

It began on Saturday night, with a violent storm of snow and sleet. The snow ‘drifted down in blinding masses,’ and blocked the railway between Conwy and Bangor, where the line runs between mountains and the sea. Over fifty men were sent out to keep it clear but the job was too great, and the line was soon completely blocked. They tried to get the Irish mail train to push through to Holyhead, using two engines, but halfway to Bangor, the wind was so strong that the post-office carriage was blown over. The men inside were shaken but survived. However, the engine couplings snapped, and the engines ploughed on together, until they were stuck in snow that was eight feet deep. The passenger carriages left the rails, but at least they did not turn over, though many of the passengers were injured. A relief engine was sent, but it too was stuck in the snow, unable to move either forwards or back. The guard had to run back to Bangor with a warning, but the telegraph lines were down, so it was impossible to stop any other trains. Visibility was so poor that signal lights could not be seen and there were a number of collisions. One train was standing in Aber station when another ran into the back of it, shaking and bruising the passengers.

Although men laboured through a bitter night, little progress was made and another 300 men, from Bangor were called out to clear away the snow. It was not until Sunday evening that one line of rails had been cleared and it was only on Monday afternoon that both lines were finally open.

‘The storm was fearful. At Aber, the gale drifted the snow in masses, blinding everybody exposed to it, and the railway officials were frequently thrown down by the violence of the wind as it rushed down the valleys.’

At one point, the storm increased to hurricane force, beating vicious, icy pellets into frightened faces. Snow was blown from the roofs of houses on to the streets in huge drifts, and men and women were blown to the ground. Several casualties occurred in Bangor, and the roofs of one or two houses disappeared into the distance. In the Penrhyn Estate there was significant damage to specimen trees; over sixty of them were blown down and uprooted. The roads were blocked too, with people needing to be dug out. It was the sudden visitation of catastrophe, although it occurs to me that their reliance upon men and their physical labour made it a simpler job to clear snow away than our own enthusiasm for machines to scrape and blow.

In the south things were not much better. The oldest inhabitants in these parts have never witnessed so severe a snow-storm as that which visited this locality on Saturday night last. There were similar issues with trains when one became stuck at Tregaron, south of Aberystwyth. It was caught in a drift that crossed the line near Tregaron Bog and, notwithstanding all the efforts of the driver and the might of his engine, it failed to negotiate the drift and there it remained till Sunday morning.

The wind blew the snow into drifts so large they made the roads completely impassable in all directions, so that those who had carts and horses on the road had to abandon them wherever it was safe for they were unable to proceed home with them as usual. The storm did not pass off without adding to its many other disasters, the loss of human life.

This is a sad reference to David Evans, a shoemaker, from Llanbadarn Odwyn, a place well known for being rather cold and bleak. He left home to sell shoes at Ysbyty Ystwyth Mineworks, and when returning at night was overtaken by the snow-storm and so perished.

Today we can look at all this and think about how climate change has turned all that snow into rain. But as we know too well, that brings its own problems.