![]()

It was all Hitler’s fault really. He invaded Poland in September 1939, the month of my conception. (Bet Hitler did not expect that!) A few months later, after my birth, my Dad packed Mum, Marylyn and Christine, my two sisters, and me into his Austin car and settled us at our maternal grandparents’ home in Llanon on the Welsh coast a few miles south of Aberystwyth. Dad then joined the Welsh Guards as a Chaplain having made a temporary departure from his Cheshire parish. He attended a short training session at Chester College then was posted to North Africa to keep an eye on Bernard Montgomery, possibly. We were to remain with our grandparents until late 1945.

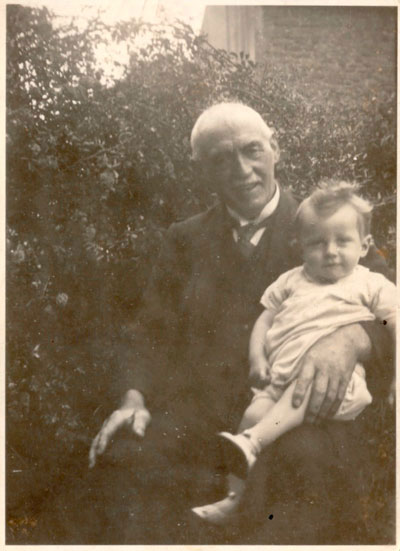

Our grandparents’ home was busy as they, a profoundly deaf aunt and we four newcomers suddenly filled the fairly large terraced house. Being one of an established large family Mum had a number of siblings who visited during their brief wartime breaks and, in a small, Welsh-speaking village, we were surrounded by numerous relatives and close friends. Grandfather, Capt. J D Jenkins a retired Master Mariner, churchwarden and one of the leaders of that community was an excellent gardener, tobacco grower, woodworker, keeper of bees and hens, fisherman and shooter whose contribution to the Ration Book was substantial: he was the Great Provider.

We village children had the run of the village as there was little danger. The main coast road, seldom used, ran through the village. Occasional troops passed through and, if they were American, we kids had learned to yell “Any gum, chum!” which was rewarded sometimes. There were very few strangers about: just the occasional tramp and a gypsy selling heather and simple clothes pegs. The village had a number of small farms surrounding it but most fields were for dairy cattle. Horses were used on farms and for road transport.

We children were always up for exciting entertainment. We climbed on gates and walls sometimes to watch a team of village men rope a horse for its castration. The busy smithy was always a place to watch horses being shod and wheels being rebuilt. Most adults seemed to work all the time and Mondays were always dominated by the need to wash and dry laundry: heavy work and very time-consuming as all textiles then were made of cotton or wool which took ages to dry. Domestic equipment was sparse: no fridge, phone, washing machine, clothes drier, vacuum cleaner, central heating and no bathroom. We tended to bathe weekly in the kitchen in a tin bath with water heated on the fire or kitchen range. There was one cold water tap available. Electricity had been installed a few years previously. Our long drop toilet was a stone shed some distance down the garden. My grandfather had built a “two seater” arrangement with a child and adult wooden seat side by side which I very much enjoyed. It’s always nice to be by your Mum when important things are happening!

By far, the worst day of the week for us children was Sunday. Noise, play and enjoyment were totally out of order. Adults, it appeared, had a conspiracy to ensure that lively children were kept utterly bored. Church attendance started the day with ‘Sunday best’ being required. We were harangued from the pulpit by a vicar who, following Welsh tradition, delivered his sermon in the singy-songy fashion of the day concentrating, it seemed, on ‘sin’ pretty heavily: he was really strong on ‘sin’. What were those adults up to? Did the vicar get his fair share of ‘sin’ one wonders?

After Church we had to visit a house in the village in which three maiden aunts were stored. They had to inspect, question and give us advice. One aunt decided that I had “Bishop’s Legs” which I found an interesting but mystifying pronouncement. Everything in our house had to stop for The News on the wireless, a routine which I enjoyed momentarily as the wireless had a green light, like a magic eye, which was revealed as the wireless warmed up. The content of the News went over my head though.

One of the local traditions enjoyed by children was ‘calennig’ which involved visiting village houses on New Year’s morning to beg for copper coin as a gift. Most adults would try to acquire new, shiny copper coin, farthings, ha’pennies or pennies as gifts. One other way of getting cash was to hold a rope across a lane to impede a marriage to demand that the groom paused his pony and trap to give us children a small handful of copper coin. There was little in the village available for children to buy, though.

We attended the village primary school; an old stone building overlooking the community. My grandfather had attended that school though he retired from formal education at the age of ten as he could read, write and do basic arithmetic. My mother’s generation attended there also. One dreadful feature was that pupils then were required to speak English only. The use of Welsh was frowned on and, probably, punished: a colonial remnant. Corporal punishment was routine and, on one occasion, my mother was hit so hard that her ear drum burst. My school days were pretty brief though I, a four year old, remember being tied with string to my iron-framed desk by Miss Jones as I had discovered that my sisters, in the ‘big class’, were having a much more interesting time than me. We were paperless even in those days, as our writing was all done on slates. The inkwells remained unused.

A feature of village life was the development of concerts in the Church Room which were a welcome home event for the returning-home-on-Ieave men and women who were in the Services. My Mum, a musician, and her pals would plan entertainment for the concert involving us children mostly who would sing and recite suitable material. The concerts always ended with Jim-the taxi singing (In English) his star item “Bless This House”: always popular. When the village knew that someone would be returning on leave many houses would hang a welcome-home flag from their upstairs windows.

Five retired Master Mariners found permanent anchorage in the village and kept watch over the whole of Cardigan Bay from a lookout high above the village while we children played with the black and white spotters’ cards displaying outline images of German military aircraft. The village offered little adult occupational opportunity: farming, seafaring, the church/chapel and school teaching seemed to be the chief available adult careers. Educational standards were very high. Public exam results were published in newspaper: and for many village children a good education would encourage an escape from local, rather poorly-paid jobs with limited occupational opportunity.

At the northern edge of the village a prisoner of war camp had been built during WW1 to house Italian POWs. This facility was resurrected in the early 1940s to provide accommodation for a number of Ukrainian refugee families who tended to keep to their own company. Yet, at Christmas time, they arranged a fine seasonal Party for the village children. The highlight of that event was men dancing on the cleared tables wearing their high boots doing the arms – folded style of dance. We found this hugely entertaining as our own boot wearing rules were totally different: simply marvellous! There were other evacuated children in the village from England, some staying with village relatives but others staying with unknown people. It was many years before I realised that we were ‘vacuees’ too. We were just locals, we had always thought.

Like most children we were given domestic jobs to do. Marylyn and Christine complained at times that they had far more jobs to do than me though preparing vegetables would have topped the list. I did enjoy cutting out the ribs from huge tobacco leaves, placing them on numerous bamboo sticks to hang around the house then drenching the dried leaves in a homemade gooey mix of molasses and other stuff before making tobacco ‘plugs’ for later consumption. My favourite job was spinning the honeycombs at great speed in the extractor. The faster, the better. When newspaper was available we children had to cut up the sheets into suitable sizes, impale each sheet on a special nail ready for toilet use. We boys had a special joke: “Who is the tallest man in the world?” Answer: “The man who wipes his bottom on the Evening Star!”

Food obviously was very important. I had two favourite meals: tatw stwmp (mashed potato and milk) and baked apples which, in our case had a unique feature as each apple was delicately flavoured with creosote: each shelf in the apple store was painted with that preservative. Salt was used extensively to preserve foods. Such was my dislike of salt that I have never used the stuff since childhood.

Towards the end of 1945 my Dad was demobilised. We children knew little of his wartime experiences apart from being located in North Africa (8th Army) then in Italy. Many years later we discovered that he had written to the parents of several deceased soldiers telling then something of their son’s life and death. Several parents responded thankfully to him. One letter stands out: Dad had written to a New Zealand vicar and his wife telling them that their second son had died. He knew that another son had been killed previously. We were able to lodge the parents’ letters in the Welsh Guards museum near Oswestry. Dad had also shown considerable pastoral support for some Italian POWs at some point. They had made him a simple, solid brass cross to accompany his portable Communion set which he used for the rest of his ministry.

Dad did return to the UK on leave at times though he never came to see us children. The decision was made that Mum would travel to Aldershot to be with him as cross-country travel was, at times, difficult and very time-consuming. In the meantime Mum took photographs of us children which she could send by post to him to keep him up-to-date with us.

Dad returned to his family though I, as a five year old, had never met him previously. The Austin was reawakened from its wartime hibernation and my family returned to our previously bomb – damaged vicarage in Ashley, Cheshire. I was carried from car to house being fast asleep but soon was delighted to discover an indoor bathroom and keen to find out how its unfamiliar equipment worked. Our home was a couple of miles west of RAF Ringway aerodrome (now Manchester Airport). A novelty to us was that a number of pasture fields were planted with upright telegraph poles set to deter airborne invasion and from our house we could see, in the mid-distance, active parachute trainees jumping from tethered balloons at Tatton Park in the immediate post—war years. For me those war years were wonderful: my sisters and I were well fed, well-loved and protected, being surrounded by many relatives and friends. What a staggering contrast to those millions of people for whom those times were utter, unending, man-made hell.

(A post-script. The week after my eighth birthday, in June 1948, the birth of the National Health Service took place. My parents’ delight at this development remains with me as The Most Important event following the War. Its value to us all could not be overstated.)

Author: Marytn Lloyd

Image credit: For the images of Llanon we must thank Dylan Jones proprietor of the White Swan in Llanon. The images are obviously not Dylan’s but he is the custodian of them. For more information about present day Llanon go to www.aboutllanon.co.uk